This article is produced and financed by University of Oslo - read more

US oil money kick-started The Norwegian Institute of Public Health

The Norwegian welfare institution is not as Norwegian as many people think.

March 12th 2020: Norway shuts down to halt the spread of Covid-19. The decision is made in close consultation with the country's foremost health authorities: The Norwegian Directorate of Health (Helsedirektoratet) and the Norwegian Institute of Public Health, NIPH (Folkehelseinstituttet).

The fact that the health of the population is the responsibility of the government is taken for granted in the Norwegian welfare state. But it hasn't always been that way.

“Before building up the welfare state in Norway, we received financial support from the United States for public health work. So what is often assumed to be a Nordic phenomenon – governmental responsibility for public health – is actually partly American”, Sunniva Engh says.

Engh is an associate professor of history who has recently investigated the link between an institution which is a cornerstone of Norwegian welfare: the Norwegian Institute of Public Health, and an American oil magnate.

Without US assistance, Norwegian public health work would have looked different today, she thinks.

The need to improve public health

At the turn of the 20th century, syphilis, smallpox and tuberculosis were ravaging diseases. Welfare schemes and health care were sorely lacking.

“Many different actors contributed in the field of health: The Norwegian Women's Public Health Association (Norske Kvinners Sanitetsforening) and the Red Cross trained nurses, and the hospitals were sometimes privately operated”, Engh says.

“There was a consensus in the Norwegian medical and health policy communities that the government's ability to develop vaccines for the population was insufficient”, she says.

Laboratories had been established at the National hospital, Rikshospitalet, but much more was needed.

Both medical and political professionals wanted an institute of public health with a larger capacity to produce vaccines and make them available, as well as to analyse food and drinking water and to train medical personnel. The area Geitmyrsveien, which at the time was in the rural periphery of Oslo, was designated as a suitable site for the institute.

“When the Norwegian parliament and the Ministry of Social Affairs gave the green light, the plot in Geitmyrsveien was purchased in 1920", says Engh.

Additional grants were also made, but suddenly, in 1921, there was a complete reversal and the allocated money could not be spent after all.

Harder economic times in Norway had resulted in cuts in health and social work and quashed the plans for a Norwegian institute of public health.

Oil magnate with an idealistic wish to boost international health

At the same time, Norwegian physicians have come into contact with international medical communities, and with the help of generous scholarships, they have travelled abroad to learn about the latest developments in the field. The funds are from one man in particular: John D. Rockefeller and his philanthropic institution, the Rockefeller Foundation.

“Rockefeller had amassed a lot of money from oil extraction and oil trading. He was the richest man in the world at the time, and a philanthropist - a parallel to Bill and Melinda Gates today”, Engh says.

He was deeply religious and wanted to give something back to society.

“In 1913, he established a charitable foundation and began medical work in the United States. They focused in particular on fighting diseases and problems in the southern states in the US, and as the foundation became successful, they realised that this was something they could do internationally”.

The foundation created its own international health division and collaborated extensively with the League of Nations, the forerunner of the UN. Soon the foundation became central in international health work.

“The League of Nations was a new entity and did not have much funding. Rockefeller did, however. At one point, their funding amounted to as much as 40 per cent of the League of Nations' budget for medical work”, Engh says.

The historian points out that a number of authors believe that the Rockefeller Foundation was not only a participant, but a game changer in international health.

“They set the agenda, which they were able to do by virtue of a large network and great financial impact”.

Through the funding of the League of Nations' work, arrangements were initiated for training and exchange, permitting medical personnel to meet across borders.

Rockefeller was eager to professionalise and standardise medical expertise.

“They commissioned large studies that had a great impact. When the national experts met to exchange views, the Rockefeller Foundation had already done much of the thinking for them”, says Engh.

Norwegian-American contact

Over the years, the Rockefeller Foundation has collaborated with 90 countries. One of these is Norway.

“Norwegian medical personnel who travelled to New York brought their knowledge back home and implemented it”, says Engh.

But knowledge was not all they gained. Rockefeller was now looking to Scandinavia; he wanted to do something for public health work here.

“So whereas the Norwegian medical community lacked money and the Parliament could no longer help, Rockefeller wanted to get actively involved in the Scandinavian countries”, Engh says.

Two communities find each other: one wants to expand; the other needs the funds to put their plans into action.

The plans were unmistakably similar, and Engh has no doubt that the Norwegian medical profession was influenced by ideas from the USA.

“It was Rockefeller's reports that Norwegian medical professionals learned from on their trips to the United States. Rockefeller wanted to establish public health institutes that would take on a role of leadership in public health work. Thus, it is not surprising that the money and mindset Rockefeller stood for in medicine fit hand in glove with the need that was present in Norway”.

