THIS ARTICLE/PRESS RELEASE IS PAID FOR AND PRESENTED BY the Institute of Marine Research - read more

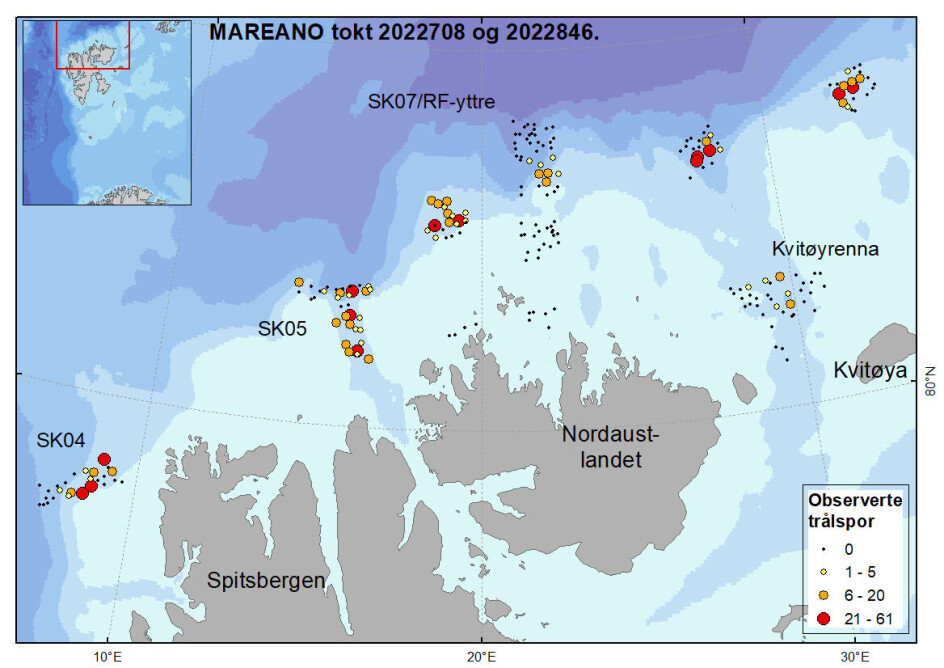

High concentration of trawl marks north of Svalbard

Before surveying the area, scientists expected to find large areas of untouched seabed – and the odd trawl mark left by fishing boats.

“At the most popular fishing depths, we observed trawl marks at as many as 52 per cent of the locations surveyed. In total, we studied 233 locations at varying depths, and overall there were trawl marks at 35 per cent of them,” marine scientist Pål Buhl-Mortensen says.

He was the expedition leader on two mapping surveys carried out as part of the Mareano programme this summer. The surveys covered selected areas north of Svalbard, with participants from the Geological Survey of Norway and the Institute of Marine Research (IMR).

Highest concentration of trawl marks at 200-400 metres

Bottomtrawls have been used to catch shrimps north of Svalbard since the 1970s, but the number of trawl marks on the seabed was previously unknown.

“We thought that fishing in these northern waters was something which had increased in recent years, but our observations clearly show that there has been a lot of trawling here for many years," Buhl-Mortensen says.

Trawl marks were observed at depths of 160 to 900 metres, and particularly between 200 and 400 metres:

“In this depth range, over half of the locations had been trawled by fishing vessels,” he says.

At each location, the scientists studied the sea floor with underwater video cameras along a 200-metre sector.

“We counted up to 62 trawl marks at the locations we studied. So there was only three metres between marks in the places with the highest incidence," he says.

Very conservative estimates

The figures are based on what the scientists call definite trawl marks; they don’t include 'possible trawl marks', as they are uncertain.

“If we had included possible trawl marks, the number of observations would have been even higher, but then it would also add uncertainty about the extent to which we had included marks caused by natural processes such as landslides and strong currents,” Buhl-Mortensen says.

Trawl marks are clear to see

For this survey, the scientists used a remotely operated mini-submarine – a so-called ROV – to examine the seabed.

“It was equipped with a kind of radar or sonar with a 50-metre range. It allows us to see the trawl marks very clearly,” Buhl-Mortensen says.

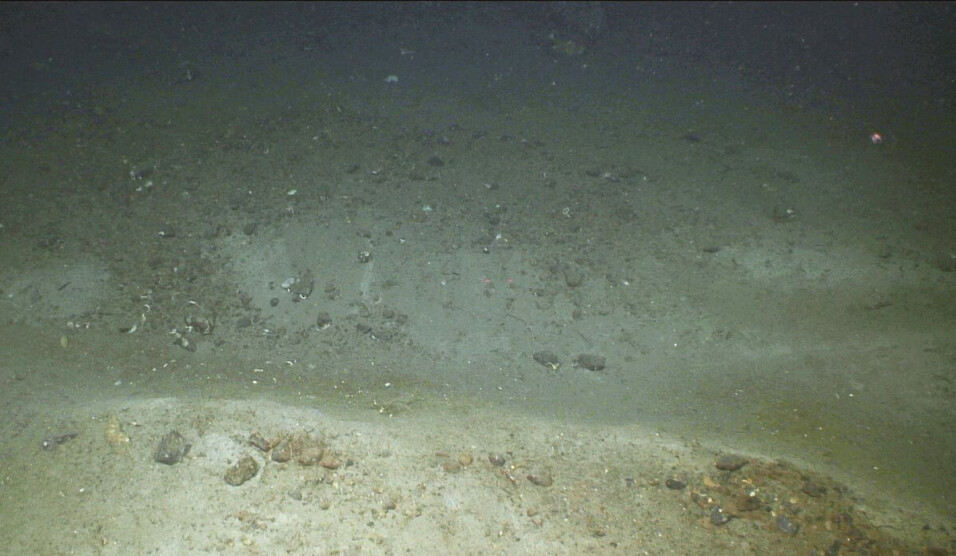

Trawl marks are made by the fishing gear used by trawlers when catching fish. This gear is dragged along the sea bottom.

