THIS CONTENT IS BROUGHT TO YOU BY the Institute of Marine Research - read more

On the search for a specific parasite, researchers stumbled upon a fish-liquefying parasite instead

Kudoa has previously not been documented in Norwegian whitefish.

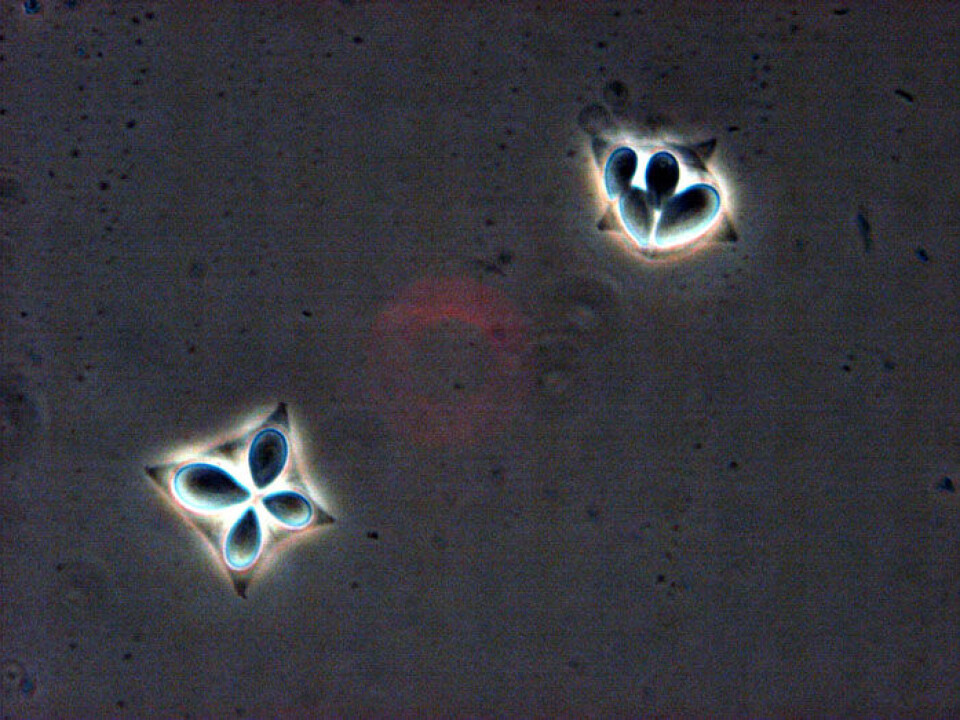

The mysterious parasite Kudoa thyrsites causes fish fillets to become so soft they could be consumed with a straw 24 hours after the fish's death.

It is not harmful to humans, but it can ruin a meal and perhaps the dinner guest's relationship with seafood. Documented findings of Kudoa in Norway have been limited to mackerel. Until now.

