THIS CONTENT IS BROUGHT TO YOU BY SINTEF - read more

How researchers plan to prevent plastic pollution in the ocean

Ropes and equipment used in fishing and aquaculture are a major source of microplastics in the ocean and litter along the coastline. A research team now has a plan to reduce this pollution.

You may have seen images of seabirds that have built their nests on discarded nets, lengths of rope, and other plastic waste. Or birds with stomachs full of microplastics.

There is also an invisible and very harmful effect of discarded fishing gear, known as ghost fishing. Abandoned traps and nets can continue to catch marine life almost indefinitely.

This pollution has major consequences for life in and around the ocean.

It may be invisible, but it is still a huge problem

Other fishing gear, ropes, and microplastics sink to the seabed, creating an invisible problem. A nylon line can last up to 600 years on the seabed. This gear is mostly made from non-degradable plastics such as polyethylene, polypropylene, polyester, and polyamide.

Researchers are now seeking to develop new materials that break down faster without causing pollution.

“Fishing gear remains in situ for a long time and, in practice, turns the ocean into a plastic landfill site, because particles of microplastics are formed when the materials degrade in the ocean," explains researcher Christian Karl from SINTEF.

The problem of lost fishing gear and equipment from the aquaculture industry is enormous. Most of it is made of plastic.

Fortunately, the Norwegian Directorate of Fisheries conducts annual voyages to search for lost nets and other fishing gear in areas where losses have been reported.

Researchers are working hard to find and test alternatives to plastic materials that either last 'indefinitely' or break down into micro- and nanoplastics.

In particular, the use of bottom trawling and Danish seine fishing is leading to large quantities of microplastics ending up in the ocean.

“We have already come a long way in the work,” says Karl.

He is a polymer chemist and specialises in material combinations in plastic, degradable alternatives, and material analysis. For almost four years, he and colleagues both in Norway and abroad have been working to find solutions to the problem.

Karl has been responsible for testing the biodegradability and environmental impact of fishing gear in the Dsolve project. Here, researchers are examining biodegradation in different marine habitats and climate zones, including Skagerrak, the North Sea, the Baltic Sea, the Adriatic Sea, and the Norwegian Sea.

The tests are conducted at temperatures ranging from 4 to 27 degrees Celsius. The aim is to compare how biodegradable and conventional gear cope:

“The tests will continue for at least three years or until the materials have completely degraded. We will study microbiological, UV, thermal, and chemical degradation in detail,” the researcher explains.

The tip of an iceberg

One of the partners in the project is the Norwegian College of Fishery Science at UiT The Arctic University of Norway. Among those working there is Professor Roger Larsen, who began his professional career as a fisherman. He is now working with SINTEF to find solutions to the problem through Dsolve, where he is centre manager.

The goal is to develop new degradable materials that can replace the current plastic materials used in fishing and aquaculture equipment – without turning into microplastics.

“Specialists from the Directorate of Fisheries are very knowledgeable and ensure that large quantities of discarded fishing gear are collected every year. Virtually everything is made of plastic,” says Larsen.

“But there are some unknown figures, too: In 2022, for example, no less than 40 kilometres of Danish seine rope was recovered. This rope was found by chance and had not been reported as lost fishing gear,” he adds.

The researchers' vision is to reduce both ghost fishing and plastic pollution. This will be carried out in collaboration with industry, universities, research institutions, and advocacy organisations. They have now identified what needs to be done.

The researchers suggest four main steps to address the problem:

- Develop biodegradable ropes and fishing gear as an alternative to ordinary oil-based plastics.

- Develop new fishing gear with simpler designs to make recycling easier.

- Contribute to the industrial upscaling of solutions.

- Ensure that materials can be recycled.

The research has been conducted in collaboration with partners in Denmark, Germany, Croatia, and South Korea. It has also led to field trials in countries such as the USA, India, and China.

A complicated puzzle

The research team has tested and experimented with the degradation of alternative materials.

In practice, this means that they have looked at the mechanical properties and wear of the materials.

Karl explains that if we are to eliminate everlasting fishing gear and the pollution it causes, materials must be biodegradable – but still strong enough to do the job.

“An important aim is therefore to develop materials and fishing gear that are user-friendly during what we call the service period, but then degrade rapidly,” he says.

his is no simple task, as the materials can concist of different components. Some even contain a core of steel, lead, or are impregnated with copper.

