This article is produced and financed by University of Oslo - read more

Norway multilingual since the middle ages - mixed runes and letters, Old Norse and Latin

When Latin arrived in Norway, Old Norse written culture also flourished. New research shows that runes and letters were used in alternation.

The fact that Norwegians wrote with runes in the Viking Age and Middle Ages is well known. But what happened when alphabetic writing arrived and we switched from runes to the letters we know today? New research on inscriptions with letters shows that the transition was far slower than many believe.

“We find inscriptions with letters and runes from the same time, on the same kinds of artefacts,” says Elise Kleivane.

“Here, the writing is in both Old Norse and Latin, and we see that runes and letters could be used for the same thing. What is interesting to see is what people chose to write in what language, and with what kind of alphabet,” she says.

Kleivane is an Old Norse philologist and associate professor at the Department of Linguistics and Scandinavian Studies (ILN) at the University of Oslo. Together with doctoral fellow Johan Bollaert, she has done research on precisely these inscriptions.

The written culture flourishes

The first written language culture in Norway begins with the runes in the 100s AD. Researchers assume that an oral culture mainly prevailed at this time, but inscriptions have been found on stone, metal and wooden sticks.

“Based on what has been preserved, it looks as though there has been limited use of runic writing. Memorial stones have been found along with jewellery and precious artefacts, usually with names or other relatively short inscriptions. They probably wrote on more things than we have found – on birch bark, in the sand or on wood,” says Kleivane.

In the early written sources of writing from the Viking Age, the texts are often short and there are not many of them – preserved at least. A common example is gravestones, with standard formulations about the person buried underneath. When the Latin language and writing system came to Norway with Christianity around the year 1000 AD, this changed.

“People began to write more – also with runes,” says Kleivane.

There was a lot of international contact during the Viking Age, and Scandinavians embarked on journeys to countries with a stronger written and Christian culture. Here they saw that society was organised in other ways. When the Christian culture and letters arrived in Norway, reading and writing skills changed, but also the scope and meaning of writing.

”People saw what they could write, and what you could do when you write. It appeared to give writing, including runic writing, a real boost.”

Latin used in Church

As we move from the Viking Age to the Middle Ages, the Church is established and royal power is centralised. One could imagine that the runes would disappear, because now we have letters. But this is not the case.

“In the Middle Ages – and especially in the High Middle Ages, runes abound. Everyday messages on wooden sticks were common then, but also writing on things that supposedly embodied magical or medicinal powers. Prayers and incantations are found. These were written in runes or with letters, and in both Old Norse and Latin.”

There is a clear overlap, both with the writing system and with the language. They can be used for the same thing, but tendencies are seen in different areas of use.

“Old Norse was the mother tongue, Latin had to be learned. In certain functions of society, it was more appropriate to use Latin.”

Latin was used by the Church and it was often those educated as priests or high officials who knew the Latin language. But looking at the entire Middle Ages, this division appears to be too simple, according to Kleivane.

“There has been a tendency in research and in the Norwegian consciousness to think that Latin was oppressive. But that’s not the picture that emerges when you look at how it was used,” she says.

It was common for everyone to learn the Apostles’ Creed, the Lord’s Prayer and Hail Mary. All of these prayers are found written down in Old Norse, which suggests that it was not impossible or unlawful to translate them into the vernacular language. But Kleivane thinks many still wanted to pray in Latin.

“They probably experienced that it should be like this, maybe it seemed more correct, more powerful, in Latin,” she says.

Wild mix of runes and letters

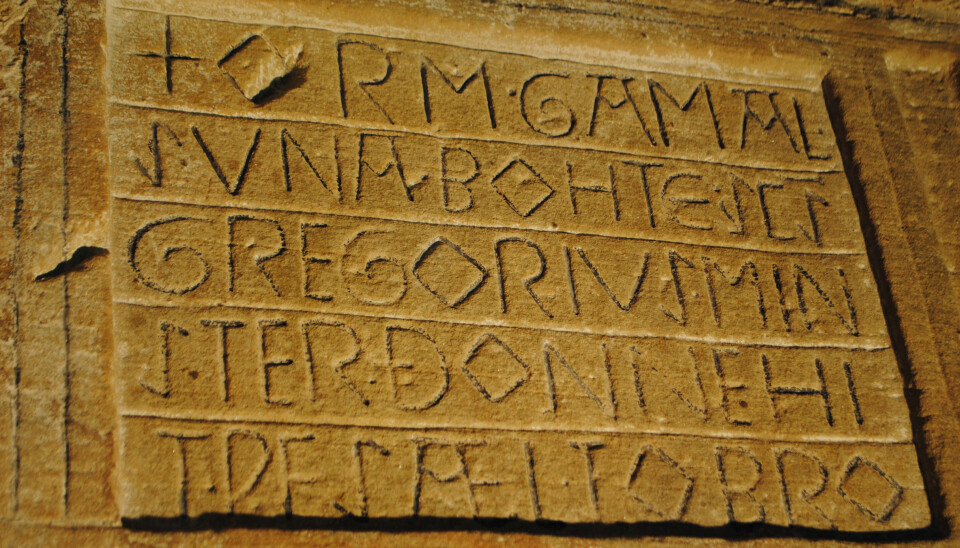

Kleivane believes it is clear that people chose runes or letters according to what function the writing was to have. But in several cases they find a curious mixture: Runes and letters alternating with each other. An example of this is a tombstone from Trøndelag county.