Christmas gift from America

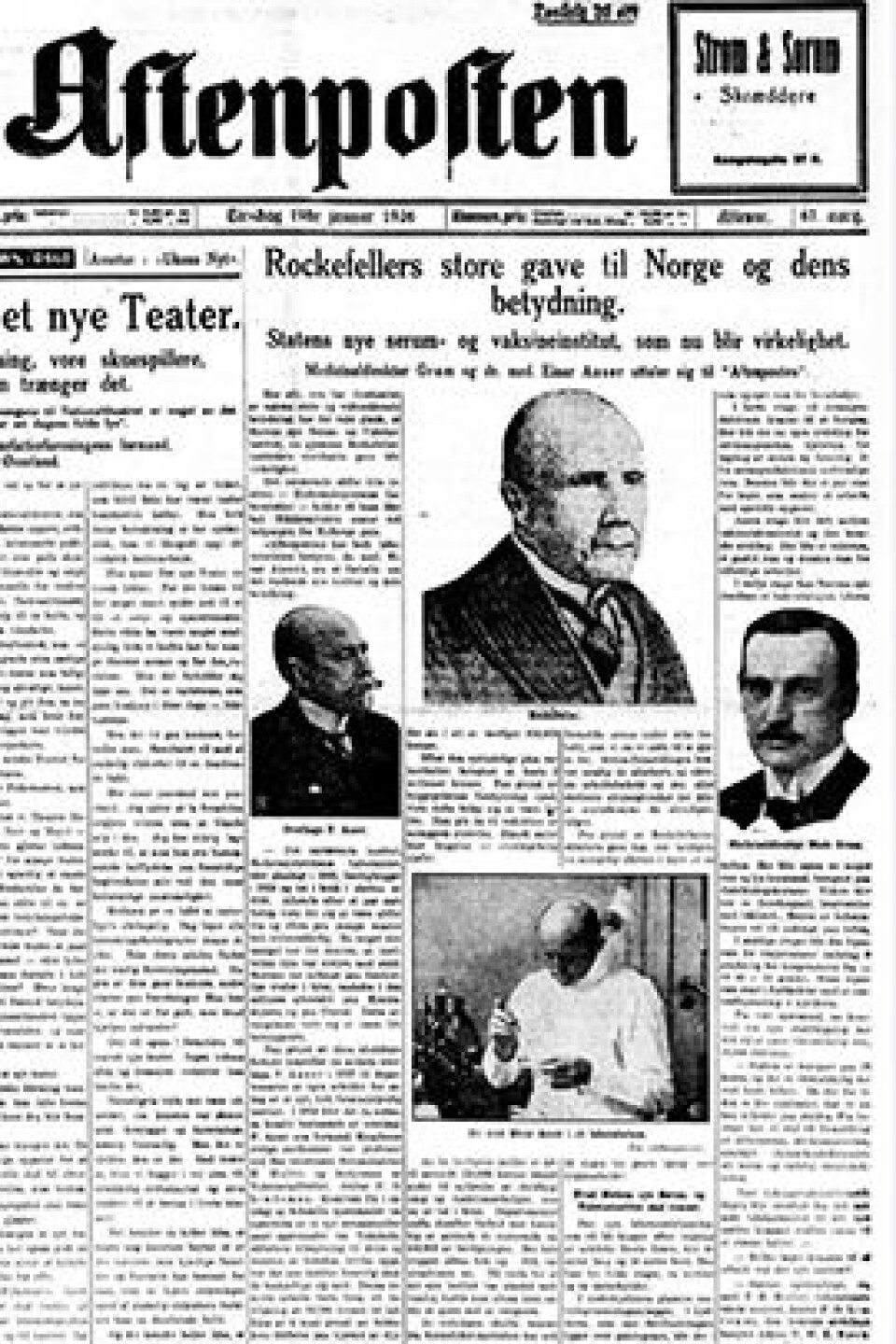

On 19 January 1926, readers of the Aftenposten newspaper learned about ‘Rockefeller's grand gift to Norway’. A total of NOK 1,085,000 was allocated for the construction of what was called the national government's new serum and vaccine institute. The news was enormously exciting, and it was given much coverage in the press. Finally, plans could be put into action.

“The grant in 1926 went to construction, followed by annual sums of money for equipment, recruitment of personnel and so on”. The institute was established in 1929 and was officially opened in 1930.

There was little scepticism towards the gift.

“Even the communist publications cheered the funding. I have browsed newspaper archives from the time when the public learned that the money had been granted for the establishment of the institute, and was unable to find a single critical voice. It was looked upon as a gift”.

It is true, nevertheless, that Norway had to commit to funding the Institute of Public Health in the longer term. The money that parliament had put on hold would eventually have to be put on the table.

“Norwegian health authorities had to fund their share of the institute, and they also had to guarantee continued operations after the funding from the Rockefeller Foundation expired”.

Public health is a government responsibility

One central notion of the Rockefeller Foundation was that public health was the responsibility of the government.

“The idea was that the way to improve the health of the entire population was to get medical personnel to address individual citizens. There was a great belief in public education, and that thereby, individuals would take responsibility for their own health. But they thought that this public education effort should be run by the government”, Engh says.

Similar lines of thought can be found today in Norway's foreign aid work.

“This is precisely the kind of help the Norwegian Institute of Public Health, in cooperation with Norad (The Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation), is trying to provide other countries today. They have helped establish public health institutes in other countries, and they believe that these are essential as an opportunity to respond to crises, such as the pandemic we are experiencing now”.

Sunniva Engh’s findings, in her opinion, are important for adjusting the image of the welfare state model as a special trait of Norway and the Nordic countries.

“It's easy to look back and think that the cross-political consensus we had in the post-war period concerning the welfare state has always been present. But it did not exist when the Norwegian Institute of Public Health was established; it came afterwards. Both the idea that the government should be responsible for citizens' health and the funding to establish what have become key institutions in the welfare state should therefore not be automatically perceived as something typically Norwegian or Nordic, but instead as something that also came from the USA”, she says.