THIS CONTENT IS BROUGHT TO YOU BY NTNU Norwegian University of Science and Technology - read more

Unlocking the secrets of Viking and medieval walrus tusk trade

For nearly 500 years, two small Scandinavian settlements survived in Greenland before mysteriously disappearing. What happened?

More than a thousand years ago, Norse traders sailed the dangerous waters of the North Atlantic in open boats. Their ships carried precious goods like walrus tusks and hides. These were bound for Norwegian coastal cities such as Trondheim and Bergen.

Many walrus ivory artefacts from this time have been found across Northwestern Europe. This shows that walrus ivory was a global commodity, according to James Barrett. He is a professor of medieval and environmental archaeology at NTNU University Museum.

“At the moment, the farthest south and east that there are discoveries of these skulls, from Greenland, is Novgorod and Kyiv,” he said on the latest episode of 63 Degrees North.

This expansive trade network made Barrett and his colleagues curious. Where did all the walrus ivory come from? It could have come from almost anywhere in the Arctic.

To find out, the researchers turned to advanced scientific tools to analyse ancient DNA.

And what they found shocked them.

Western Greenland was a major source

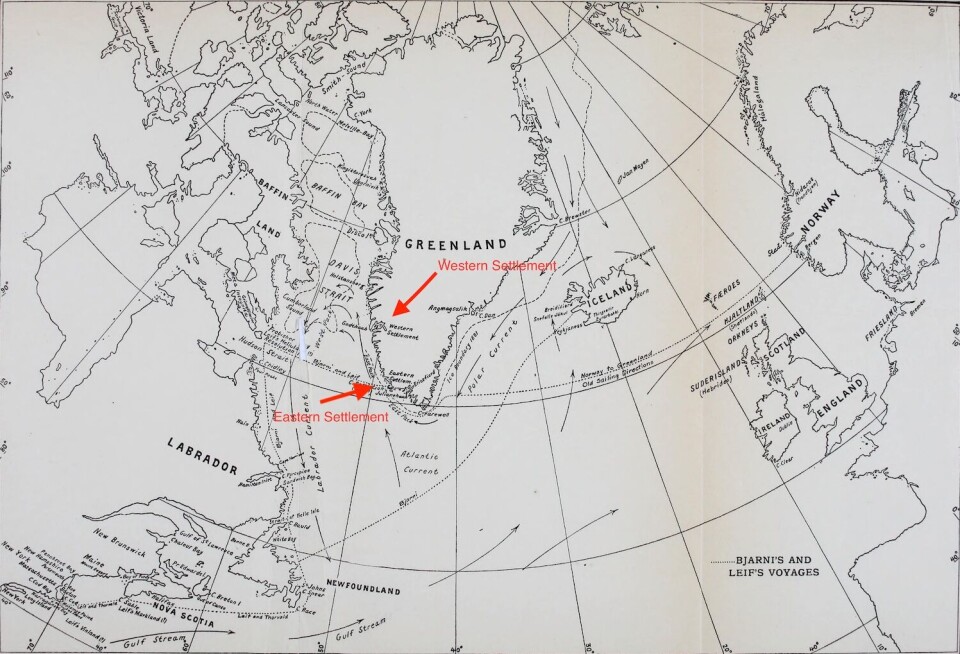

“The likelihood is that the whole of Eurasian demand during the Middle Ages was heavily focused on Western Greenland. That was quite a shock, because the assumption understandably in the past was that Eastern European finds of walrus ivory were probably coming from places like the White Sea and the Barents Sea,” said Barrett.

There were walruses in Iceland, once. But ancient DNA helped another team of researchers see that the Icelandic walrus population disappeared not long after the Vikings had arrived there in about 870 CE.

And the disappearance of walrus from Iceland was surely a factor in encouraging Vikings to head west to Greenland, according to Barrett.

“When the Vikings settled in Iceland, the walruses there disappeared very quickly. So they probably were over-hunted in Iceland. And that would be one of several variables that led to the settlement from Iceland of Greenland in the late 900s,” he said.

