THIS ARTICLE/PRESS RELEASE IS PAID FOR AND PRESENTED BY Fridtjof Nansen Institute - READ MORE

Norway has the strictest aquaculture regulations in the world. Will other countries follow suit?

Researchers see big differences in the regulation of fish farming industries in countries that have wild salmon.

Is sustainable aquaculture possible? Researchers at the Fridtjof Nansen Institute (FNI) have compared the regulations in countries that have stocks of wild salmon.

We still lack a comprehensive scientific basis for determining the precise extent of the effect of salmon lice (Lepeophtheirus salmonis) on wild salmon stocks. In Norway, the industry and the authorities agree that salmon lice in fish farms can affect the mortality of wild salmon as well.

Therefore, Norway has extremely strict regulations for the permitted number of lice per fish in fish farms. During the sensitive period when the young wild salmon (smolt) swim out from Norwegian rivers and into the Atlantic, a maximum average of 0.2 female lice per fish in Norwegian fish farms is allowed.

However, this upper limit is based not on scientific certainty about the effects of various thresholds on wild salmon, but on pragmatic considerations and the precautionary principle.

It is known that the wild salmon are affected, but not the extent of the impact, and that is why Norway has such strict limitations.

Stricter international regulations

And yet, there exists an even stricter regime: the international certification programme for responsible aquaculture, of the Aquaculture Stewardship Council (ASC). By committing to ASC regulations, aquaculture managers can become qualified to use the ASC label, which shows consumers that the salmon comes from fish farms that have minimised their effect on the environment.

"ASC wishes to be the golden standard for environmentally responsible salmon farming in the world," senior researcher Irja Vormedal explains. She is involved in an FNI research programme to quantify fish farms on various indicators. Together with research colleague Mari Lie Larsen, she has prepared an evaluation that compares the indicator for the average number of salmon lice per fish in fish farms across several countries that have both aquaculture and wild salmon stocks.

A requirement that cannot be met

"According to ASC’s requirements, more than 0.1 lice per fish cannot be allowed in the sensitive period in fish farms. This requirement is very strict, however, and ASC is now considering moving away from it," Vormedal explains.

It is in connection with such revision of the certification programme that Vormedal and colleagues have done their research.

"Few aquaculture managers in the world today can meet the requirement of maximum 0.1 female lice per farmed fish" she says. "Many apply for exemption from this requirement because it is so hard to meet."

Vormedal and colleagues have compared the salmon lice regulations in several fish-farming countries that also have wild salmon populations.

"We evaluated how these countries regulate and deal with salmon lice. We found that Norway has the unquestionably strictest regime of all," she says.

