THIS CONTENT IS BROUGHT TO YOU BY the University of Bergen - read more

Book fragments from the Middle Ages were preserved by chance

In the Nordic countries, tens of thousands of pages from liturgical books from the Middle Ages have been preserved.

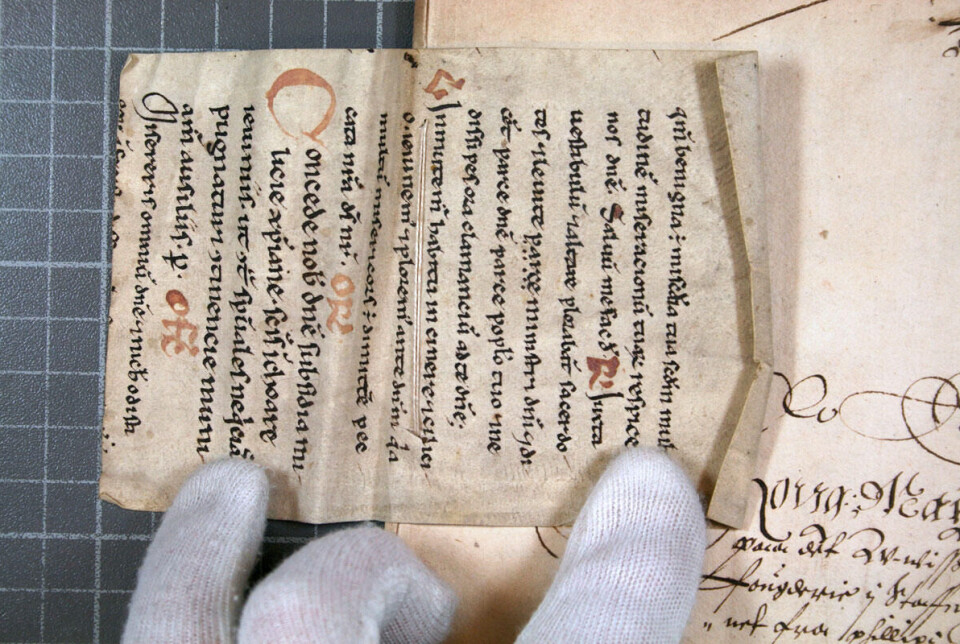

The National Library of Finland’s Fragmenta Membranea collection includes around 9,300 parchment leaves from around 1,500 manuscripts from the Middle Ages. Most of these are liturgical books that were used in churches.

Catholic missals became unnecessary with the Reformation, but from the 1530s onwards, a new use was found for their sturdy and durable material as covers for account books used by bailiffs.

In the Kingdom of Sweden, all tax administration documents were archived in Stockholm, but in 1809, when Russia annexed Finland, materials pertaining to Finland were moved to Finland – and with them, thousands of leaves from medieval manuscripts as their covers.

The bailiff's accounts are kept in the National Archives of Finland, but their covers were formed into a collection that is kept at the National Library of Finland.

