THIS CONTENT IS BROUGHT TO YOU BY SINTEF - read more

Could today's conservation requirements be the nail in the coffin for Svalbard's cultural heritage?

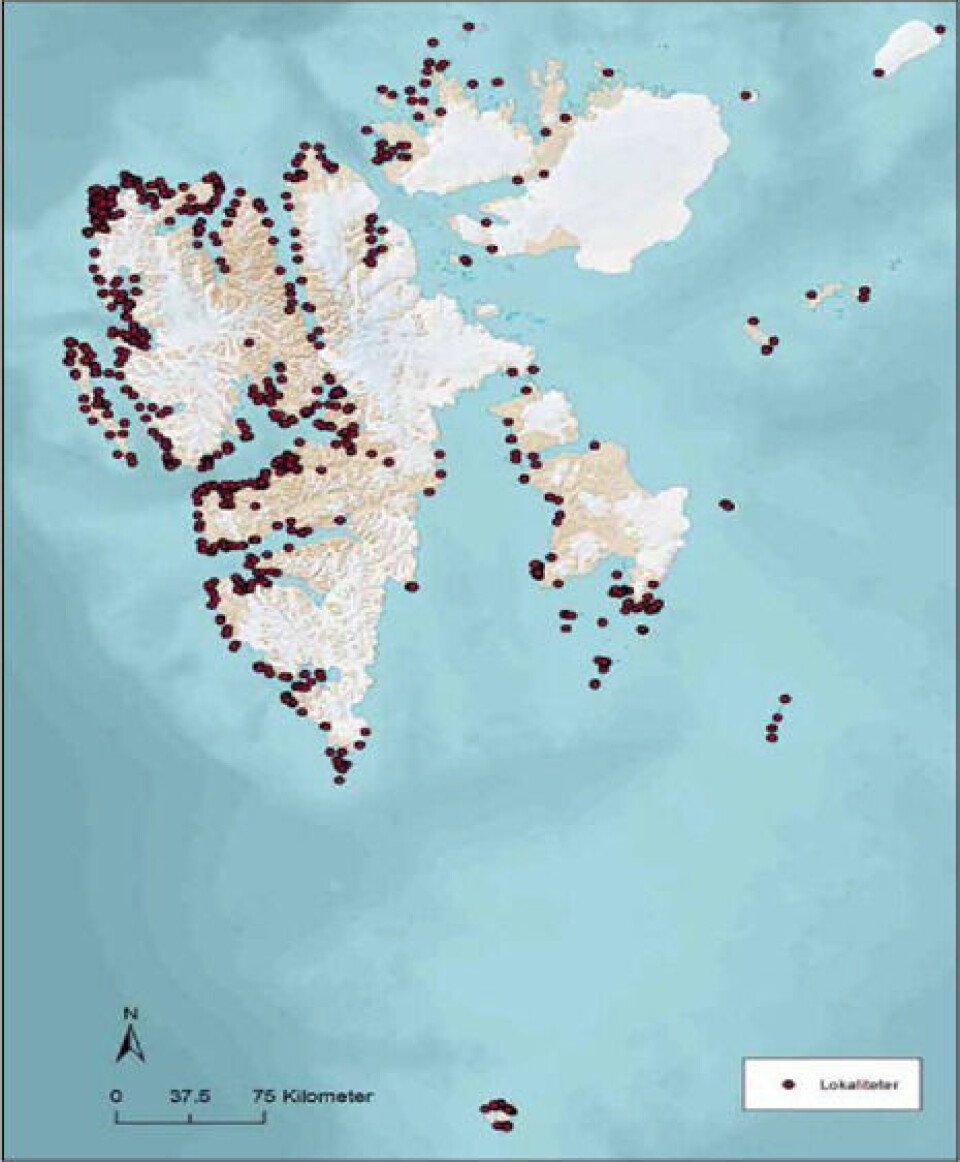

Rapid climate change in the Arctic is causing cultural heritage at Svalbard to weather. This may force new management practices.

The warming in Arctic regions is happening three times faster than the global average. This has major consequences for the unique cultural monuments at Svalbard.

The old cable car station and forge in the mining town of Hiorthhamn are among the cultural monuments that are in danger of being lost. They are weathering due to rapid coastal erosion, caused by accelerating climate change.

“Temporary security measures from 2021 show that the management practices in this case adapted in the face of the climatic challenges,” Ingalill Johansen Seljelv says.

She has taken her master's degree in cultural heritage management at NTNU, in collaboration with the research project PCCH-Arctic (Polar Climate and Cultural Heritage – Preservation and Restoration Management). Here, the researchers investigate issues concerning the conservation and restoration of cultural monuments in the Arctic in light of climate change.

Through fieldwork, observation, and analysis of documents, Seljelv has investigated how the owners of the cultural monuments and the management have handled conservation work in Longyearbyen and its surroundings in 2003–2022.

The forge was saved

Seljelv says that immediate measures at the forge were carried out a few days after permission had been granted. There was only a minimal delay due to a lack of personnel.

The proceedings were short, probably as a result of good and close cooperation early in the application process.

Temporary erosion protection at the cable car station was also carried out a few days after permission had been granted. In this case, the processing time was unusually short.