“The appearance of trawl marks can vary greatly, from superficial dragging marks to deep furrows," he says.

Trawl marks often appear as parallel furrows in the seabed, caused by the two doors that serve to spread the trawl net.

“In some places you can see in the sonar pictures how the trawl doors occasionally jump along the bottom. They dig themselves deep into the sea floor, and then they are lifted up to the seabed surface, before digging down again,” he says.

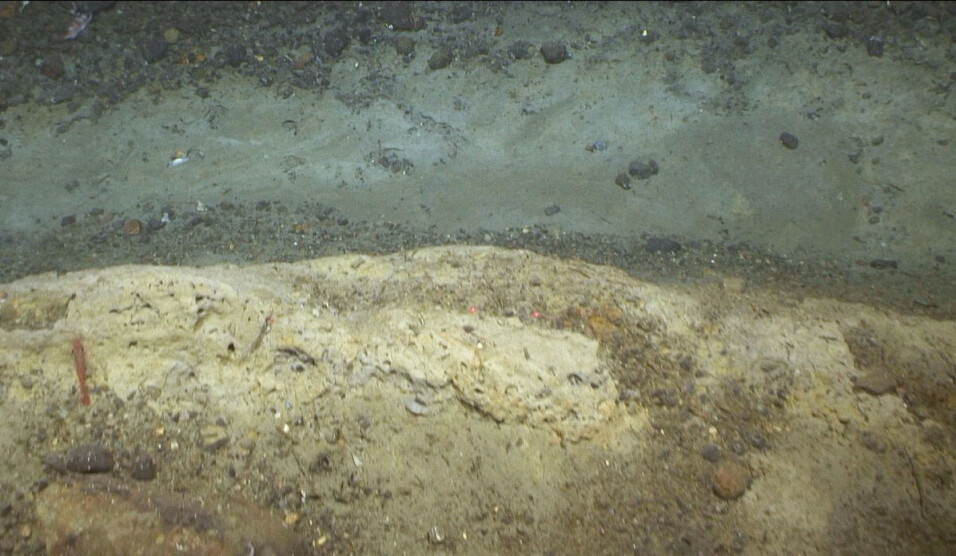

Seabed is disturbed and vulnerable species are destroyed

There are many vulnerable species on the seabed, many of which cope badly with trawling.

“For instance, this area has quite a lot of Umbellula sea pens, pigtail corals and bamboo corals. These species are considered vulnerable internationally. They are very vulnerable to external impacts and cannot cope with being trawled over,” Buhl-Mortensen says.

Unique discovery of bamboo coral

He particularly highlights the presence of the bamboo coral Isidella as unique. This species had previously been observed in Norwegian fjords and territorial waters south of Troms, at depths of 200 to 700 metres.

“North of Svalbard the bamboo coral is found at depths of 700 to 800 metres. The temperature there is around 0.5 degrees, which is at the bottom of the tolerance range for the species,” Buhl-Mortensen says.

At greater depths, down towards 1,100 metres, the scientists found areas with many bamboo coral skeletons.

“We observed bamboo coral skeletons at four locations, and at two of them there were also living colonies. At one location (770 metres below sea level), there were clear signs of bottom trawling. There we only found dead skeletons," Buhl-Mortensen says.

Bamboo coral forms a particular biotope, which is not considered to be under threat in most places where it has been found, but in the Norwegian Trench off Egersund it is red-listed as “near threatened”. North of Svalbard, this biotope had not been previously documented, although there had been unconfirmed observations in trawl by-catches during the IMR’s ecosystem surveys.

“The areas with bamboo coral found during this survey will be endangered if the use of bottom trawls increases. What has killed the deeper bamboo coral populations north of Svalbard is a mystery for now, but it may be that this Arctic population is particularly vulnerable to temperature fluctuations," he says.

Fishing vessels from many countries

During the surveys, they also observed high levels of fishing activity in the area:

“At times we were surrounded by trawlers from various countries. We saw trawlers from many EU member states, as well as Russian and Norwegian ones," Buhl-Mortensen says.

This article/press release is paid for and presented by the Institute of Marine Research

This content is created by the Institute of Marine Research's communication staff, who use this platform to communicate science and share results from research with the public. The Institute of Marine Research is one of more than 80 owners of ScienceNorway.no. Read more here.

See more content from the Institute of Marine Research:

-

Do whales compete with fishermen?

-

These whales have summer jobs as ocean fertilisers

-

Have researchers found the world’s first bamboo coral reef?

-

Herring suffered collective memory loss and forgot about their spawning ground

-

Researchers found 1,580 different bacteria in Bergen's sewage. They are all resistant to antibiotics

-

For the first time, marine researchers have remotely controlled an unmanned vessel from the control room in Bergen