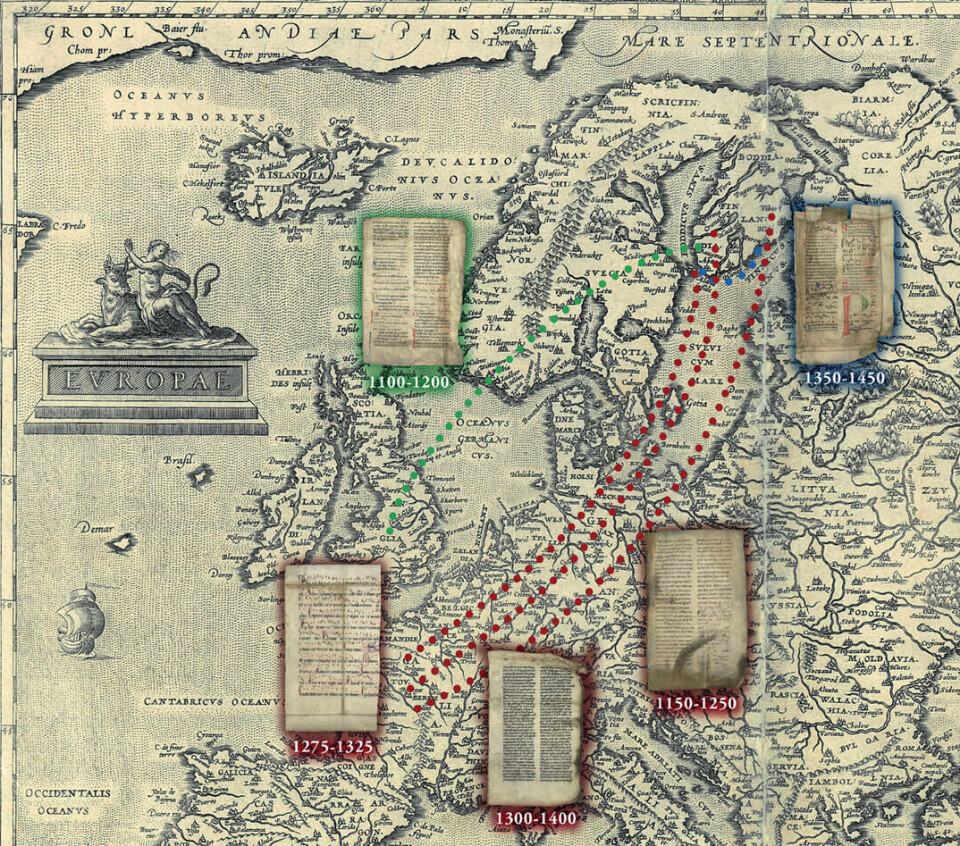

"Fragments belonging to the same book have been scattered around Finland and Sweden, and sometimes Denmark and Norway as well," Jaakko Tahkokallio says. He is a senior researcher at the National Library of Finland, and leads the research project focused on the collection.

In Norway, which was a part of Denmark back then, the practices for the same kinds of materials were similar. With around 40,000 parchment leaves, the collection in Stockholm is the largest of these. Finland and Norway have focused most on researching the fragments.

"In Sweden, for example, there is much more to explore for those interested in medieval manuscripts," Åslaug Ommundsen says.

She is a professor of Medieval Latin Philology at the University of Bergen.

"Finland and Norway are in the same boat in the sense that very fewcomplete manuscripts have been preserved, and therefore the collection of fragments has attracted more interest," she says.

A puzzle with tens of thousands of pieces

Åslaug Ommundsen is one of the central figures in Nordic fragment research, as she has focused on the research of this material for two decades.

During her master's phase, she studied medieval manuscripts in the Vatican Library, but after that she wanted to find local material to study.

"I asked a professor in Oslo what he would recommend, but he said that no medieval books in Latin have survived in Norway. Later, I found out by chance that they do exist – they're just in thousands of loose pieces," she says.

Ommundsen became interested in the material immediately, and after getting to know it in more detail, she was sold.

"As source material, the collection of fragments is fascinating and versatile – we just have to try to put the puzzle together to get to the bottom of it."

