THIS CONTENT IS BROUGHT TO YOU BY SINTEF - read more

School buildings affect students and teachers

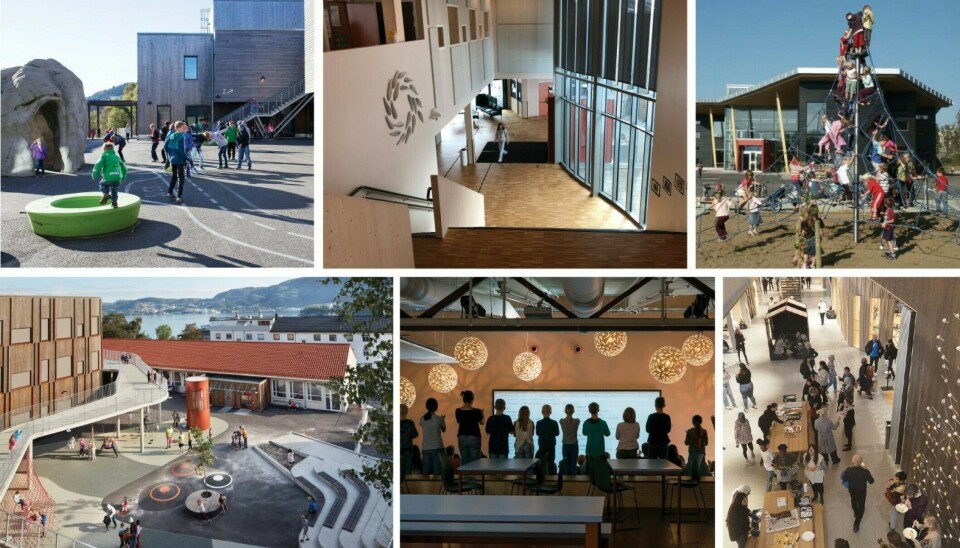

The interaction between architecture, pedagogy, and different forms of learning needs to be considered when planning new schools.

'The pupils and apprentices must develop knowledge, skills, and attitudes so that they can master their lives and can take part in working life and society. They must have the opportunity to be creative, committed, and inquisitive.'

This is one of several statements in the objective clause of Norway's Education Act.

But can the state and municipalities fulfill these ambitions?

Researchers in the project Tomorrow’s Schools have delved into how the physical environment of schools is used and experienced by different users.

They have also examined how user experiences align with the goals of the Education Act. The researchers have looked specifically at land use, floor plans, and light and sound conditions.

Some schools are good role models

The project identified model schools in the municipalities Tromsø, Trondheim, Bergen, and Nordre Follo that were considered good role models for school planning. The goal is to find solutions that can support better schools for the future.

Previous studies show that the school’s physical environment affects learning, teaching, and well-being for teachers and students. In other words, it is the qualities of the building that impact the pedagogy.

“The fields of pedagogy, architecture, and design have defined much of the current research on the physical environment of schools, but this research has been fragmented and not very interdisciplinary,” says Solvår Wågø, a research manager at SINTEF.

She therefore believes that pedagogy must be afforded a greater role when planning the schoold of tomorrow.

Evolving working methods require new solutions

Schools have undergone major changes.

Today, they focus more on interaction and activity, according to Wågø. This requires a different way of teaching and thus distinct spaces to teach in.

For example, different furniture is needed for a 6-year-old than for a 15-year-old or an adult.

“A lot of schools have chairs that force six-year-olds to sit with their legs dangling. A traditionally furnished classroom doesn’t provide choices for sitting in different ways. Some children solve tasks best while lying on the floor,” she says.

Various layouts – but what works?

A number of variations on open solutions, flexible layouts, home areas, and shared spaces with different room sizes have been tested. So far, it has been uncertain whether and how these different layouts have contributed to achieving the educational goals.

The researchers therefore conducted a systematic survey of recent findings in the field.

They also examined the learning environment at selected schools, including asking students and teachers about their experience of the physical school environment.

Users must be involved in the planning

The transition to new, flexible learning spaces and the expectations of new pedagogical practices can, however, be experienced as challenging for both students and teachers.

“Involving users is critical for success when implementing changes. Pupils and teachers need time to adjust to innovative school buildings,” says Wågø.

The importance of daylight

Previous research also shows a clear link between satisfactory daylight design and positive effects in schoolchildren, including less absenteeism and better academic performance.

