THIS ARTICLE/PRESS RELEASE IS PAID FOR AND PRESENTED BY the Institute of Marine Research - read more

Researchers found too many worms to count inside stranded whales - this is good news

It means that despite massive human impact to nature, the conditions to maintain the worm’s complex life cycle hold.

“Whales are the endgame for Anisakis parasites, often called kveis or whale worms,” researcher Paolo Cipriani says. “While we often find them in the flesh or gut of fish, this is most likely just a means of transport to reach marine mammals, their definitive host."

Whales are the first and final stage of a complex cycle

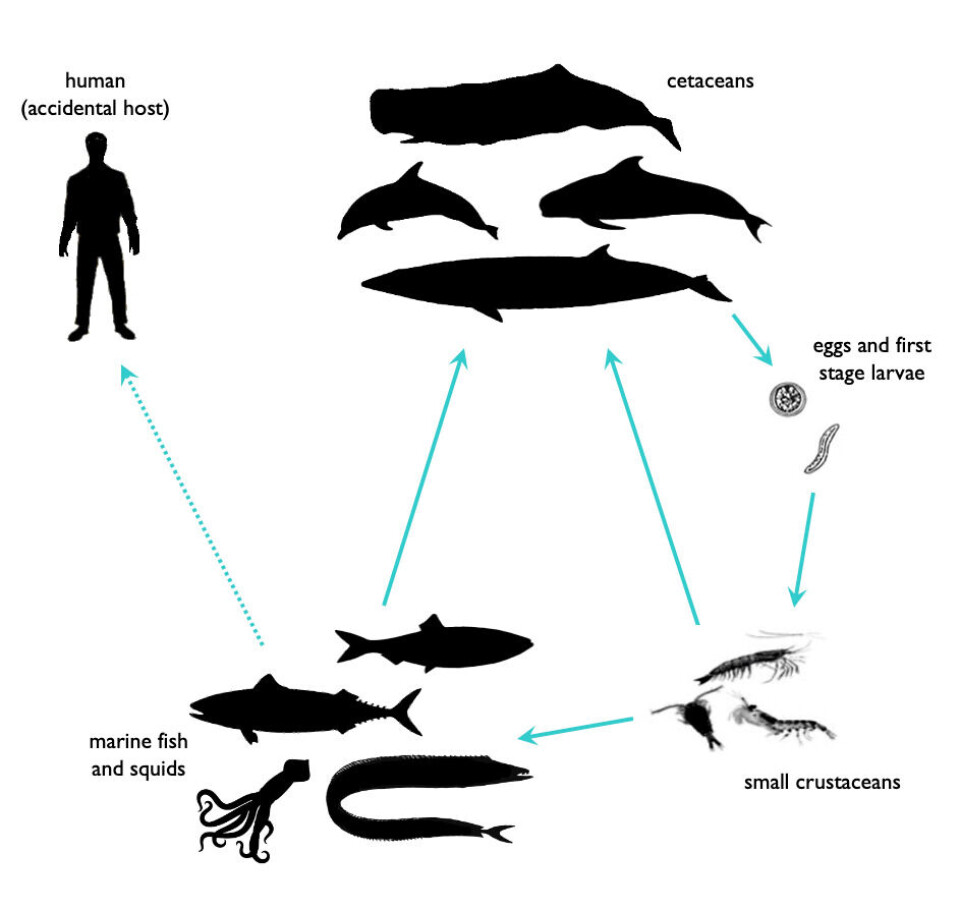

In cetaceans (whales, dolphins and porpoises), Anisakis develop and transform, mature, mate, and produce thousands of eggs, closing its complex life cycle inside a chain of host organisms.

The eggs are expelled through feces, hatch, larvae are eaten by crustaceans which are then eaten by fish. Cetaceans are the apex predators and final stage.

Found a wide range of both whales and their worms

In a study recently published in Scientific Reports, researchers from the Institute of Marine Research (IMR) and La Sapienza University of Rome, together with several other European collaborators in the field, examined the stomach contents of 34 stranded cetaceans, looking for parasites.

In most cases, the mammals were full of worms to the extent that it was impossible to count or estimate the total infection. We are talking thousands.

In whales, the worms are only found inside the digestive system. They are not able to enter the meat and risk infecting whale-consuming humans by accident.

