THIS ARTICLE/PRESS RELEASE IS PAID FOR AND PRESENTED BY UNIS The University Centre in Svalbard - read more

Data is our key to understanding the world in the future

The future is a world full of standardised data that is easily accessible and understandable to all.

Anyone will be able to retrieve and display global maps of different parameters with a few clicks of their mouse – or maybe by asking their voice-controlled smart assistant. This will revolutionise how scientists work and how easy it is for members of the public to access, understand and engage in science. But the first step is for scientists to publish their data in a standardised way.

The Nansen Legacy project is now turning from heavy field activity, deployment and pick up of instruments and satellite monitoring over to results. The project has collected millions of samples and data from expeditions since 2018 and has gained even more knowledge about the Arctic and Barents Seas' seasonality.

We have asked data manager Luke Marsden (UNIS), who oversees our data legacy in the project about his important work. He is already known for his role in bringing scientists together to share and use data in the best possible way.

A lot of old knowledge and data had to be updated, and consisting of 10 different institutions with different disciplines, The Nansen Legacy project needed someone to advise on how to manage the collected data following the best practices available.

The oh-so-important data

The definition of the word ‘data’ is incredibly broad. The word derives from the plural of the latin word “datum” which means ‘a thing given’.

"But what is data?"

“I think this has evolved to something like ‘information about a thing’. When most people think of data they think of numbers, but data can be descriptive, facts, or even things like images. For me, data is what drives knowledge, so really any information about any object can be considered data if it is the subject of some research – and research in the broadest sense too,” Marsden says.

Better for the future scientist if we publish our data now?

Scientists in the Nansen Legacy project have collected data all the way from outer space to under the bottom of the ocean.

We wonder if this is a lot to handle for one person, and Marsden nods.

“I agree, it would be. But my job is to help people manage their data themselves, not to do it for them. There is far too much data for me to manage alone. Mostly my job is to teach people how to manage their data and develop tools or applications that make this easier for them. Researchers should publish their data, but historically, this has been a big problem in academia,” he says.

According to this Nature paper, only 20 per cent of research data is available 20 years after a scientific paper has been published. So, it is the job of a data manager to drive a culture change when it comes to publishing data as much as it is to teach people how to publish their data.

“Good communication skills are an important part of being a good data manager – something I didn’t realise when I took the job! I really enjoy this part of the job, whether it be writing e-mails, running workshops, giving presentations, or even creating YouTube videos - I try to spread any wisdom I have as broadly as possible,” he says.

From volcanoes to engaging data

Luke Marsden has a background in geophysics. He worked in seismic data processing in the oil and gas industry for three years before leaving to do a PhD in physical volcanology at the University of Leeds.

“I love volcanoes, but my family and I wanted to move to Norway since my wife is Norwegian, and since there aren’t many volcanoes or volcanologists here, I started to look for other jobs. I wanted to do something that moves us as a global community towards a better and more sustainable world – I felt like I was doing the opposite of this in the oil and gas industry!” he says.

For Marsden, data management ticked all the boxes. It is very inefficient for everyone to collect their own data in terms of time, money, and emissions.

“The more data we publish, the more data we can use and reuse, and the faster science progresses. After all, we are likely to need research that uses big, multidisciplinary datasets if we are to tackle many of the big environmental, societal and economic issues we are facing,” he says.

Data is important – for everyone

Marsden has already done an excellent job for the project, not just building the framework for the data, but also building capacity within the project membership to do data handling properly.

As the project is striving to build a complete picture of the Barents Sea, these data are very important building blocks to achieve that goal. One of the challenges is to keep people interested in sharing their findings.

“What makes this particularly tricky in Nansen Legacy is that we work with data from many different disciplines. But the biologists need to know what the geophysicists are up to, and the meteorologists need to know what the oceanographers are up to. So we need a way to both keep track and present of all the data that we are collecting. We host a catalogue of metadata online – this doesn’t include the data itself, but instead includes who has been doing what, where and how,” he says.

If you are interested in learning more, you can watch this video on YouTube: Keeping track of data during Arctic expeditions here.

How to find knowledge

So now we have two ways to find the data; via paper, or by searching through the data stored by the data centre. But there are hundreds of data centres, so how do we find the data we are looking for?

“Some data centres are the default for a certain type of data. We have the Global Biodiversity Information Facility, for example, where most people publish their biodiversity data. This includes over 2 billion observations of different organisms worldwide. Some institutions have data centres connected to them. For example, scientists at the Norwegian Polar Institute should publish most of their data with the Norwegian Polar Data Centre,” Marsden says.

And then we also have data access portals. They don’t store any data, but instead provide access to data published with a variety of different data centres.

“For example, Svalbard Integrated Arctic Earth Observing System (SIOS) hosts a data access portal that aims to provide access to all data published in and around Svalbard. This should be the starting point for anyone looking for data from the region. All Nansen Legacy data is tagged so it is easy to get an overview of all the data we have published. The number of datasets included is growing all the time!” he says.

Finding and accessing data is one thing, understanding and being able to use them is another thing.

