THIS CONTENT IS BROUGHT TO YOU BY University of Oslo - read more

Why do children take things so literally?

It has been a mystery in children’s language development, but researchers are now closer to solving it.

“I love you so much I could eat you up,” a mother might say to her child.

Chances are the mother will be met with a confused and possibly concerned look. What does she actually mean?

To grasp this, the child needs to understand more than just the literal meaning of the words. They must understand the intentions behind them.

Researchers at the University of Oslo have investigated the ways in which children develop the ability to understand meanings and nuances beyond what is actually said.

“The big mystery is this: How can children be skilled at comprehending many complex linguistic tasks, yet interpret things completely literally in other situations?” says Ingrid Lossius Falkum.

She is a professor of linguistics and philosophy of communication at the University of Oslo.

A literal development phase

After many years of research into this puzzle in children’s language development, Falkum and her colleagues have come closer to an answer.

“We see that from around the age of four, children go through a developmental phase, a kind of literal phase, where they often take words at face value,” she explains.

Children can be quite strict during this phase, which typically lasts several years. They may be fixated on speaking correctly and choosing the ‘correct’ meaning of a word, often interpreting your words literally, even when it does not make sense.

“I'm surprised by how strong the tendency to interpret things literally is among many children,” Falkum says.

The researchers believe this prevents children from accepting expressions that have multiple meanings.

Such as the expression: 'John is a lion.' While an adult understands it as a compliment, meaning John is brave and strong, children in the literal phase might think you mean John is an animal.

Focused on ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ language

Preschool children are concerned with the idea that there are right and wrong ways to use words.

“Children are in a developmental phase where it's crucial for them to learn the meanings of words as agreed upon by the language community,” says Falkum.

This focus can make it difficult for them to go beyond the literal meaning to understand what the speaker meant.

“Literal meanings can be seen as the correct way to use a word. Children are keen on following the rules,” she says.

This literal phase does not stem from an inability to understand non-literal language, such as metaphors and irony.

“But the developmental phase often leads them to prefer clear and precise communication,” says Falkum.

Surprised by the findings

This challenges previous research on children and non-literal language use.

“There's been a long-standing hypothesis suggesting that children struggle with understanding non-literal language due to difficulties in adopting others’ perspectives,” Falkum explains.

But that's not actually the case. The ability to understand is there, but literal meanings seem to carry more weight.

“We notice that children remain rather rigid and prefer literal interpretations for many years, provided a literal option is available,” she says.

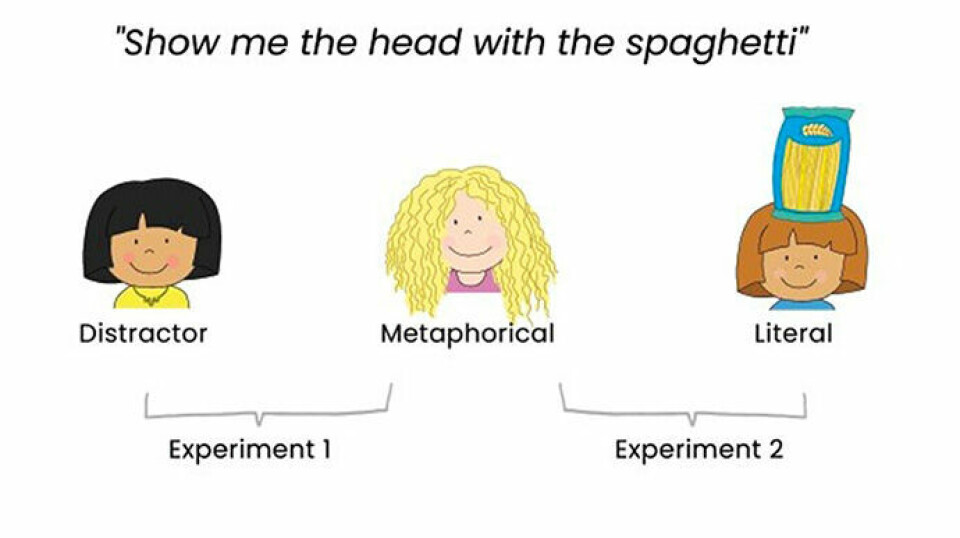

However, when no literal interpretation is available, children often select the meaning that best suits the context. This may be a metaphorical interpretation.

Differences between younger and older children

The researchers have tested more than 3,000 children to see how readily they accept alternative uses of words.

Take this sentence: 'Peppa Pig is in the basement.' The person is referring to the Peppa Pig book.

Five- and six-year-olds quickly interpret statements literally, even if it seems unusual for Peppa Pig to be in the basement. They justify this interpretation by reasoning that those were the exact words used by the researcher.

Interestingly, younger children seem to understand the non-literal meaning better than older children.

“Children who are a bit older start to wonder if there could be multiple meanings, and they opt for the safest one – the one aligning with what is literally said,” Falkum explains.

She notes that the authority of the adult researcher influences the situation. Since the adult said it in that particular way, the children believe they probably meant it literally.

Not all test subjects worked out

Falkum and her colleagues also tested adults in their research for comparison.

However, when they recruited a group of philosophers from the University of Oslo for irony studies, things did not go quite as expected:

“We had to stop because many philosophers interpreted the statements just as literally as the children did. It wasn’t due to a lack of understanding irony, but rather because they approached the task with a deeply philosophical mindset. Perhaps they believed someone was attempting to deceive them?” she says.

Researching language models

A central theme in all of Falkum’s research is how the ability to interpret others’ intentions develops.

She is currently investigating how humans communicate with artificial intelligence-based language models, compared to how we communicate with each other.

“We know little about the human aspect of this type of communication. The AI revolution was striking for us because suddenly it’s super relevant to have expertise in how human communication works,” she says.

That's why she believes knowledge is needed to train the machines, and to understand how communication with them affects us. Perhaps children also interpret language models literally?

“Initially, we examined how children learn to understand others’ intentions. Now we wonder how they can understand an entity without intentions they can reason about,” she says.

Understanding others’ intentions is a prerequisite for all communication. Therefore, in principle, we should not be able to understand the language produced by language models.

“We want to explore what happens when we attribute meaning and intentions to AI models regardless,” she says.

This content is paid for and presented by the University of Oslo

This content is created by the University of Oslo's communication staff, who use this platform to communicate science and share results from research with the public. The University of Oslo is one of more than 80 owners of ScienceNorway.no. Read more here.

More content from the University of Oslo:

-

Where humans outshine AI: “There's something hopeful in these findings”

-

Why we need a national space weather forecast

-

Mainland Europe’s largest glacier may be halved by 2100

-

AI makes fake news more credible

-

What do our brains learn from surprises?

-

"A photograph is not automatically either true or false. It's a rhetorical device"