“An international research project in the UK evaluated various design aspects, including air quality and temperature. Of all the considered aspects, light had the strongest individual effect on learning in children,” says Claudia Moscoso, a research manager at SINTEF.

On the other hand, research shows that poor window design is associated with high cortisol levels (stress), increasing nearsightedness, poorer mental health, and concentration issues in schoolchildren.

“This is particularly relevant in the Nordic countries, with long winter months that reduce our exposure to daylight,” says Moscoso.

Views provide a mental break

More daylight also means more views. Research shows that views, especially of nature, provide mental relief.

Connections have also been made between exposure to nature and improved cognitive functions and mental health in children and young people.

“Of the schools that were included in the study, Holen School has an attractive view of the fjord. Fagereng School looks out over green areas. In both cases, the view was considered mentally relaxing,” says Moscoso.

Social noise can hinder learning

An effective learning environment also requires good sound conditions. This means that students experience minimal noise disruption, can understand information, and maintain their concentration.

“Children’s hearing is not fully developed when they start school. They have to learn to interpret words and signals, as well as how to cope with noise. What you want pupils to hear therefore needs to have a significantly higher sound level than unwanted sound,” says senior research scientist Anders Homb.

The researchers examined the acoustics in rooms they expect will be most relevant in the years to come. This includes classrooms of 60-80 square metres. They also looked at larger rooms.

They found that mitigating social noise should be given more emphasis when planning teaching areas. Large open layouts and teaching environments over 100 square metres are generally unsuitable for communicating instructions unlesss sound-absorbing systems are installed.

“A lot of children are sensitive to acoustic conditions, which perhaps especially impact second-language learners, pupils with sensory difficulties, and language teaching in general,” says Homb.

Different pupils have different needs

According to Norway’s Education Act, all students have the right to a learning environment adapted to their needs.

Norwegian building codes largely addresses the needs of those with mobility, visual, and hearing impairments. But inclusion also means taking care of children who are sensitive to strong sensory input from light and sound.

Wågø says that knowing where you are, where you're going, feeling like you belong, feeling safe, and having the opportunity to find a sheltered place can be good for everyone when the world feels a bit big and incomprehensible. For some, it is absolutely essential.

The home area is the space that a class, group, or grade level has their 'home base’ at school. Interviews reveal that pupils, teachers, and management all experience their home area as a safe place to be.

Students at all the schools in the study use both locker areas and hallways as learning spaces. Many say they work best outside of the home area or classroom. As one pupil put it:

'We work on project work in the hallway, practice presentations in a corner, sit on the stairs, in the amphitheatre, and other places.'

This shows that there is a need for spaces where pupils can sit alone, in different ways and in different environments. Often, these are places that were not specifically planned as learning areas.

School as a hub in the local community

Wågø believes that good architectural design is a necessary tool to achieve important societal goals.

“The choice of solutions for buildings and outdoor spaces also affects the social sustainability of the local community. Architecture is a tool that can influence and enable new practices,” she says.

Informal and spontaneous use of schools and outdoor areas means that students and the local community feel a sense of ownership of the school facilities.

In the common areas at Holen School, pupils play table tennis and shuffleboard after school hours, and the music room is used by students who play in bands. In the afternoons and on weekends, the schoolyard is bustling with children playing.

“People boast about how great it is here,” says one of the teachers.

Useful for municipalities

The main goal of the research project has been to establish a knowledge-based foundation for the interaction between architecture, pedagogy, and learning. It is intended to be used in the planning of future school facilities.

Bergen municipality is in the middle of working on a new school use plan. It is the municipality’s most important document for planning school buildings and future school structures.

“So the recommendations in the report are particularly relevant for us,” says Lina Gaski, who heads policy plans for kindergartens and schools on Bergen’s city council.

Reference:

Wågø et al. Morgendagens skoler. Rom for læring, lek og utvikling (Tomorrow’s Schools. Space for learning, play, and development), SINTEF academic publishing house, 2024.

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

More content from SINTEF:

-

Saving seagrass and French oysters: New solutions give new life to Europe's coastal areas

-

What does ultra-processed food do to our gut flora?

-

This new device can make it cheaper to heat your home

-

Propellers that rotate in opposite directions can be good news for large ships

-

How Svalbard is becoming a living lab for marine restoration

-

New study: Even brand-new apartments in cities can have poor indoor air quality