To make plastic production in the fishing and aquaculture sectors more sustainable and circular, it is important to cooperate across sectors and disciplines, according to Karl.

“In this way, we can solve global problems at a local level. Little by little, steady progress is being made in overcoming the challenges associated with the quality of recycled materials, or the removal of copper from fishing gear, to mention just a few problems," he says.

Currently, one of the challenges is that fishing gear is made from many different types of materials. This makes it difficult, and sometimes even impossible, to recycle materials in a way which ensures that the value of the materials in their future life remains sufficiently high.

“We are working on this in another project called SHIFT plastics,” adds the researcher.

Ready-to-use results

So far, researchers have succeeded in finding sustainable solutions for many different types of fishing gear, but not all:

“As regards degradable fishing nets, we currently have fishing gear that delivers on 70 per cent of the properties,” says researcher Roger Larsen.

That is why the team is still searching for the perfect combination of materials. Nets are one of the biggest challenges. The mesh must be thin and invisible to the fish, yet strong and elastic enough to function as well as nylon in practice.

However, for longline fishing gear, researchers have demonstrated that there is no significant difference in catch efficiency when nylon is used compared to a biodegradable alternative.

In modern mechanised line fishing (autoline), a single longline can stretch up to 90 kilometres, with up to 70,000 hooks attached by short half-metre-long lines.

Larsen explains that these shorter lines, called gangions, can wear out, break, and get lost in the thousands every year – just in Norway alone.

“Today, gangions are made of polyester or nylon, which are very strong materials that sink and end up on the seabed, where they can take a very long time to break down,” he says.

“In the case of coastal line fishing, shorter line lengths are used, but even vessels 11-15 mtres in length can use lines with up to 30,000 hooks,” explains the former fisherman.

But, there is hope:

“We have conducted tests that show there is little difference in catch efficiency when degradable materials are used. We have a biodegradable alternative that will dissolve within a few years, without leaving any microplastics behind,” says Larsen.

