THIS CONTENT IS BROUGHT TO YOU BY NIKU - Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research - read more

Archaeologists have uncovered a long-lost medieval market town at Hamar

Ground-penetrating radar surveys indicated that something lay hidden beneath the soil. Archaeologists have now uncovered actual building remains.

In the summer of 2023, the Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research (NIKU) pinpointed the location of the long-lost medieval market town of Hamar (Hamarkaupangen) using ground-penetrating radar (GPR).

During an ongoing excavation carried out by NIKU and Anno Museum, archaeologists have finally found physical remains of buildings, confirming the geophysical data.

Where is Hamarkaupangen?

According to the The Hamar Chronicle from the 16th century, an urban settlement once lay to the east of Hamar’s cathedral and bishop's residence.

The town was likely established around the mid-11th century, but it is unknown when it was abandoned. Of Norway’s eight known medieval towns, it is the only one located inland.

While artefacts have been found in the topsoil over the years, the physical evidence of this medieval town – its buildings, town plots, and streets – has remained elusive.

So, where exactly was this town located? Was there really a town at Domkirkeodden, or was it merely a seasonal trading site?

Over the past decade, NIKU has repeatedly used GPR to investigate the fields at Domkirkeodden. This time, the evidence they sought finally appeared.

Ground-penetrating radar was key

While this area has long been suspected as the site of the secular settlement, archaeological proof of an actual town has remained absent – until now.

A 16-channel motorised ground-penetrating radar system was used for the survey, the same equipment that identified the Viking ship at Gjellestad in 2018.

The geophysical survey was carried out by archaeologists Monica Kristiansen, Jani Causevic, and Ole Fredrik Unhammer.

The survey itself was carried out in one day. But interpreting the entire dataset took several weeks.