“This illustrates how the administration is able to handle an acute danger caused by climate change,” she says.

Management practice characterised by special conditions

The proceedings for measures on the cable car trestles, show how management practices on Svalbard over time have been characterised by several different conditions.

Owners must consider special factors when carrying out measures here. This involves aspects like financing, the permit's validity and terms, season, and logistics.

The mining company Store Norske was the custodian of the cultural heritage in the period examined. Responsibility now lies with the building conservation centre at Svalbard Museum on behalf of the state at the Ministry of Trade and Fisheries.

The measures have also, in many cases, been dependent on funding from Svalbard's environmental protection fund. The fund has two allocation rounds a year. The award is valid for three years. This gives time limits for carrying out measures. There are also restrictions on the season in which the measures can be carried out.

“If unforeseen events occur, you must wait until the next season. The validity of the permit decision sets the timeframe for the entire execution. If measures are not carried out before the decision becomes invalid, you can apply for an extended deadline if there are special reasons. If this is not the case, the permit will lapse. Then you must start the application process over again,” Seljelv explains.

The restrictions are ineffective and expensive. They can often worsen the condition of cultural monuments.

How should the practice be adapted?

Many of the documents that Ingalill Johansen Seljelv has examined, express a strong desire that the work on restoration must be made more efficient.

“Not only in terms of time use and finances, but also for climate reasons. Management practices on Svalbard should therefore be adapted considering climate change,” she says.

Such adaptation does not have to conflict with the regulations. On the contrary, it can be interpreted as being in line with both legislation, parliamentary reports, and the climate strategy of the Directorate for Cultural Heritage.

“I also believe that the wording in the decision on the preservation of the cable car facility can actually be used to allow new methods of maintenance and repair. It has previously conflicted with traditional management practices,” Seljelv says.

It may become necessary to use non-antiquarian methods

Climate change has had a major impact on the cable car facility and its management. Store Norske's first application for measures from 2013 was submitted after investigations showed that the condition had suddenly worsened. Probably because of a changed climate.

In the years after this, climate change continued to negatively affect the cable car trestles. Several applications for measures have mentioned changes in climate as a particularly important reason why they should be restored.

Will the cable car trestles remain in the future?

Climate change will continue to have a major impact on the management of the cable car facility in the future.

“If our aim is to preserve the overall cultural environment in Longyearbyen and its surroundings, it will be necessary to change the management practices. This can, for example, involve challenging the traditional practice by using non-antiquarian methods,” Seljelv says.

This may involve adopting new techniques for foundations and types of materials, among other things. There has not been a tradition of doing this at Svalbard before.

“In this way, it is more likely that we will be able to preserve more cultural monuments. The combination of special conditions on Svalbard and accelerating climate change make such a change necessary,” she says.

Continuing the restoration work under a traditional management practice is therefore difficult to carry out, both practically and financially. The researcher believes that it will hardly be possible to restore the cable car trestles in a way that preserves the entirety of the facility without making any interventions in the visual expression.

Entirety or authenticity?

There are, however, several arguments against such an adapted practice.

“Should the cultural monuments be preserved as they are, or should measures be taken that interfere with the cultural monuments? In such a discussion, one should question what one wants the overall principle for management in Svalbard to be,” Seljelv says.

It becomes a question of which is worse: That certain objects and thus the entirety of the facility are lost, or that cultural monuments are restored using what is considered less correct methods in an antiquarian perspective.

If preservation of the entirety is the most important, then the methods of restoration should be subordinate. If authenticity is the most important, the wholeness will be subordinate.

“Should the management of cultural heritage in Svalbard be practical or perfect? The answer is perhaps a bit of both – as perfect as practically possible,” Seljelv says.

Natural to do further research

Seljelv's investigations are part of a larger research project. It is therefore natural that further research on the topic is carried out, she thinks.

“Proposals for further research can, for example, be affiliated with the new building conservation centre under the auspices of Svalbard Museum,” she says.

The centre is currently responsible for managing the state-owned cultural heritage at Svalbard.

“It would be interesting to investigate how this transition takes place, and how the building conservation centre eventually chooses to manage these objects,” she says.

Seljelv also believes it could be of interest to look more closely at the cultural heritage administration's climate policy, both on the mainland and at Svalbard.

She herself believes that she has documented the beginning of what is most likely a shift in the management practice for cultural heritage in Svalbard.

Reference:

Seljelv, I.J. Praktisk eller perfekt? Kulturminner og klimaendringer på Svalbard. Forvaltningen av taubaneanlegget i Longyearbyen og omegn 2003–2022 (Practical or Perfect? Cultural Heritage and Climate Change in Svalbard. Management of the Cable Car System in Longyearbyen and Surroundings 2003–2022), Master's thesis at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU), 2023.

More content from SINTEF:

-

Saving seagrass and French oysters: New solutions give new life to Europe's coastal areas

-

What does ultra-processed food do to our gut flora?

-

This new device can make it cheaper to heat your home

-

Propellers that rotate in opposite directions can be good news for large ships

-

How Svalbard is becoming a living lab for marine restoration

-

New study: Even brand-new apartments in cities can have poor indoor air quality