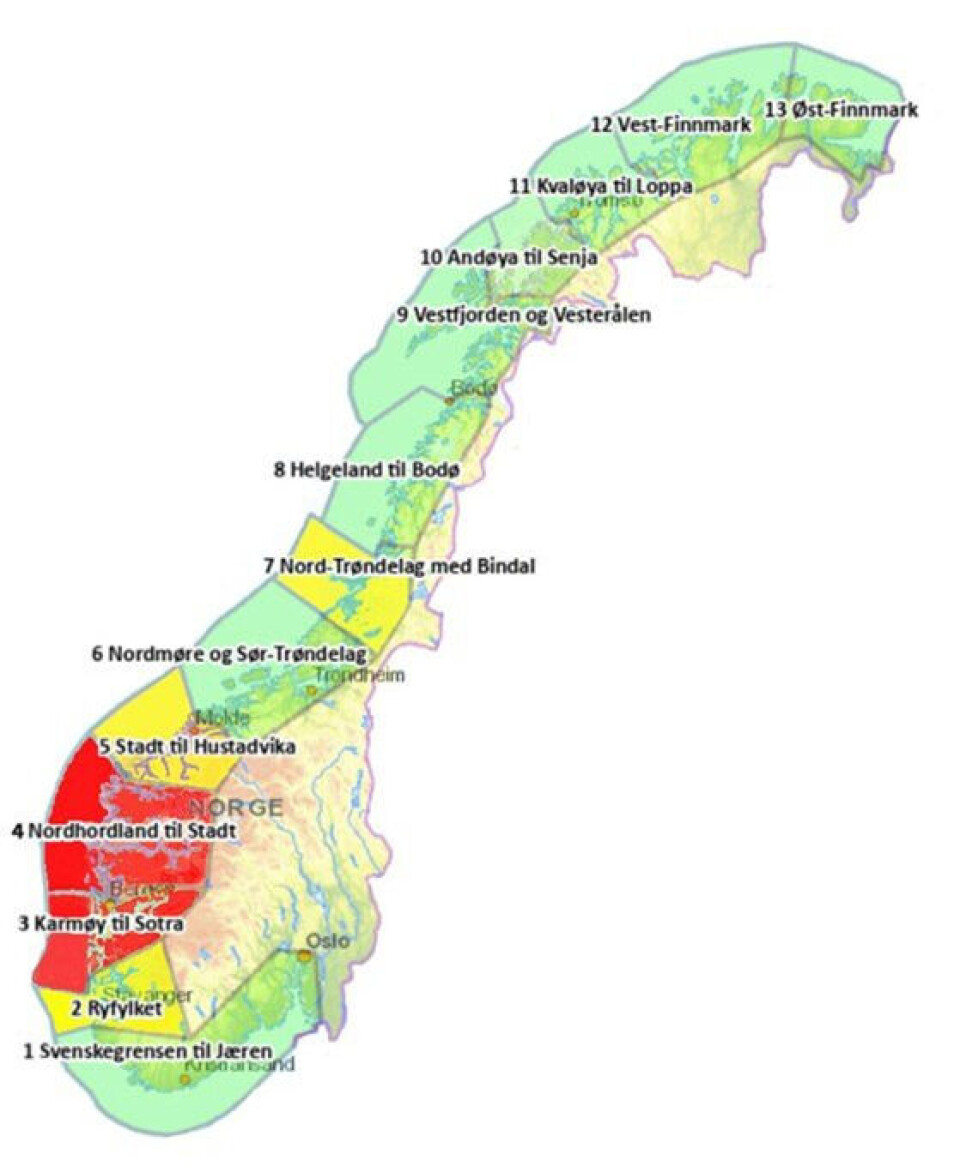

The Norwegian coast is divided into thirteen salmon production regions or areas. Vormedal explains that Norway has both the strictest limit value for the number of lice per fish, as well as a ‘traffic light’ system which regulates the total amount of fish allowed in a production area, on the basis of risk estimates for wild fish mortality as a result of salmon lice from fish farms.

A production area’s colour in this traffic light system is set on the basis of estimates of high, moderate, or low risk of salmon lice leading to greater mortality among wild salmon in the area. In turn, this determines whether aquaculture managers in a given area are allowed to increase their production capacity. If they are given the red light, they must reduce production capacity by six per cent.

Nature versus nurture

"There are many stakeholders when it comes to aquaculture and regulations. It was the WWF and IDH (the Dutch Sustainable Trade Initiative) that initiated negotiations concerning private regulation of aquaculture through the ASC standard. In practice, what is feasible for the industry and what we need to do to protect nature – specifically, the living conditions and population development of wild salmon – are set up against each other," Vormedal says.

She explains that there are many influencing factors and they can be shifting, so measuring the degree of influence of individual factors can be difficult.

"The survival rate of Atlantic salmonids is less than ten per cent, and the majority of wild salmonids die at sea for various reasons. Quantifying how much of this mortality is due to salmon lice is not easy. For example, climate change leads to warmer seas, which could also affect wild salmon survival," Vormedal says. "We find interesting differences among the countries we have examined. Norway is far stricter than the others, with its limit of 0.2 lice per fish in the sensitive area. In addition comes the traffic light system which regulates the total amount of fish in entire regions, called 'production areas’."

Agreement and controversy

"We have found major differences among countries as to where and how they set the limit values," Vormedal says, noting that there is considerable controversy over whether salmon lice negatively affect wild salmonids.

"In Norway, the authorities assume that the wild salmonid stocks are threatened by salmon lice infections. In some countries, however, there is a state of impasse, even between different government agencies. The authorities in Canada (British Columbia) and in Ireland hold that the negative effects of salmon lice infection on wild salmonids have not been scientifically proven, so they do not regulate it strictly," she says.

Internationally, there is still scientific uncertainty and disagreement regarding the degree of influence of salmon lice on population levels, but laboratory tests have shown that salmon lice do have a negative effect on individual fish.

"What is certain is that the fish are negatively affected by salmon lice. Among other things, the lice cause damage which makes the salmon more susceptible to other infections; stress levels can increase, and swimming skills can be reduced. We must also weigh the pros and cons of cleaning live farmed fish of lice. These cleansing processes are very stressful for the farmed salmon, and we need to find out how to balance the disadvantages," Vormedal explains.

Canada (BC): a state of impasse

Vormedal and her colleagues have interviewed central figures in many fish-farming countries. In contrast to Norway, Canada (BC) does not have Atlantic salmon, but is home to the Pacific pink (or humpback) salmon (Oncorhynchus gorbuscha).

The Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO), a department of the national government, is responsible for regulating fisheries in the country. They hold that because Norway and Canada have different varieties of salmon, they cannot be compared.

