THIS CONTENT IS BROUGHT TO YOU BY NTNU Norwegian University of Science and Technology - read more

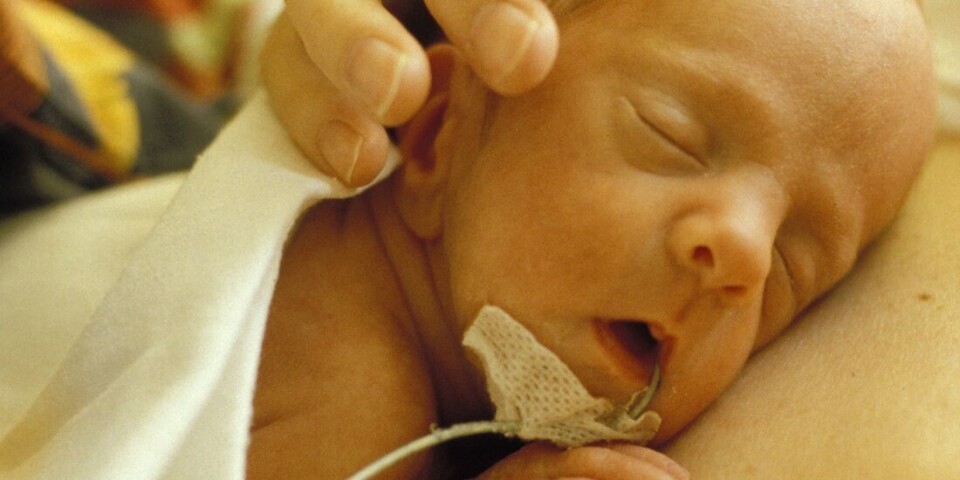

Premature babies should also have early skin-to-skin contact with their mothers

Researchers have found several benefits of early skin-to-skin contact between baby and mother.

More premature babies who had early skin-to-skin contact with their mother were being breastfed at the time of discharge from the hospital and up to one year later. But this is far from the only benefit.

A team from St. Olav’s Hospital and NTNU have looked at this issue in a number of articles. They now hope more hospitals will change their practice so that premature babies are not separated from their mother in the first few hours after birth.

“The first few hours after birth are an early sensitive period. During this period, the first contact between mother and child is established,” says Laila Kristoffersen.

She is an associate professor at NTNU's Department of Public Health and Nursing.

The research team has therefore investigated whether immediate skin-to-skin contact after birth for very premature babies and their mothers has an effect on the child’s development in both the short and long term.

Early skin-to-skin contact is standard practice for full-term babies

Healthy babies born after reaching full term are normally placed on their mother’s chest immediately after birth. Skin-to-skin contact between mother and baby helps strengthen bonding, promote breastfeeding, and reduce stress. But this practice has not been common for premature babies.

“Since premature babies often need medical care after birth, the standard practice is for them to be placed in an incubator and transferred to a neonatal intensive care unit,” says Kristoffersen.

This means that mother and baby can be separated for several hours, and in the worst cases several days, after birth.

From birth, premature babies are more vulnerable than full-term babies, as their brains and other organ systems are not fully developed. This makes it particularly important to facilitate early bonding and a gentle start to life, says Kristoffersen.

This is also in line with the latest WHO recommendations, which recommends immediate skin-to-skin contact for all premature babies.

In Norway, St. Olav's is one of very few hospitals to make such a practice possible. However, the researchers believe that skin-to-skin contact immediately after birth can safely be carried out for babies born as early as week 28 of pregnancy. A normal pregnancy lasts around 40 weeks.

More mothers breastfeed after early skin-to-skin contact

The research team has published a number of articles from the study. The latest, published in JAMA Network Open, finds a link between early skin-to-skin contact and breastfeeding.

“More mothers who had skin-to-skin contact with their baby after birth were breastfeeding at the time of discharge from the neonatal unit and for the first year of their baby’s life,” says Kristoffersen.

The research team looked at a total of 108 premature babies born between 8 and 12 weeks before full term.

