THIS ARTICLE/PRESS RELEASE IS PAID FOR AND PRESENTED BY the Institute of Marine Research - read more

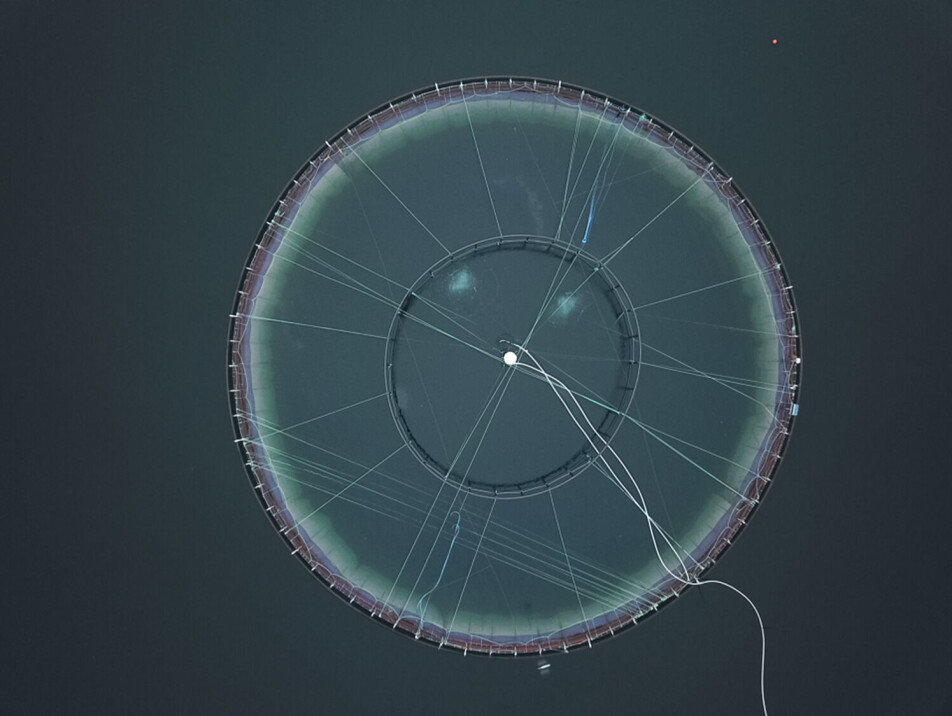

Researchers halved the amount of salmon lice at a fish farm

They combined off-the-shelf products with a new, dynamic strategy: Moving the salmon down – and up – away from the lice.

The researchers found 62 per cent fewer salmon lice on the fish in the experimental cages compared to the control cages.

Research was conducted over the period from when the salmon entered the marine cages as smolts until they were slaughtered two years later.

Changed the strategy in real time

“Previous tests have combined the same tools we used, but with the aim of steering the salmon away from the surface layer, based on the assumption that there are always most lice there,” researcher Tina Oldham explains. “That strategy has given mixed results because local environmental conditions can alter which water layer contains most lice. Salinity plays a key role in where we find most lice."

Oldham and her colleagues used an array of readily available tools: lice skirts, underwater lights and feed pipes that can be raised or lowered in the water, as well as a feed designed to strengthen their immune systems.

Fresh water at the surface pushes lice down

By monitoring salinity of the water in real time, the aim was to keep the salmon away from the lice by avoiding the so-called ‘halocline’.

“A halocline is a transition between water layers with an abrupt change in salinity. The salmon lice avoid low salinity waters and aggregate at this kind of transition,” Oldham says.

It is during periods with lots of fresh water at the surface that you get a halocline just below– a sudden transition to the saltier water.

Removed the lice skirt

The new measure taken by the researchers during these periods was crucial.

“A lice skirt is a barrier that prevents water flow through the upper metres of the cage. Normally, when lice are in the surface, that is sensible. But, in periods with lots of fresh water, the aeration required to maintain good water quality within the skirt actually pushes lice up into the barrier,” Oldham says. “Instead, because the lice shy away from fresh water, we actually want that to flow into the cage."

The researchers therefore removed the lice skirt during these periods. Meanwhile, they moved the underwater lights and feed pipes up to the surface to encourage the salmon to swim above the 'louse layer'.

This was done for three separate periods during production.

Salmon were encouraged into deeper waters

Normally, salinity levels are more evenly distributed. At those times, the researchers encourage the salmon into deeper waters where there are generally fewer lice.

The lice skirt was kept in place to protect any salmon that chose to stay near the surface, as well as salmon swimming up to fill their swim bladders with air.

The success of the measures meant 25 per cent fewer delousings were required. Specifically, there were 8 delousing operations required in the control cages compared with 6 in the experimental cages.

“Everyone wants to reduce the number of delousing operations,” Oldham says.

Delousing is stressful

Delousing costs money, but it is also associated with a certain amount of risk. Chemical delousing can have undesirable impacts on wild species in the surrounding area.

Greater use of delousing with mechanical and thermal (hot water bath) methods is more stressful for the fish and larger numbers of fish are dying than in the past.

Things going wrong during operations in cages, including delousings, is also one reason why farmed fish manage to escape.

Larger scale interventions may have a greater impact

The goal of the new method was to show what is possible with affordable off-the-shelf equipment.

“This can be adapted and installed on any existing farm. Our method worked well in three cages. At a larger scale, you may also get a cascading effect by lowering the infection pressure in the local area, in turn generating fewer lice,” Tina Oldham says.

She believes that they could have achieved better results if they had taken temperature into account as well as salinity.

“Sometimes the best temperature conditions were deep while we were trying to attract the fish to the surface. What happened in those situations, was that the fish swam back and forth through the ‘louse layer’ too many times. We are currently testing a version 2.0 of our method which tries to avoid that,” she concludes.

Reference:

Oldham et al. Environmentally responsive parasite prevention halves salmon louse burden in commercial marine cages, Aquaculture, vol. 563, 2023. DOI: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2022.738902

This article/press release is paid for and presented by the Institute of Marine Research

This content is created by the Institute of Marine Research's communication staff, who use this platform to communicate science and share results from research with the public. The Institute of Marine Research is one of more than 80 owners of ScienceNorway.no. Read more here.

See more content from the Institute of Marine Research:

-

Do whales compete with fishermen?

-

These whales have summer jobs as ocean fertilisers

-

Have researchers found the world’s first bamboo coral reef?

-

Herring suffered collective memory loss and forgot about their spawning ground

-

Researchers found 1,580 different bacteria in Bergen's sewage. They are all resistant to antibiotics

-

For the first time, marine researchers have remotely controlled an unmanned vessel from the control room in Bergen