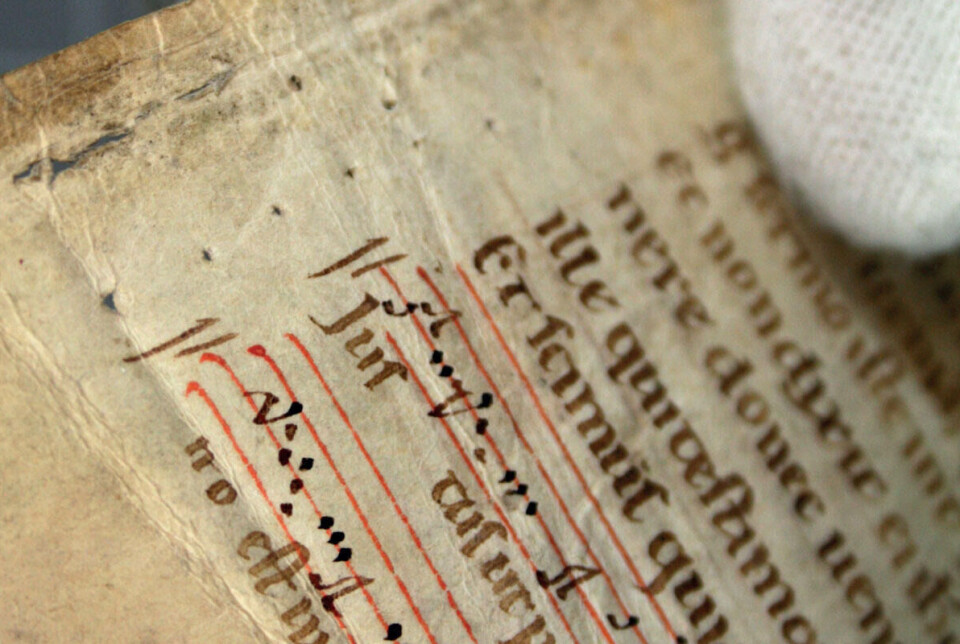

Ommundsen has studied what the fragments tell about medieval liturgy, its music, and the cult of saints.

"90 per cent of Norwegian fragments come from liturgical books, and I already had an understanding of liturgy, as I have also worked as an organist. In many fragments, the tunes are also marked as sheet music, and although I'm not a musicologist, the musical side is also interesting," she says.

One challenge to the puzzle is that pages belonging to the same book have ended up in collections in different countries.

"That's why Nordic cooperation is so essential. The research atmosphere is open and good, and it's a pleasure to work with competent people like Jaakko Tahkokallio or church history Professor Tuomas Heikkilä. For example, we have cooperated with them for 20 years already, and hopefully we will continue for another 20 years. The staff at the archives are helpful and the materials have been digitised, so materials located in different countries can easily be accessed. If this were not the case, research would be difficult," Ommundsen says.

Part of the European cultural heritage

In their time, the books were not rarities or masterpieces, but were used in ordinary parish churches on a daily basis – the priests used them to check the progress of every mass and devotional time of the year.

"What makes the collection interesting is precisely the fact that no one has selected the material to be preserved; it survived unselected and by chance," Ommundsen says.

Similar books were used all over Europe, but elsewhere than in the Nordic countries, they have not survived precisely because of their ordinariness.

"The Nordic fragment material is unique on a European scale and provides such information about the liturgy of the Middle Ages and its local and temporal variation that is not available elsewhere. At the same time, it strongly connects us to a wider European cultural heritage," she says.

There was already a commercial book market in the Middle Ages

Books copied by the same scribe have started to be recognised by the style of the initials and decorations on the books. One such cluster contains the remnants of 40 books copied by the same team in London at the beginning of the 13th century. Copying books was professional work.

"In the first year of our research project, this group of books has been studied a lot, which churches the books have ended up in and why," Jaakko Tahkokallio says. "It's been an interesting observation that the books have ended up in the emerging centres of royal power in the early 13th century. It seems that the king acted as a financier in a project done in cooperation with bishops. The acquisition was large, and the delivery of books took years, as copying one book took at least half a year."

A massive book order was made at a time when the scattered society of the Viking Age was transitioning to a centralised state power.

"The transition happened through a change in religious worldview – the God of Christianity was the ruler of the entire universe, and he delegated absolute power to the king at the local, state level."

Copying books by hand ended when Gutenberg invented the printing press, but without the developed, commercial book market of the Middle Ages and the established demand for books, the invention might not have been made.

This article was first published in Rotunda, a yearly magazine at the National Library of Finland.

More content from the University of Bergen:

-

Researchers are hoping for bad weather – so they can fly straight into the storm

-

The ice on Greenland is acting strangely. Researchers believe they finally know why

-

Early human innovation: Was climate really the cause?

-

The proteins in your blood can reveal early signs of heart problems

-

Electricity against depression: This may affect who benefits from the treatment

-

Quantum physics may hold the key to detecting cancer early