Searched for one parasite, but found another

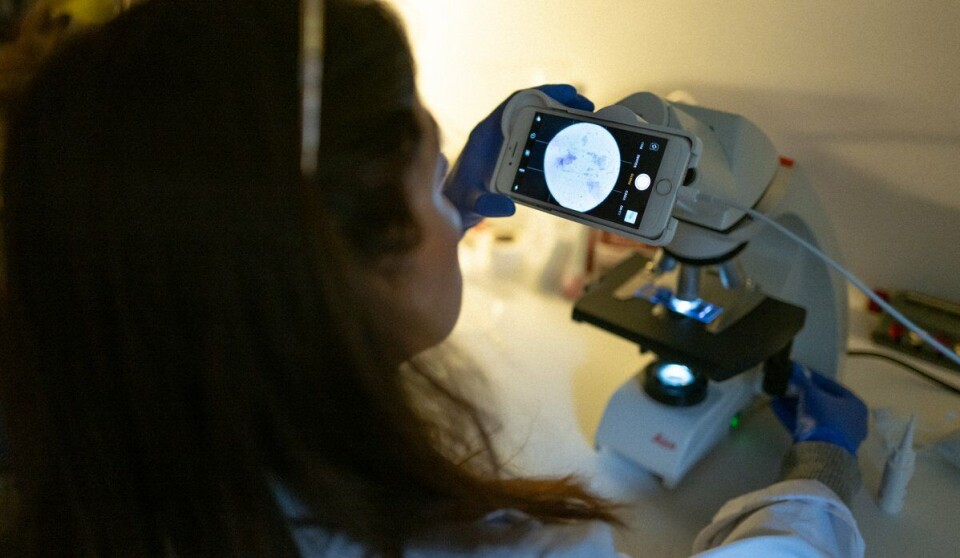

“I was actually looking for anisakis, which is my main research focus, but I noticed that my tweezers sank straight into the tusk fillet without resistance. Closer inspection under the microscope revealed the presence of Kudoa spores that had begun to digest the fish,” researcher Paolo Cipriani at the Institute of Marine Research (IMR) says.

It was thus completely by chance that the parasitologist found the Kudoa parasite in a tusk from central Norway.

A DNA test confirmed the finding as Kudoa thyrsites, which has never before been documented in Norwegian whitefish.

Not uncommon in mackerel

“In our annual screening of commercially caught mackerel, we find Kudoa in one to three out of a hundred fish,” research colleague and Kudoa expert Lucilla Giulietti says.

Researchers believed the parasite was something mackerel carried from the southern areas of the Atlantic Ocean, and that it did not actually reside in Norwegian waters.

But Giulietti has also recently found Kudoa in juvenile mackerel, born and raised in Norway.

“The more we look for Kudoa, the more we find it,” she says.

May indicate that the parasite is also 'Norwegian'

“The findings in juvenile mackerel and the new jelly tusk from Trøndelag may indicate that there are actually local Kudoa infections, and that the parasite is already established in Norway," Giulietti continues.

Researchers do not know the life cycle of the parasite and do not know how it is transmitted between individuals.

"The key to understanding the transmission and potential spread of Kudoa is to understand how the fish get infected and where the parasite goes from there,” she says.

It is an important target for further research on the mysterious parasite, especially now that climate and ecosystems are changing rapidly.

Caused trouble in Canadian salmon dinners

“Outbreaks of the parasite have previously caused major problems for salmon farming on the Pacific side of Canada. Liquid fish flesh is something the Norwegian salmon industry probably does not want. It can be devastating for both food and reputation,” she says.

Since the enzymes from the parasite need one to two days to liquefy the flesh, the fish may become soft when they have already reached the market.

Relatively stable amounts of Kudoa in mackerel

IMR is not aware of cases in Norwegian farmed salmon so far, but Kudoa has not been monitored systematically in this fish either.

Instead, the 19 years-surveillance programme that IMR has conducted on mackerel shows that the occurrence in this fish has been relatively stable in samples from Norwegian commercial catches throughout the recent years.

It is the findings in these new locations and hosts that make researchers eager to learn more.

‘New’ fish can also host the jelly parasite

“Kudoa has also been reported in wild-caught pink salmon in the Pacific Ocean. It is also an interesting species to follow up as a potential host,” says Giulietti.

Pink salmon has become the dominant wild salmon species in Northern Norway every other year.

The possibility of spreading unknown disease is a possible risk associated with pink salmon, which is native to the Pacific.

This content is paid for and presented by the Institute of Marine Research

This content is created by the Institute of Marine Research's communication staff, who use this platform to communicate science and share results from research with the public. The Institute of Marine Research is one of more than 80 owners of ScienceNorway.no. Read more here.

More content from the Institute of Marine Research:

-

These whales have summer jobs as ocean fertilisers

-

Have researchers found the world’s first bamboo coral reef?

-

Herring suffered collective memory loss and forgot about their spawning ground

-

Researchers found 1,580 different bacteria in Bergen's sewage. They are all resistant to antibiotics

-

For the first time, marine researchers have remotely controlled an unmanned vessel from the control room in Bergen

-

New discovery: Cod can adjust to climate change – from one generation to the next