THIS ARTICLE/PRESS RELEASE IS PAID FOR AND PRESENTED BY UNIS The University Centre in Svalbard - read more

When fieldwork doesn’t go as planned

Doing fieldwork on Svalbard is challenging. Here, students tell of some of their more memorable experiences.

Robynne Nowicki is a PhD candidate in Arctic Marine Biology. Her PhD is a part of the Nansen Legacy project, Norway’s largest marine research project. She’s spent several weeks on a research cruise in the Barents Sea, and here she tells of one of the mishaps.

“We were ready for our new venture – catching amphipods under the sea ice. Our task was simple: attach some amphipod traps to the ice edge, let them hang in the water, mark the spot with a flag and wait for them to fill up with the tiny crustaceans.”

What they didn’t consider was that the smell of the rotting fish bait inside the traps would not only attract the little amphipods, but a huge polar bear!

“Emerging from the endless plain of ice, this bear makes a bee line for our traps, rips one out of the water and gives it a munch. Luckily for us though, it was much more intrigued by a GPS logger a few meters away, so proceeded to go give that a munch instead!”

They left the traps for the night with the plan to collect them the next morning, only to find out the sea ice had moved during the night, trapping the traps under the ice forever. The only trap that survived was the one pulled out by the polar bear, containing a grand total of zero amphipods…

Annoying bears

Curious polar bears also put an end to Victor Gonzalez Triginer’s fieldwork in Billefjorden this summer as he was using an Unmanned Surface Vehicle (USV) to study macroalgae and fish.

“While we were driving the USV in Petuniabukta, we saw three polar bears, a mother and two cubs far away on the shore. As they were far, we continued with the work while keeping an eye on them,” he explains.

At some point however, the polar bears went in the water and started swimming directly towards the scientists.

“We decided to pack up and go to the other side of the bay in order to not disturb the bears and avoid them getting too curious of our USV. Shortly afterwards we saw they had returned to the shore. ”

He adds that there was no danger at all, as the bears were far away. The scientists were quick to leave the area, nevertheless, mildly annoying for the progress of their fieldwork.

Look up, look up

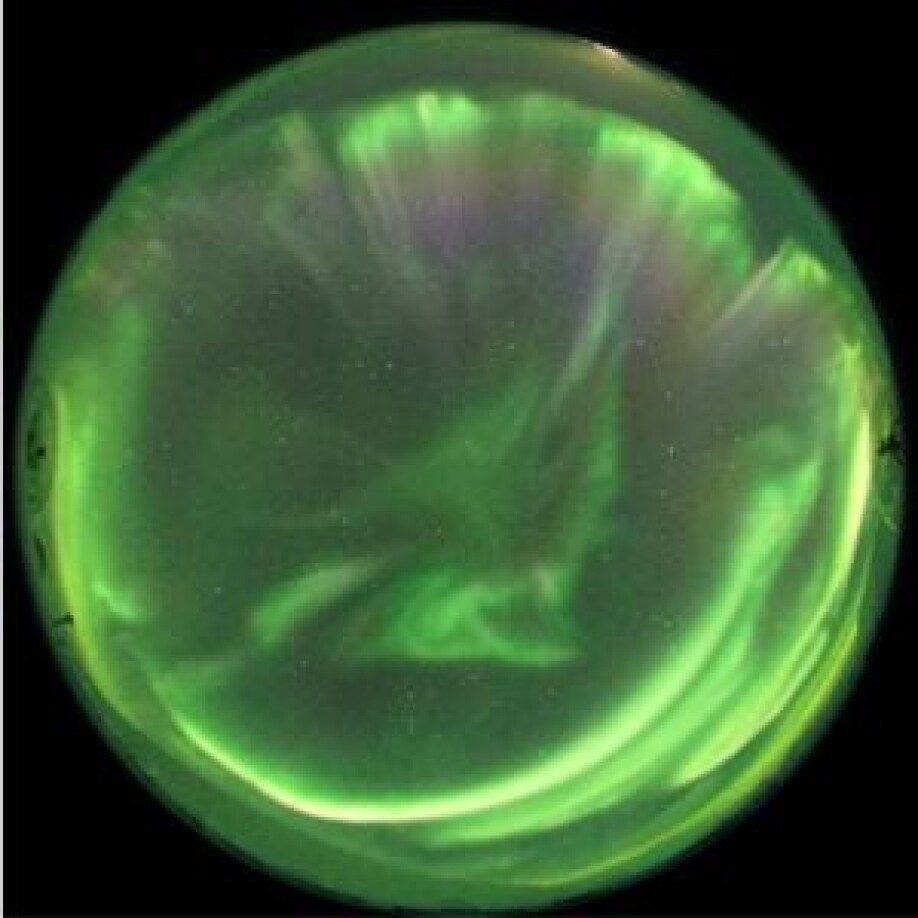

Jonathan Ackroyd, a Geophysics master student remembers a week in March when he was doing fieldwork at the Kjell Henriksen Observatory.

“It was cloudy all week, and we saw nothing. Then we had another week up there with people using the Eiscat sensors to study aurora. Again, there was nothing to see for the first day, but then we had the best night of aurora of the year. It was a fantastic solar storm!”

Sounds good, right? Wish we’d been there. Nevertheless, things didn’t go as planned.

“For some unknown reason something on the radar broke, and we couldn’t get any data. We got some great pictures though!”

Lost and found

Andreas Alexander is a glaciologist who’ve spent the better part of the summer doing field work at Kongsvegen glacier. It has been hard work, with 340 kilometres of hiking up and down the glacier with heavy backpacks and more than 1500 kilometres in a boat with tricky swell and ice in the water.

The aim of the fieldwork was to do a glacier lake outburst flood study. The researchers’ goal was to measure a glacier lake formation and monitor it until its sudden drainage into the fjord. They expected a drainage of millions of cubic metres within 1-2 days.

The problem was that the glacier lake would not drain.

“Frustration continues. The lake level is still going up, even though the speed seems to have slowed down somewhat. The glacier next to the lake starts to make weird sounds. Continuous cracking, buzzing and plumbing sounds. Something is going on. It’s just not draining yet,” Alexander wrote in an update.

They also sent more drifters into the glaciers, however the antennas at the glacier front never picked up any signals. In the end, Alexander had to call for help.

“The drifters might still be stuck inside the glacier; the antennas might have been too far away to pick up a signal or the sediment in the water might have interfered with the radio signal. We’ll probably never find out. Arctic field work never goes according to schedule. Would be boring otherwise.”

Editors’ note: the lake drained three days after the researchers had left the scene…