An article from University of Oslo

X-ray chemist solves cholera mystery

How ill you get from cholera depends on your blood group. A new remedy for the feared illness can be found by studying the molecular structure in the toxin in the cholera bacteria.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

Three to five million people are infected by cholera ever year. The mortality rate is high: one hundred thousand people die from the feared illness every year.

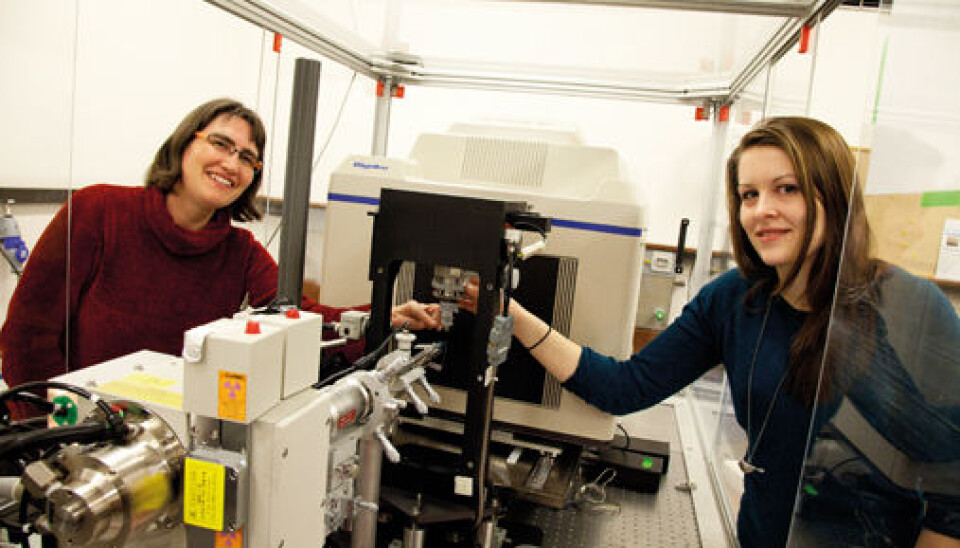

"Cholera depends on the blood group. Some blood groups have an increased risk of becoming seriously ill", says Professor Ute Krengel in the Department of Chemistry at the University of Oslo.

When cholera bacteria multiply in the body, they create an awful toxin called cholera toxin. The toxin must bind to the cell membrane before it can penetrate further into the intestinal cell and create trouble.

By studying the molecular structure of cholera toxins, researchers can discover how the toxins bind to intestinal cells at the level of the atom.

Krengel's goal is to find a new medicine that prevents the cholera toxin from binding to the intestine and that ensures that the toxin is harmlessly dispelled from the body.

Cholera leads to violent diarrhoea. The patient can lose up to 12 litres of fluids every 24 hours. The treatment is a saline fluid replacement.

"It must be administered as soon as possible and in large quantities. If the patient is unconscious already, the saline solution must be given intravenously. Antibiotics are of no use", explains Professor Gunnar Bjune in the Institute of Health and Society at the University of Oslo.

Blood group O is the worst

The cholera bacterium is originally from Bangladesh, but in the past two centuries, it has spread to much of the world and has established a firm footing in many Asian and African countries.

"Patients with blood group O are most at risk of becoming seriously ill. Those with blood groups A, B or AB are more protected against cholera", says Ute Krengel.

The Bangladeshi population is evenly distributed between blood groups O, A and B. In Africa, most people have blood group O. Nearly everyone in the indigenous population in Latin America have group O. When cholera hits these areas, it hits especially hard.

In collaboration with the Oslo University Hospital and the Biotechnology Centre, Ute Krengel's research group studies whether the probability of becoming seriously ill with cholera depends on blood groups.

By studying the molecular structure in the toxin in the cholera bacterium, it is possible to find a new remedy for the feared illness, determine how strongly the cholera toxin binds, how long it takes to bind, and how long it stays bound to receptors on the intestinal cells.

Fools the bacteria

The cholera toxin binds to small receptors on the intestinal wall. The receptors consist of small straws with attached sugar molecules. They are to protect the cells against harmful intruders Unfortunately, the receptors can be exploited.

"We want to develop new medicines that bind to the cholera toxin so that it cannot bind to the intestinal cells."

The cholera toxin consists of two parts. The researchers study the lower part, which binds to the receptors.

"We have discovered that the cholera toxin binds differently than previously thought."

The toxin is a protein. Proteins are built from amino acids. The Krengel group will now study how important the various amino acids are in the binding process and which amino acids bind the most.

In order to penetrate into the intestinal cells, the cholera toxin must first get through mucous layer.

"Our results suggest that the cholera toxin uses longer to penetrate the mucous layer if the patients have blood group antibodies in the mucous. Four out of five people have blood group antibodies in the mucous. Those with blood group O are the least protected and therefore get sicker than others."

Harmless cholera model

In its advanced experiments, the Krengel group has created a biological model of how the cholera toxin enters intestinal cells. They do not use real cholera bacteria. Doing so would be too dangerous. Instead, they use E.coli bacteria, which is the primary model bacterium for cell biologists.

"They are easy to make and much quicker and safer to work with. We must grow large quantities in order to study the bindings", says PhD Candidate Julie Heggelund, whose background is in molecular biology.

To create artificial cholera toxins–or to be precise: to create the lower part of the toxin–she must manipulate the genes in E. coli bacteria. When she has produced the lower part, she kills the bacteria in a pressure cooker. The receptors are synthetic sugar molecules.

X-ray control

Microscopes are of no use in finding the structure of the cholera toxin and receptors: the resolution is not good enough. Researchers must rely on x-rays. X-rays have such a short wavelength that most penetrate empty space in molecules. However, before they can get started with the x-ray machine, the researchers must crystallise the toxin and receptor molecules. This is Krengel's speciality.

By interpreting the x-rays that are spread by the crystal, researchers can calculate what the structure of the atom looks like. This can be compared to sending laser light through a sieve. Studying the light that is spread by the mesh of the sieve allows researchers to calculate what the sieve looks like.

Each exposure is two-dimensional. To create a three-dimensional image, researchers irradiate the toxin crystal up to 500 times from different angles. Though the imaging only takes a few days, the interpretation of the molecular structure can take several months.

Julie Heggelund also takes such x-ray images in Grenoble. Thanks to a large x-ray machine with a circumference of nearly one kilometre, the imaging can be done in as little as two minutes.