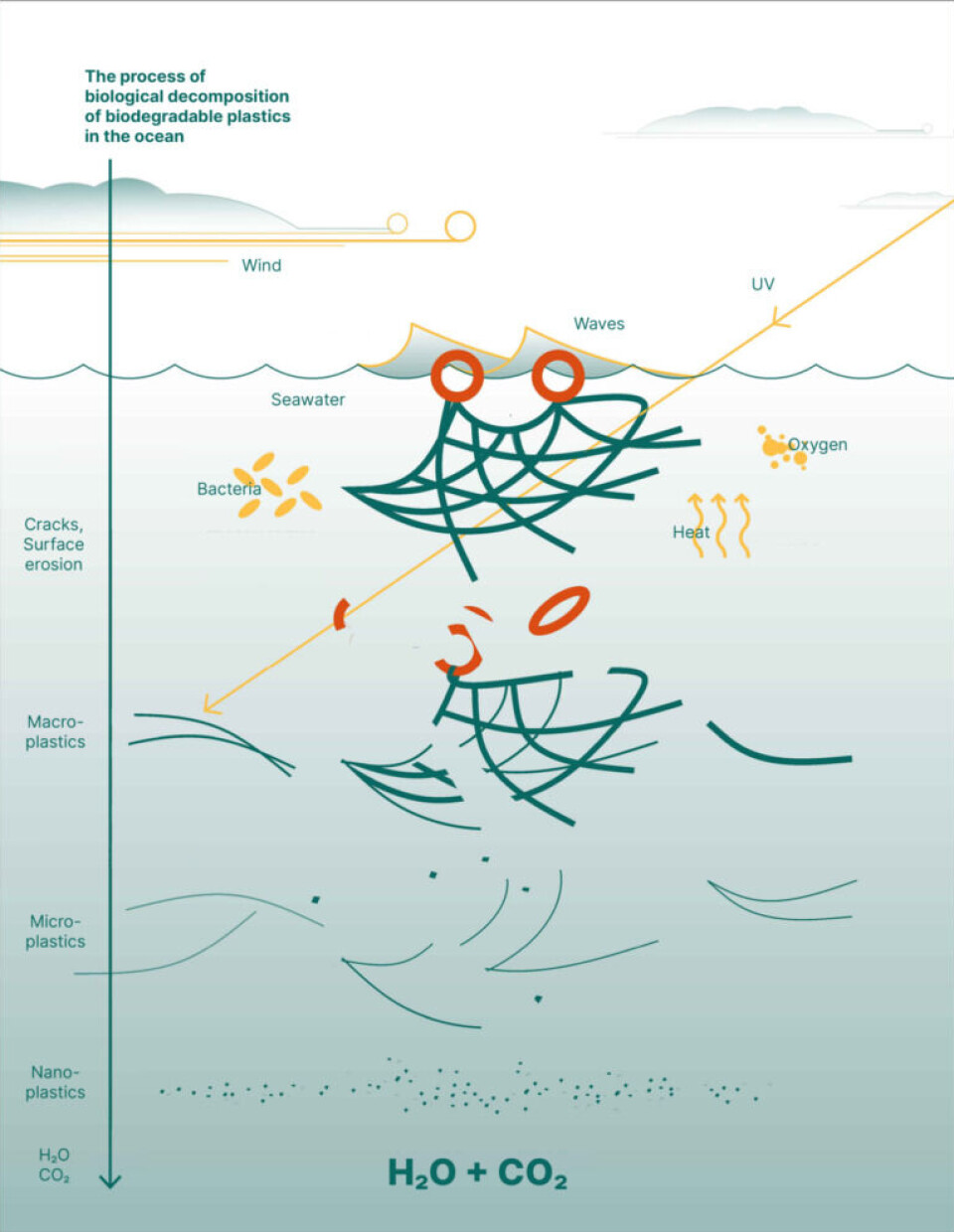

How long the degradation process takes will depend on many factors, including temperature, light, and microbial activity.

“However, what we can guarantee is that the materials will have a ‘life in the ocean’ of much less than several hundred years, which is what the Norwegian Environment Agency estimates the lifespan of an ordinary nylon line to be,” he says.

The harmful impact of bottom trawling

Two of the worst culprits are bottom trawling and Danish seine fishing. The dragging of the fishing gear along the seabed causes extensive wear on the materials. The nets used in wings, bags, and trawls have attracted criticism – the lifespan of the fishing gear is relatively short.

The discarded remains can also end up on our beaches and in the stomachs of seabirds.

This happens because the materials float to the surface, where their tempting colours can be mistaken for krill and other prey. Some of this plastic litter also gets used as nesting material by birds.

Researchers are also exploring environmentally friendly alternative materials that can be broken down by nature itself.

“This is especially true as regards the wear mat which is placed beneath the trawl net itself and provides protection to prevent holes from being created by wear and tear, causing the catch to be lost,” says Larsen.

The bio-polyester material may also be suitable for use in Danish seine fishing, especially for the rope arms that guide the fish into the net.

However, this alternative is a relatively expensive investment in the short term:

“It soon becomes too expensive for fishermen with small quotas, so we need to find cheaper solutions, such as wood fibre, animal hide, or cotton. What we do know has worked well as slaughter mats/chafe mats in bottom trawling ever since ancient times is cowhide,” says Larsen.

In the Netherlands, researchers have successfully tested the hides of Yak bulls. However, finding the right supplier and quality is crucial before such animals can once again be used in fishing gear.

“We know the solutions exist. We just have to crack the code at material level, based on the development of materials and properties linked to degradation,” says Christian Karl at SINTEF.

References:

Dsolve: Annual Report 2022

Grimaldo et al. Reducing plastic pollution caused by demersal fisheries, Marine Pollution Bulletin, vol. 196, 2023. DOI: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2023.115634

Palmer et al. Enabling transition thinking on complex issues (wicked problems): A framework for future circular economic transitions of plastic management in the Norwegian fisheries and aquaculture sectors, Journal of Cleaner Production,vol. 449, 2024. DOI: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.141420

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

More content from SINTEF:

-

Saving seagrass and French oysters: New solutions give new life to Europe's coastal areas

-

What does ultra-processed food do to our gut flora?

-

This new device can make it cheaper to heat your home

-

Propellers that rotate in opposite directions can be good news for large ships

-

How Svalbard is becoming a living lab for marine restoration

-

New study: Even brand-new apartments in cities can have poor indoor air quality