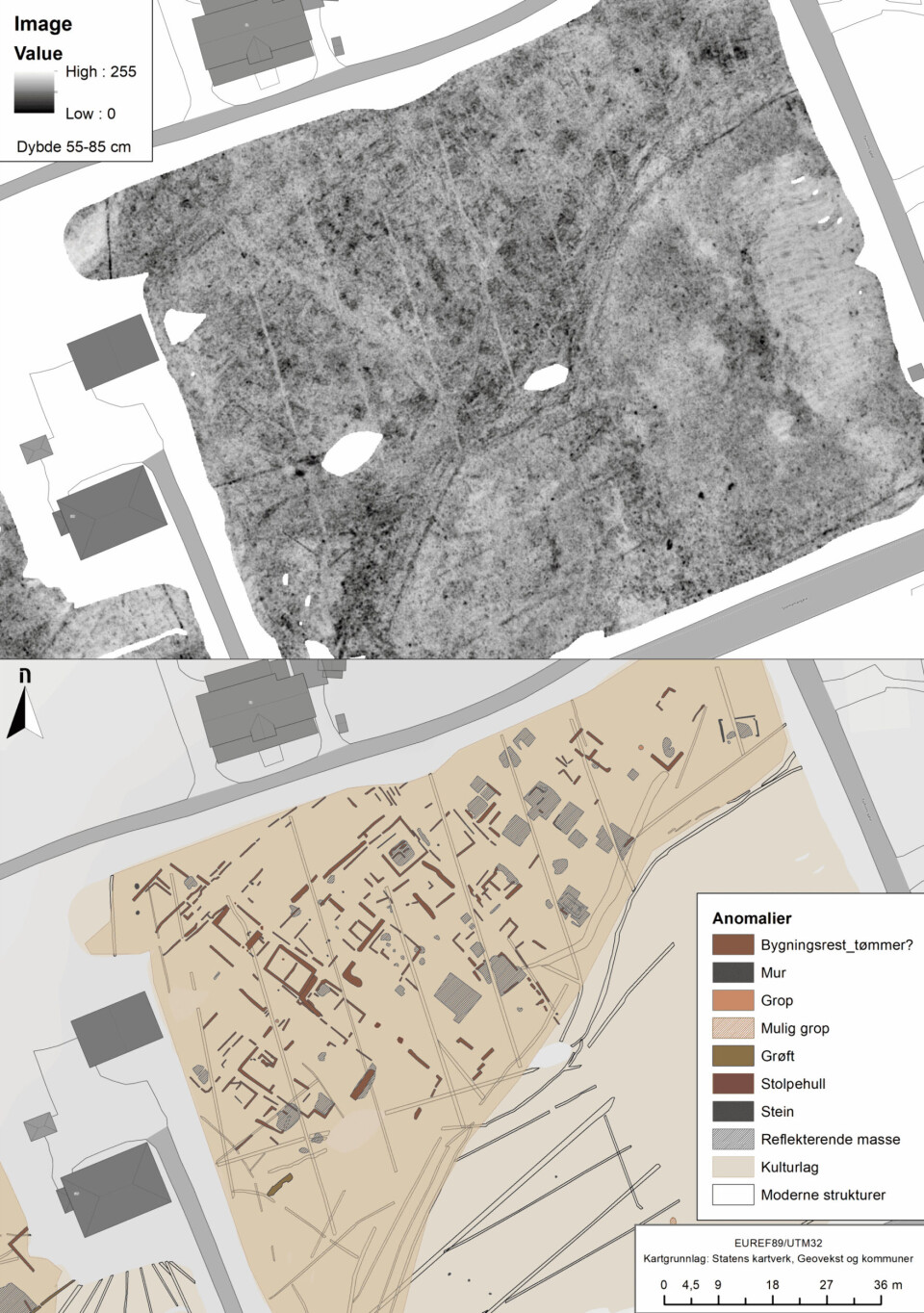

The radar data revealed features characteristic of urban structure, comparable to those in other known Norwegian medieval towns: clusters of buildings, narrow alleys, and streets.

Multiple structures are visible in the dataset, and in some places, details suggest the presence of two-room dwellings with corner hearths.

The GPR results show clusters of buildings, narrow passageways, and street alignments typically for Norwegian medieval towns. The data has now been confirmed. (Photo: Jani Causevic / NIKU / GPR image: Monica Kristiansen / NIKU)

Research excavation to confirm the GPR results

A research excavation, funded by Anno Museum, was initiated to determine whether the features seen in the radar images were indeed the remains of the medieval town of Hamarkaupangen.

The excavation aims to investigate one of the presumed structures identified in the 2023 GPR data.

Beneath an one-metre-thick layer of cooking stones, archaeologists are now uncovering timber remains – walls and floorboards – that confirm the radar showed timber buildings.

The structure in question, interpreted from the data as a two-room dwelling, has timber walls and plank flooring from multiple construction phases. The team is now searching for a hearth.

A glimpse of a lost town

Although only a small part of the structure was uncovered, it plays an important role in understanding the larger town layout seen in the radar data.

These findings strongly reinforce the theory that Hamarkaupangen had timber buildings arranged like a town.

The coming weeks may bring further discoveries, and potentially dating evidence, to clarify the historical context of the site.

A sample of the timber has been sent to Uppsala, Sweden for radiocarbon dating. The archaeologists expect results next week.

Small excavation with big results

Archaeologist Monica Kristiansen, who interpreted the radar results, expressed both excitement and caution:

“We were eager to see what lay below ground. The thick layers of cooking stones presented a new context for us. We had no prior experience of how these stone-filled layers might affect the visibility of wooden structures in the GPR data," she says.

Kristiansen adds that preservation conditions for organic materials in this area are generally poor, so the researchers expected the remains of the timber buildings to be in poor condition.

"It's therefore extremely encouraging that the radar interpretations are being confirmed,” she says.

The excavated area covers only four square metres, yet it has already yielded significant results in the search for Hamarkaupangen.

The archaeologists have confirmed both wall timbers and flooring, which bodes well for future investigations of the rest of the field.

The layer of cooking stones at the excavation site is up to one metre thick, making the work physically demanding. Yet beneath this stone layer, traces of a long hidden medieval town are beginning to re-emerge.

It is a true testament to the power of geophysical methods, patient investigation, and the enduring questions posed about Norway’s medieval past.

This content is paid for and presented by NIKU - Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research

This content is created by NIKU's communication staff, who use this platform to communicate science and share results from research with the public. NIKU is one of more than 80 owners of ScienceNorway.no. Read more here.

More content from NIKU:

-

Archaeologists debunk period myths from the Middle Ages

-

Swedish King Charles XII transported massive ships overland to attack a Norwegian fortress. Researchers have now uncovered the forgotten route

-

According to an Old Norse saga, a man was thrown into a well in 1197 to poison the water. Researchers can now reveal more about who he was

-

This robot is on the hunt for Norway's hidden cultural heritage

-

Promising results with ground-penetrating radar in Iceland

-

The Gjellestad burial mound belonged to the Iron Age elite