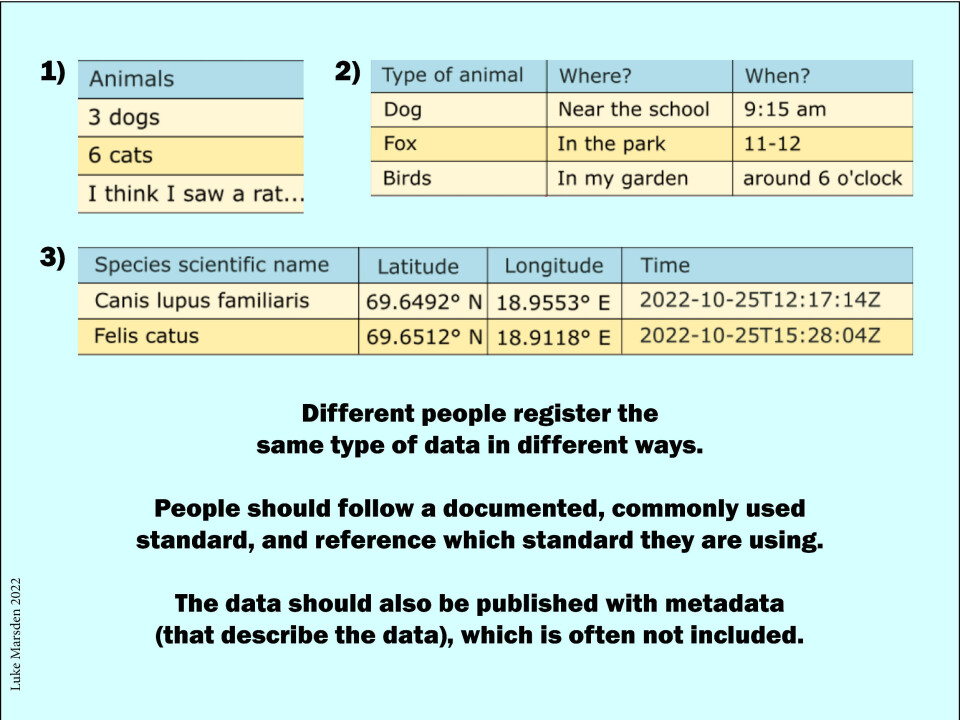

“Imagine you made an Excel sheet to log all the different animals you saw throughout the day. Imagine your friend did the same. Would your Excel sheets look the same? Would you have used the same column headers? Would you have structured the files in the same way? Would you be able to understand everything that your friend did without asking them? Probably not. Now let’s scale this up and imagine there are 1,000 people with 1,000 files. Would someone be able to write a single program to read and understand the data from all the files in the same way? Almost certainly not,” he says.

The importance of encouraging people

Through the Nansen Legacy project, Luke Marsden encourages people to publish their data in a standardised way.

“People should use file formats like NetCDF-CF or Darwin Core Archives where possible, which have a self-describing file structure, which means that the file includes information that tells a person or computer where everything is in the file. These files are self-containing, meaning that they contain a lot of metadata within the file that describes the data,” he says.

Further, he says that people should use terms that are commonly used, which are defined in so-called ‘controlled vocabularies’. These are glossaries of terms and descriptions that someone can find online.

The person creating the data can select an appropriate term and reference it. The person using the data can navigate to the same term. The data creator and user should then have the same understanding of what that term means, and a computer can understand the term too.

“If computers can understand our data, they can more easily present many similar datasets together in the same way, which makes it easier for people to view, access or understand the data,” he says.

Marsden has made a good habit amongst the early- and mid-career scientists and given them tools they will carry with them into the rest of their careers. Maybe this is the legacy of the project?

“Absolutely. We have a data policy which researchers have to abide by. But I hope they do so because it is the right thing to do, not just because they have to! And I hope they carry these good habits with them into future projects. A data revolution is coming, and one’s track record of publishing data is starting to be considered in deciding who gets funding or who gets hired for a job. Data is finally becoming more valued, and those publishing their data should be credited and rewarded,” he says.

User-friendly data for everyone?

As the project received funding for giving a good knowledge base of the Barents Sea, we now see that we can already update weather models or forecast the edge of the sea ice with the use of this new data. The data is now ready for future use.

“The data we collect will be used in research for decades to come, maybe centuries in some cases. We are building a multidisciplinary picture of the Northern Barents Sea, one of the fastest warming places on the planet. If we want to understand the changes taking place here, we first must document the data. By publishing our data, we are making it easier for more people to research what we are observing. We can contribute to big datasets, far too large for any one person or project to collect alone,” Marsden says.

He claims that the quicker we do this, the quicker we collectively understand what is happening in the Northern Barents Sea and why, which will likely have global implications. It all starts with the data.

“Perhaps even more importantly, we are setting a precedent for how data should be handled and published for the rest of Norway and the Arctic. Good data management is in its infancy in the Arctic but is much more mature in other fields. Take the World Meteorological Organization for example. We would not have such high-quality weather data or climate models without international exchange of standardised data. Who knows what will be possible with similar exchange of data becomes common practice in other disciplines?” he asks.