THIS CONTENT IS BROUGHT TO YOU BY THE University of Agder - read more

Dangerous poisons: Most gardeners still chose to use them

Norwegian gardeners have used pesticides for decades. Research shows that many of them had mixed feelings about the poisons they used.

“Discussions today are often too simple. Many say that pesticides are bad and organic farming is good. But it was never that simple,” says Hilde Kristin Røsstad.

In her doctoral work, she looked at Norwegian horticulturists' experiences with chemical pesticides between 1945 and 2021.

Røsstad is the fourth generation in a family of horticulturists, but she is formally educated as a historian and teacher. This combination is what sparked her interest in the recent history of pesticides.

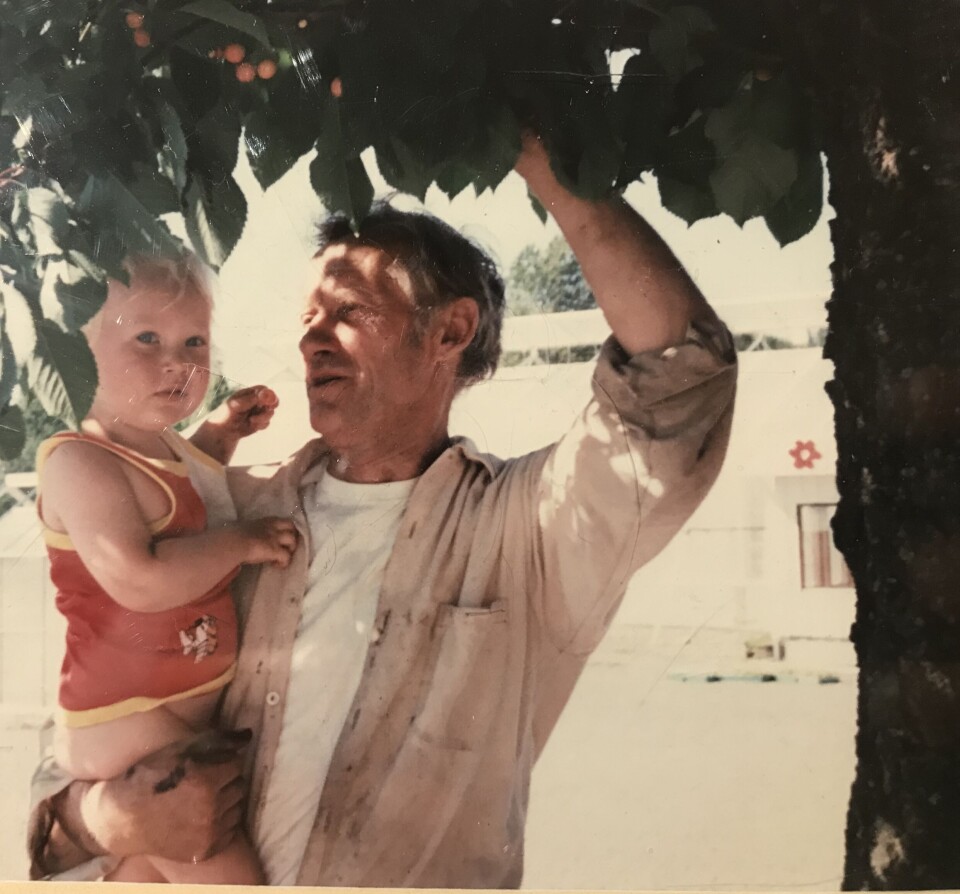

“After World War II, farming became more specialised. For example, orchards once had many different types of fruit trees – but by the 1950s, there was more or less only one type of apple left,” she says.

Part of this development was the increased use of artificial fertilisers and chemical pesticides.

“During this time, the use of such agents became systematic and almost a matter of course,” she says.

Spoke with 44 horticulturists

Røsstad interviewed 44 horticulturists aged between 25 and 95. She also studied diaries, trade journals, and archives.

