THIS CONTENT IS BROUGHT TO YOU BY NTNU Norwegian University of Science and Technology - read more

Rethinking recovery: How high-intensity interval training can aid heart attack patients

We all know that exercise is good for us, but how much, how hard, and for how long?

Ulrik Wisløff was convinced that the training techniques he had used helping Olympic athletes could help heart attack patients too.

He had seen how quickly cross-country skiers improved their cardiac fitness by training at high intensity for short intervals — an approach called high-intensity interval training.

When he started as a PhD candidate at the Faculty of Medicine in 1997, Wisløff asked his supervisors if this might be a good research project. At the time, cardiologists knew that it was good for heart attack patients to exercise, to improve their quality of life and possibly reduce the risk of additional heart attacks.

But the conventional wisdom in 1997 was to prescribe moderate exercise — not high intensity training. Nevertheless, Wisløff thought his idea made perfect sense.

His colleagues? Not so much.

“I asked the cardiologists, couldn’t we use the same principles as we do in athletes in heart failure patients? And they said yes, let’s do that. But you are crazy. You can’t do it in humans. You have to start in rats,” he says in NTNU's English language podcast 63 Degrees North.

From rats to humans

“I had never seen a rat. At least not a laboratory rat,” Wisløff says.

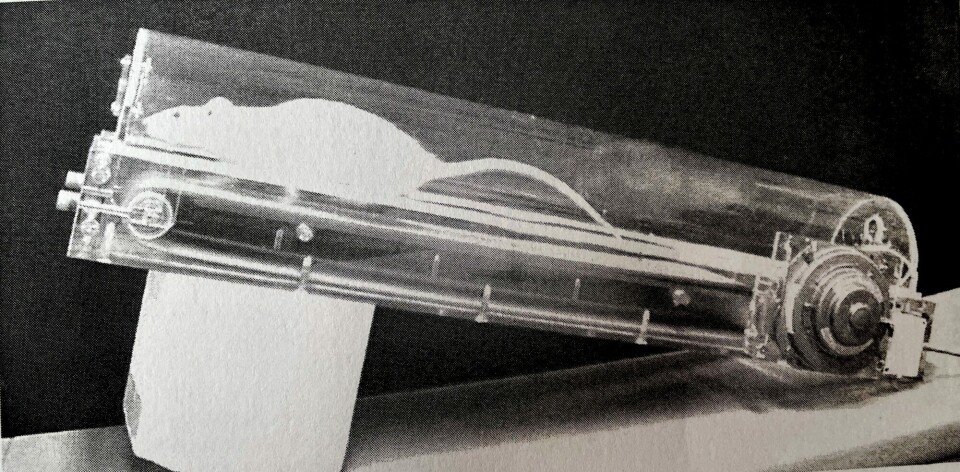

Soon he was busily building little treadmills, specially outfitted with equipment to allow him to measure the rats’ VO2 max, which is the maximum amount of oxygen a body can use during intense exercise. It is a standard measure of cardiovascular fitness.

The results were so promising he got approval to conduct trials in humans.

From heart attack patients to ageing well

Wisløff went on to study high intensity training in patients with heart failure. He recruited 27 patients whose average age was 75.

One-third of them did moderate training, one-third did high intensity training, and the last third served as the control group, and was just given the standard advice regarding physical activity.

The results were incontrovertible: High intensity training was best.

The paper he published in 2007 has been downloaded more than 105,000 times.

That success led Wisløff to explore other areas where high intensity interval training could make a difference — whether it was ageing well, or in his latest efforts, to see how it might help Alzheimer’s patients — but not the way you might think.

You can learn more about Wisløff’s journey in the podcast episode below.

References:

Rognmo et al. Cardiovascular Risk of High- Versus Moderate-Intensity Aerobic Exercise in Coronary Heart Disease Patients, Circulation, vol. 126, 2012. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.123117

Stensvold et al. Effect of exercise training for five years on all cause mortality in older adults—the Generation 100 study: randomised controlled trial, BMJ, 2020. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.m3485

Tari et al. Safety and efficacy of plasma transfusion from exercise-trained donors in patients with early Alzheimer’s disease: protocol for the ExPlas study, BMJ Open, vol. 12, 2022. DOI: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-056964

Tari et al. Temporal changes in cardiorespiratory fitness and risk of dementia incidence and mortality: a population-based prospective cohort study, Lancet Public Health, vol. 4, 2019. DOI: 10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30183-5

Wisløff et al. Intensity-controlled treadmill running in rats: VO(2 max) and cardiac hypertrophy, American Journal of Physiology Heart and Circulatory Physiology, vol. 280, 2001. DOI: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.3.H1301

Wisløff et al. Superior cardiovascular effect of aerobic interval training versus moderate continuous training in heart failure patients: a randomized study, Circulation, vol. 115, 2007. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.675041

More content from NTNU:

-

This determines whether your income level rises or falls

-

Why is nothing being done about the destruction of nature?“We hand over the data, but then it stops there"

-

Researchers now know more about why quick clay is so unstable

-

Many mothers do not show up for postnatal check-ups

-

This woman's grave from the Viking Age excites archaeologists

-

The EU recommended a new method for making smoked salmon. But what did Norwegians think about this?