THIS CONTENT IS BROUGHT TO YOU BY NTNU Norwegian University of Science and Technology - read more

New teaching method can bridge the gap in girls' and boys' reading abilities

In Norway, girls are much better at reading than boys. However, girls and boys perform equally well when using a new teaching method.

How well do children know letters and their corresponding sounds?

In Norway, the gender difference on these tasks when children start school is significant. The girls have a clear head start.

“We see these differences in all categories – for upper case and lower case letters, for the names of the letters, and for their corresponding sounds,” Hermundur Sigmundsson, a professor at NTNU’s Department of Psychology, says.

Girls’ letter-sound knowledge is clearly better than that of boys, and girls remain far better readers than boys at age 15.

Since reading is key for so many subjects, this has major consequences for many boys.

A new study published in Acta Psychology show that this discrepancy is not the case for first graders in Iceland.

Girls and boys are equally competent in Iceland

“We find no gender differences in letter-sound knowledge in Iceland when children start first grade,” Sigmundsson says.

This competence applies to reading skills in general, as well as the letters and sounds.

“We found that over 56 per cent of the children in Iceland had already cracked the reading code by the time they started school. This means that they could read certain words. There were no gender differences here either,” Sigmundsson says.

In Norway, only 11 per cent of children can read words when they start first grade. 70 per cent of these are girls.

So why is that?

Early focus in school

“When Icelandic children start school, the learning focus is on letters and their corresponding sounds,” Sigmundsson says.

Sigmundsson has argued for introducing this approach in Norway as well, where letters and sounds come before words.

In Norway, many children are instead encouraged to look at the whole word in context.

The assessment of letter knowledge used by the researchers to measure these skills was developed by Norwegian special education teacher Greta Storm Ofteland. The results obtained using this test have been published in five international articles so far.

Tested new method

The test results are also the basis for the new learning method called READ or LESTU, which has attracted international attention for its positive results through the Icelandic project Kveikjum neistann! (Ignite the spark!).

The researchers tested the new method with first graders in the 2021/2022 school year.

“After the first year in Iceland, everyone in our project had cracked the reading code. This is a very good starting point for further reading development, which focuses on reading comprehension, creative writing, and pronunciation,” Sigmundsson says.

The following year, 98 per cent of pupils had cracked the reading code, indicating that the result was not an isolated one.

Reading skills improve with individualised instructions

A major part of the method involves providing individualised instructions. The key is to acquire a baseline reading at the start of the first school year, and do follow-up measurements in January and May.

“The goal for our project in Iceland is for 80 to 90 per cent of the pupils to be able to read by the end of second grade. That translates to reading text and understanding it. We managed to hit that target with the children who started in first grade in autumn 2021. In second grade the following year, 83 per cent of these children could read text and understand it. We found no gender gap,” Sigmundsson says.

Iceland not necessarily the best

The project results – which showed that 56 per cent of the youngest pupils in Iceland had cracked the reading code – are due to the work that is done at home and in kindergarten before children start school.

Kindergartens in Iceland focus much more on learning letter sounds than in Norway.

But this isn’t necessarily only a good thing, according to Finnish professor Heikki Lyytinen.

“Lyytinen believes that kindergartens should emphasise physical activity, language and vocabulary development, and developing social skills," Sigmundsson says.

Children learn the names of the letters, but not their corresponding sounds in Finnish kindergartens. Finnish children first learn the letter-sounds at school when they are 7 years old.

Lyytinen says the letter names can be learned in the same way that children learn the names of other things, like animals.

And the Finns must be doing something right.

Finnish approach is best as children get older

While the Icelanders are very good at reading early in their schooling, they tend to gradually fall behind.

Finland leads the way in the Nordic states when children are 15 years old. This is the age that pupils take the international PISA test (Programme for International Student Assessment). Norway doesn’t rank very high at that age, either.

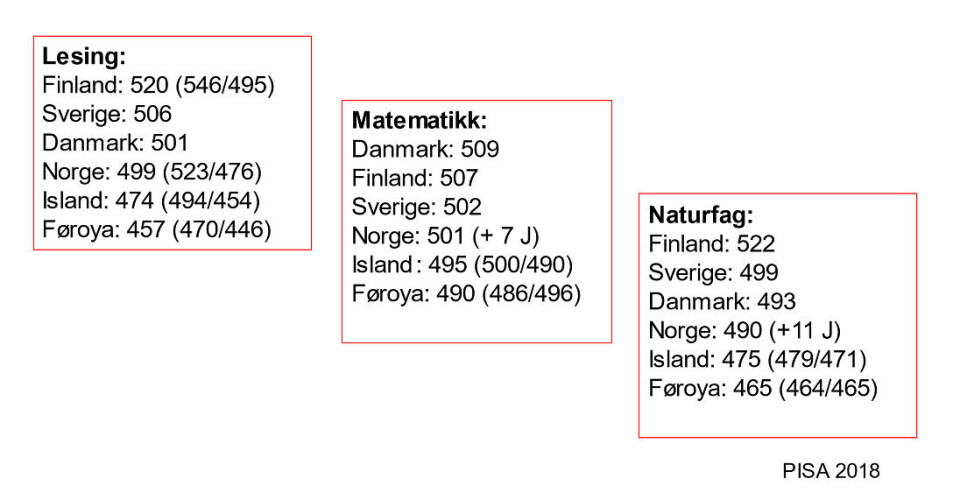

“Finland scores best in the Nordic countries on PISA tests in both reading and science, but is outscored by Denmark in mathematics. Norway is in fourth place in all categories, ahead of Iceland and the Faroe Islands,” Sigmundsson says.

Still plenty to work on in Iceland and Norway

So while the Icelanders can show excellent results for the youngest pupils, their progress doesn’t look as bright as time goes by.

Both Norway and Iceland clearly have something to learn from Finland if the goal is to do better on the PISA tests. Targeted practice and follow-up are key.

“Children in Iceland get off to a good start. But it looks as if this is not being followed up on well enough through reading books, writing, working to increase vocabulary, and so on,” Sigmundsson says. “It may be that we’re not developing language understanding well enough in Iceland, which it is key for reading skills.”

Reading skills require the ability to decode text, by learning the letters and sounds, but also language comprehension. This last component is probably what the Icelanders have not achieved quite yet.

The researchers have not yet measured the vocabulary of Icelandic children, but Finland and Norway may have a leg up on Iceland in this regard during the kindergarten years.

In order to improve the results, researchers will need to establish a baseline before children start school.

“We’re now developing a test to measure the vocabulary of 3-year-old children,” Sigmundsson says

Reference:

Thórsdóttir et al. Letter-sound knowledge in Icelandic children at the age 6 years-old, Acta Psychologica, vol. 237, 2023.

More content from NTNU:

-

Why is nothing being done about the destruction of nature?“We hand over the data, but then it stops there"

-

Researchers now know more about why quick clay is so unstable

-

Many mothers do not show up for postnatal check-ups

-

This woman's grave from the Viking Age excites archaeologists

-

The EU recommended a new method for making smoked salmon. But what did Norwegians think about this?

-

Ragnhild is the first to receive new cancer treatment: "I hope I can live a little longer"