"DFO researchers strongly believe that salmon lice cannot explain the decline in wild salmon stocks," Vormedal says. "They consider their current regulation of 3.0 mobile lice per farmed fish (which corresponds to about 0.9 female lice) is sufficient. On the other side there are exasperated wild salmon advocates and scientists who dismiss the current regulatory system as a joke."

Ireland: No agreement

There is no scientific consensus on the matter in Ireland either.

"The Marine Institute (MI), which monitors and regulates marine life in Ireland, is well staffed with researchers. They believe that there is no evidence that salmon lice have any population-regulating effects, i.e., that salmon lice affect the mortality of the wild salmon," Vormedal says.

By contrast, Inland Fisheries Ireland, under a different department, is more focused on nature conservation and environmental concerns.

"They are responsible for the wild salmon and believe that the MI researchers are wrong. The government develops its regulations on the basis of MI’s conclusions. In Ireland, the limit for the number of lice per farmed fish is 0.5, but this is a trigger level. The government believes this limit to be strict enough and that sufficient consideration is given to the wild salmon," she says.

Further, Vormedal notes that it is easier to compare Norwegian conditions with Ireland, as both countries have the same type of wild salmon. However, Ireland has a far smaller farming industry than Norway, and it is difficult to get permission to start new fish farms there.

"The Norwegian-based multinational company MOWI recently acquired a new, organic fish farm in Ireland. It took them 10 years to get their application approved – and that was the first new farming permit granted in 17 years," she says.

Scotland: No regulations

Scotland has not had any regulations relating to the conservation of wild salmon stocks until now. Salmon lice have been regulated, but not because of the need to protect the wild salmon. Scotland has kept the salmon lice levels low for considerations of the health of farmed salmon. The Fish Health Inspectorate (FHI) is responsible for inspections.

"This is about fish health, not environmental concerns, and the regulations have been quite lax," Vormedal explains, noting that the limit for the number of lice per fish was set at a whopping 2.0.

"That is a so-called trigger level. If aquaculture managers exceed this level, authorities get involved and begin to consider whether measures are needed," she says.

Vormedal also points out that Scotland has not introduced a ‘sensitive period’ covering the time when the wild smolt swim out into the sea.

"However," she adds, "there has been a big political debate around aquaculture in the past few years. All the environmental movements in Scotland are on the alert. There have been several major parliamentary debates on the issue, and the authorities have set up working groups which have produced new recommendations."

Scotland looks to Norway

"It looks as if Scotland will base much of its new policies on what we have done in Norway. They are going to reform the entire system – it may be that Scotland is moving towards a kind of traffic light system. They will assess the totality of the infection pressure from lice in entire areas and regulate the total amount of farmed fish based on the mortality risk for wild salmon," Vormedal says.

According to her, there is a greater degree of scientific consensus in Scotland than in Ireland and Canada. They also lean quite heavily on Norwegian research, as they have little of their own.

The Faroe Islands: The industry needs regulations

The Faroe Islands are quite unique. They have no salmon rivers, only migrating wild salmon from other countries which graze in the waters around the islands. However, the Faroes have some sea trout in their rivers, and the government has now begun to investigate whether some protection is needed here.

Due to sea currents round the Faroes, the salmon lice spread easily from farm to farms. However, aquaculture managers feel that it is both important and profitable to keep the lice levels low.

The Faroe Islands have now implemented a fixed limit of a maximum of 0.5 lice per farmed fish. Moreover, they now have directions for the sensitive period as well.

"The interesting thing about the Faroe Islands is that the demand for regulations has come from the aquaculture industry. And the introduction of a sensitive period came because many in the industry committed to the ASC standard," Vormedal explains.

In order to meet the requirement of 0.1 lice, the industry was dependent on having a sensitive period introduced by the authorities.

"It remains to be seen whether the Faroe mindset – that it is profitable to keep salmon lice levels low – will affect others in the aquaculture industry. This will be exciting to see," Vormedal concludes.

Reference:

I. Vormedal and M.L. Larsen. Regulatory Processes for Setting Sensitive-Period Sea-lice Thresholds in Major Salmon Producer Jurisdictions: An Evaluation, The Fridtjof Nansen Institute (FNI) report, 2021.

This article/press release is paid for and presented by Fridtjof Nansen Institute

This content is created by Fridtjof Nansen Institute's communication staff, who use this platform to communicate science and share results from research with the public. The Fridtjof Nansen Institute is one of more than 80 owners of ScienceNorway.no. Read more.

See more content from Fridtjof Nansen Institute:

-

“It's been a long time since we've seen so many positive developments in such a short period. We may indeed be entering a turning point for nature”

-

Russia could lose its big chance in the global gas market

-

Russia pushes for a fossil economy. Can China stop them?

-

What does China aim to gain in the Arctic?

-

Where do the metals in your electric car come from?

-

Power struggle in the Arctic Council: Greenland demands a leading role