More importantly, it may have played a major role in why those settlements were eventually abandoned nearly 500 years later.

Farthest north to Inuit trade

As part of their research, the team looked at the sizes and characteristics of walrus skulls from this period. They also had information from analysing the ancient DNA.

“Through time, the walruses were getting smaller through the Middle Ages. In addition to that, they were of a genetic subgroup which was more common in the very far north, rather than more southerly areas in Western Greenland,” Barrett said.

“So the hypothesis is that the Norse were hunting the walruses and demand in Europe was very high, of course. And then gradually, they hunted them farther and farther north, and then they reached the farthest north one can go. In fact, they also began to trade for them with the Inuit,” he said.

In the 1200s and 1300s, medieval Scandinavian artefacts begin to show up at Inuit sites in the very far north of Northwestern Greenland and Ellesmere Island, according to Barrett.

“So putting it all together through time, they’re having to harvest smaller and you’re having to go farther north. And if you’re living in southwestern Greenland and you have to row or sail, and it’s a short season, then this is not a trivial issue. And eventually, the journey just became too long to be realistic,” he said.

And that is likely one of the reasons why Greenland’s Western Settlement was abandoned in the 1300s.

Church taxes and elephant ivory

Why did the Norse Greenlanders want to trade with Europe in the first place? It was a long and perilous journey, so the motivation had to be strong.

According to Barrett, it’s likely that the settlers just wanted to maintain contact with Europe. But there was a second reason – religion.

“A bishopric was established in Greenland in the early 1100s. And in 1153, an archbishopric was established here in Trondheim, in Nidaros, with the Greenland bishopric being part of that church province,” he said.

This connection came with obligations.

“There were economic transactions, including the payment of church tax, from the bishopric in Greenland to Trondheim. And that was paid in very large measure, in these early years, in walrus tusks,” said Barrett.

But eventually, two major changes led to the collapse of the walrus ivory trade.

The first was the arrival of elephant ivory in Europe in the mid-1200s. The second was a shift in artistic styles, from Romanesque to Gothic, and the way ivory carvers worked their craft.

Elephant tusks were bigger and longer than walrus tusks. This made them better suited for Gothic-style religious carvings, which tended to be more detailed and naturalistic than the earlier Romanesque style.

And yet, Barrett said, their research showed that the harvest of walrus tusks only intensified after the arrival of elephant ivory and the subsequent drop in value of walrus tusks.

This seems counterintuitive – at first.

“It does make sense, because if you’re in Greenland, you want to maintain your contact with Europe. And if the price per tusk has decreased, then rather than hunting fewer walruses, one actually has to hunt more. And so we see that the Greenlanders were caught up in quite complicated market dynamics, in what was a global commodity,” he said.

A look to the future

Now, Barrett and his colleagues have expanded their research on walruses and other marine creatures with an EU-funded project called 4-Oceans.

Researchers from across Norway and Europe are looking at a range of marine creatures, from cod to otters to whales – and yes, walruses – to understand their economic and social importance over the last 2000 years.

They are also using high-tech tools to make predictions about how a changing climate will affect these and other marine animals.

References:

Barrett et al. Ecological globalisation, serial depletion and the medieval trade of walrus rostra, Quaternary Science Reviews, 2020. DOI: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2019.106122

Barrett et al. Walruses on the Dnieper: new evidence for the intercontinental trade of Greenlandic ivory in the Middle Ages, Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Biological Sciences, 2022. DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2021.2773

Keighley et al. Disappearance of Icelandic Walruses Coincided with Norse Settlement, Molecular Biology and Evolution, vol. 36, 2019. DOI: 10.1093/molbev/msz196

More content from NTNU:

-

Why is nothing being done about the destruction of nature?“We hand over the data, but then it stops there"

-

Researchers now know more about why quick clay is so unstable

-

Many mothers do not show up for postnatal check-ups

-

This woman's grave from the Viking Age excites archaeologists

-

The EU recommended a new method for making smoked salmon. But what did Norwegians think about this?

-

Ragnhild is the first to receive new cancer treatment: "I hope I can live a little longer"