“Here, the inscription on the grave starts with letters, in Old Norse. But then, in the middle of the word ‘faþer’ ('father'), when you get to the þ ('thorn') – that is, the letter that was not found in the Latin alphabet, it switches to runes. And then the rest of the inscription is in runes.”

She believes that which alphabet was used says something about who it was written for, and who wrote it. But she doesn’t have an explanation for such sudden shifts.

“You can’t chisel letters into a stone without having thought in advance about how it will end!”

Awareness of the function of writing

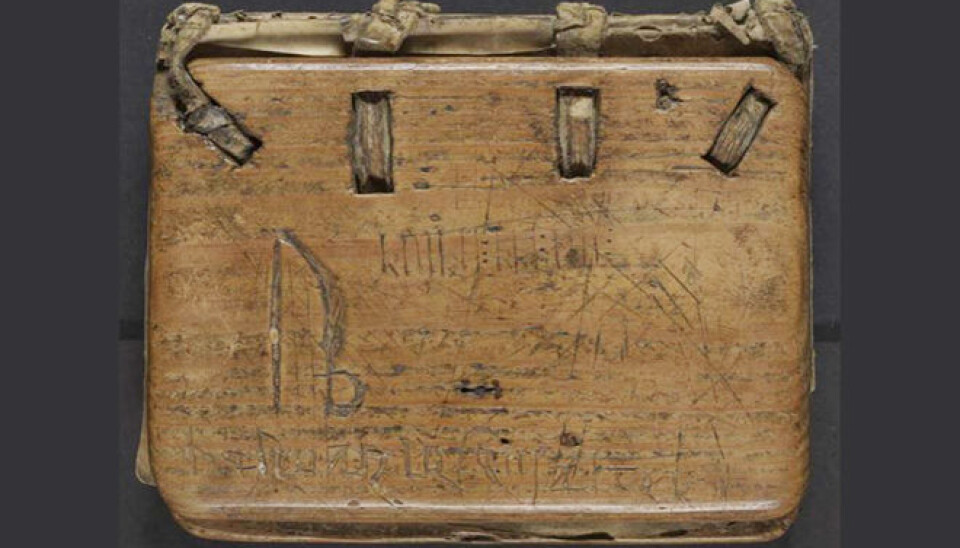

Another artefact that has become an important source for the researcher is a so-called psalter – i.e. the Book of Psalms from the Bible – from Kvikne village in Tynset Municipality.

“In an inscription on the cover, runes and letters are mixed: all of the k-s except for one are letters, the rest are runes. The text in the psalter itself is in Latin with letters, and on the cover there is another inscription in Old Norse that is only in letters.”

The psalter is typical of much of what Kleivane found: Artefacts have been archived and it is noted if there are runic inscriptions on them. But few have cared about the letters.

“The artefact itself is interesting because it mixes so many aspects of writing and uses of writing. It is a starting point for telling us a lot about the history of language,” says Kleivane.

The inscriptions with letters and runes may indicate that people had a developed awareness of what they wanted to achieve with the texts they wrote. Runes were often used for short and spontaneous messages, letters more for longer texts that were to be in force for a long time. But there are always exceptions.

Do not underestimate people in the old days

We find texts in both Latin and Old Norse in both letter inscriptions and runic inscriptions, bearing witness of a bilingual culture. Elise Kleivane believes it cannot have been all that unusual to have some knowledge of Latin.

“Learning Latin is not black magic. It’s possible to learn a fair amount of Latin during a lifetime. And many knew a little.”

Perhaps we underestimate people from the old days?

“Yes!", exclaims the researcher.

"And the same goes for reading. Imagine an altarpiece in the church inscribed with Hail Mary. You don’t have to hear it very often before you recognise the writing. That’s how children learn what writing does, after all.”

Latin never gained precedence in Norway, which fits well with the national self-understanding, according to Kleivane.

“It might have happened, but Norwegian, or Nordic, and Latin were such structurally different languages, so it is difficult to imagine that they could have merged into a new language. Moreover, when Latin arrived here, it was no longer the mother tongue of anyone. Other European languages, such as French, Spanish and Italian, are a development of Latin. Those who were 'Latinised' in Roman times had a completely different language history.”

Letters are important in Norwegian language history

The runes disappeared towards the end of the Middle Ages, although signs have been found that they were used as late as the end of the 15th century. In a Nordic context, it is the runes that have attracted the attention of philologists. The artefacts Kleivane has studied have often been known and previously studied. But the lettering on them is not mentioned – at least not as sources of written history.

“Letters and Latin exist throughout Europe, so the thinking has been that it does not tell much about us. But it does! When you start viewing it as a source of language history, we see that they say a lot about the development of the writing culture we have today,” she says.

———