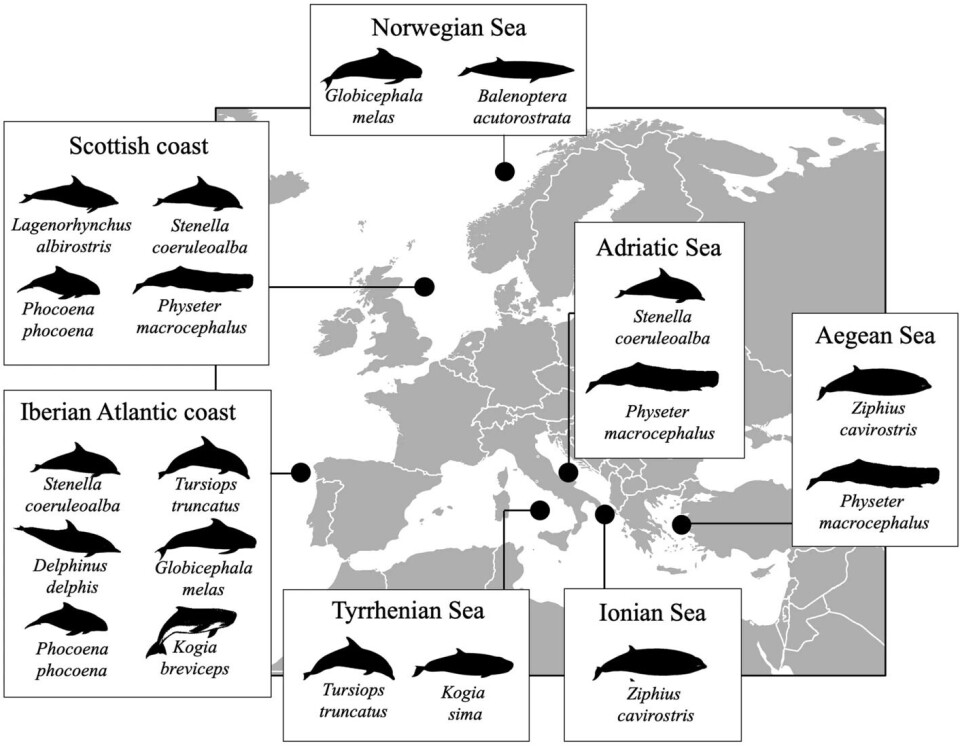

The researchers genetically analysed hundreds worms from 11 cetaceans species, including harbour porpoises, dolphins, baleen whales and sperm whales.

The animals were stranded along the European coast of the Northeast Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea (including Norway, Faroe Islands, Scotland, Spain, Italy, and Greece).

Reseachers now know the worms’ preferences and distribution

“We genetically identified the worms, which belonged to five species, and found a clear pattern of their geographical distribution and host preference,” Cipriani says.

The Anisakis species showed a preference for certain cetacean groups: Anisakis simplex, common in the Norwegian waters, is a generalist in both fish transport and definitive host, preferring dolphins and baleen whales.

Other species, like A. physeteris, is only found in in sperm whales and pygmy sperm whales.

Cipriani explains this by natural selection and millions of years of co-evolution and co-adaption. The 'correct' parasite make it to the specific definitive host.

Shows that the food webs are intact

Researcher Cipriani is happy to have found such a large diversity of Anisakis.

“The stable presence of these parasites in the food webs of northern ecosystems are paradoxically good news," he says. "Despite massive human impact to nature, the conditions to maintain the worm’s complex life cycle hold. This indicates that the food chain and a part of the ecosystem is stable, and that whale populations are recovering from the 18th century indiscriminate whaling."

The novel baseline research also lets the researchers look for changes in the future.

How the IMR looks for Anisakis

The IMR already has a continuous surveillance of presence of parasites in fish, as this is a consumer concern.

To follow up on the mammals, the parasite researchers have recently started a cooperation with the marine mammal group at the IMR. They will look at cetaceans and also seals, as they are the definitive host and home for other anisakid species typical of northern waters.

Reference:

Cipriani et al. Distribution and genetic diversity of Anisakis spp. in cetaceans from the Northeast Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea, Scientific Reports, vol. 12, 2022. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-022-17710-1

This article/press release is paid for and presented by the Institute of Marine Research

This content is created by the Institute of Marine Research's communication staff, who use this platform to communicate science and share results from research with the public. The Institute of Marine Research is one of more than 80 owners of ScienceNorway.no. Read more here.

See more content from the Institute of Marine Research:

-

Do whales compete with fishermen?

-

These whales have summer jobs as ocean fertilisers

-

Have researchers found the world’s first bamboo coral reef?

-

Herring suffered collective memory loss and forgot about their spawning ground

-

Researchers found 1,580 different bacteria in Bergen's sewage. They are all resistant to antibiotics

-

For the first time, marine researchers have remotely controlled an unmanned vessel from the control room in Bergen