In one group, babies had skin-to-skin contact with their mothers after birth, while the other group received the standard treatment, which involved being transferred to an incubator in a neonatal intensive care unit.

“Breastfeeding promotes the bond between mother and baby. It also protects against infections. Furthermore, breast milk contains vital nutrients, hormones, and enzymes, which we believe are particularly beneficial for premature babies. We therefore consider these findings to be a good reason to facilitate immediate skin-to-skin contact, even for very premature babies,” she says.

Long-term development

The researchers also examined the children's cognitive and motor development after a period of two to three years, but here they found no differences between the groups.

“It didn’t really surprise us that two hours of skin-to-skin contact after childbirth did not affect cognitive or motor development at two to three years of age," says Kristoffersen.

Many factors affect the development of premature babies.

“It takes a lot for interventions like this to have long-term consequences that can be measured using the tools we have,” she says.

In addition, all three neonatal units that were included in the study were good at facilitating early parent–premature baby interaction during the hospital stay.

“In this case, an intervention lasting two hours can only make a relatively small difference,” she says.

Safe and welcomed by mothers

“Researchers have previously shown that immediate skin-to-skin contact following premature birth is feasible and safe for both mother and child. This is also true in the case of births through caesarean section,” says Kristoffersen.

During the interviews, it also became apparent that the mothers themselves want close contact with their baby following a premature birth.

“The mothers said that having their baby on their chest after birth was important for early bonding and to promote a feeling of security and coping,” she says.

Kristoffersen explains that the positive effect of early skin-to-skin contact between mother and baby is accepted as a matter of course when a baby is born full term.

"There are good reasons why we should offer the same opportunity to vulnerable premature babies who we know are at greater risk of attachment problems and tend to face a variety of challenges relating to mental health and behaviour,” she says.

At St. Olav’s Hospital, they changed their routines back in 2007 and then made it possible for immediate skin-to-skin contact between mothers and premature babies from week 32 onwards (8 weeks before the due date).

Many years of experience at St. Olav's Hospital

“In 2014, we began the study where we have facilitated skin-to-skin contact for premature babies from as early as week 28 of pregnancy. These babies were born 12 weeks before their due date,” says Kristoffersen.

After the study was completed in 2020, immediate skin-to-skin contact became standard practice even for babies born as early as week 28 of pregnancy.

She says the staff is very experienced in handling babies who need medical treatment, such as simple respiratory support, after a premature birth.

“This can be done without any problems when the child is lying on the mother’s chest. In this way, we can ensure that premature babies and parents are also able to be together during that early sensitive period following birth," she says.

Kristoffersen and her colleagues hope the findings can help more people to see how important it is to change routines for when babies are born prematurely.

References:

Føreland et al. Postpartum Experiences of Early Skin-to-Skin Contact and the Traditional Separation Approach After a Very Preterm Birth: A Qualitative Study Among Mothers, Global Qualitative Nursing Research, 2022. DOI: 10.1177/23333936221097116

Kristoffersen et al. Immediate Skin-to-Skin Contact in Very Preterm Neonates and Early Childhood Neurodevelopment: A Randomized Clinical Trial, JAMA Network Open, vol. 8, 2025. DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2025.5467

Kristoffersen et al. Skin-to-Skin Care After Birth for Moderately Preterm Infants, Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing, 2016. DOI: 10.1016/j.jogn.2016.02.007

Kristoffersen et al. Skin-to-skin contact in the delivery room for very preterm infants: a randomised clinical trial, BMJ Paediatrics Open, vol. 7, 2023. DOI: 10.1136/bmjpo-2022-001831

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

More content from NTNU:

-

Why is nothing being done about the destruction of nature?“We hand over the data, but then it stops there"

-

Researchers now know more about why quick clay is so unstable

-

Many mothers do not show up for postnatal check-ups

-

This woman's grave from the Viking Age excites archaeologists

-

The EU recommended a new method for making smoked salmon. But what did Norwegians think about this?

-

Ragnhild is the first to receive new cancer treatment: "I hope I can live a little longer"