The gardeners often had mixed feelings about pesticides. They knew the chemicals could be dangerous to themselves. Still, most chose to use them.

“These mixed feelings have always been there. They had to weigh the risk against being able to earn a living from growing plants and food,” says Røsstad.

She points out that gardening is very labour-intensive: Each plant must be carefully tended to be of high enough quality to sell.

“Horticulturists found that chemicals made their work more efficient. They could fight weeds, insects, and fungi that damaged crops,” she says.

DDT in bed

The oldest horticulturists she spoke to used highly toxic substances. Nicotine sulphate, Bladan, and Gramoxone were common. Such chemicals could also be deadly.

“One horticulturist told the story of a colleague who died after ingesting Gramoxone. He felt fine at first, but deteriorated after a few hours. By then it was too late,” Røsstad explains.

In the 1960s, attitudes towards chemical agents were different than today. A gardener recounted a story of a lady at the pharmacy who bought the insecticide DDT to powder her bedding.

“As she walked out the door, the pharmacist joked that it would have been better to wash the sheets. Nowadays it seems absurd. It shows how much perceptions of such toxic substances have changed,” says Røsstad.

Used their senses to detect danger

The study reveals how horticulturists used their senses to protect themselves. Smell was particularly important.

“A strong, foul smell was a sign of danger. If anyone noticed the smell of Bladan, said to resemble a mixture of garlic and rotten eggs, in the yard, they knew not to enter the greenhouse,” she says.

Many worked without protective gear. They relied on their senses, practised movements, and their own experience.

“You just had to make sure you didn't get too much on you or in you,” says a horticulturist Røsstad spoke to.

Several told of acute poisoning. The could become dizzy and nauseous from substances like nicotine and Bladan.

Pregnant women generally avoided handling pesticides. One story in the thesis describes three siblings arguing over whose turn it was to go out and spray.

One refused, while the others insisted it was her turn. Finally, she exclaimed: “But I'm pregnant!”

She was excused from spraying that day. Similarly, several horticulturists have become more aware of what they may have exposed themselves and their children to when using various chemicals.

Changing views over time

Røsstad found generational differences. Those who started as horticulturists in the 1970s and 80s were influenced by a growing awareness of the environment and safety.

Books like Silent Spring by American biologist Rachel Carson provided a different understanding of the impact chemical plant protection could have. These were insights the horticulturists gained through their work as well.

“The younger ones were more concerned about long-term effects and the environment. The older people thought mostly about the acute dangers that could be immediately felt,” she says.

It gradually became clear that it wasn't necessarily the size of the toxic dose that was decisive.

“Research showed that such substances can work over time. And for some chemical substances, small doses can have a greater effect than larger ones as they affect the hormone system,” says Røsstad.

Wants a better conversation

Røsstad believes her research can be important for today's debates about chemical pesticides.

Her work documents how complex this use has been and why gardeners have opted to use such toxic substances.

“These aren't just local anecdotes. They connect the local and the global and show how chemicals from labs in Germany or the US impact both human experiences and local ecosystems here in Norway,” she says.

Reference:

Røsstadm H.K. Handling Pesticides in Horticulture: Norwegian Horticulturists’ Perception of and Praxis with Chemical Plant Protection Products, 1945–2021, Doctoral dissertation at the University of Agder, 2025.

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

This content is paid for and presented by the University of Agder

This content is created by the University of Agder's communication staff, who use this platform to communicate science and share results from research with the public. The University of Agder is one of more than 80 owners of ScienceNorway.no. Read more here.

More content from the University of Agder:

-

Fear being rejected: Half pay for gender-affirming surgery themselves

-

Study: "Young people take Paracetamol and Ibuprofen for anxiety, depression, and physical pain"

-

Research paved the way for better maths courses for multicultural student teachers

-

The law protects the students. What about the teachers?

-

This researcher has helped more economics students pass their maths exams

-

There are many cases of fathers and sons both reaching elite level in football. Why is that?