THIS CONTENT IS BROUGHT TO YOU BY the University of Bergen - read more

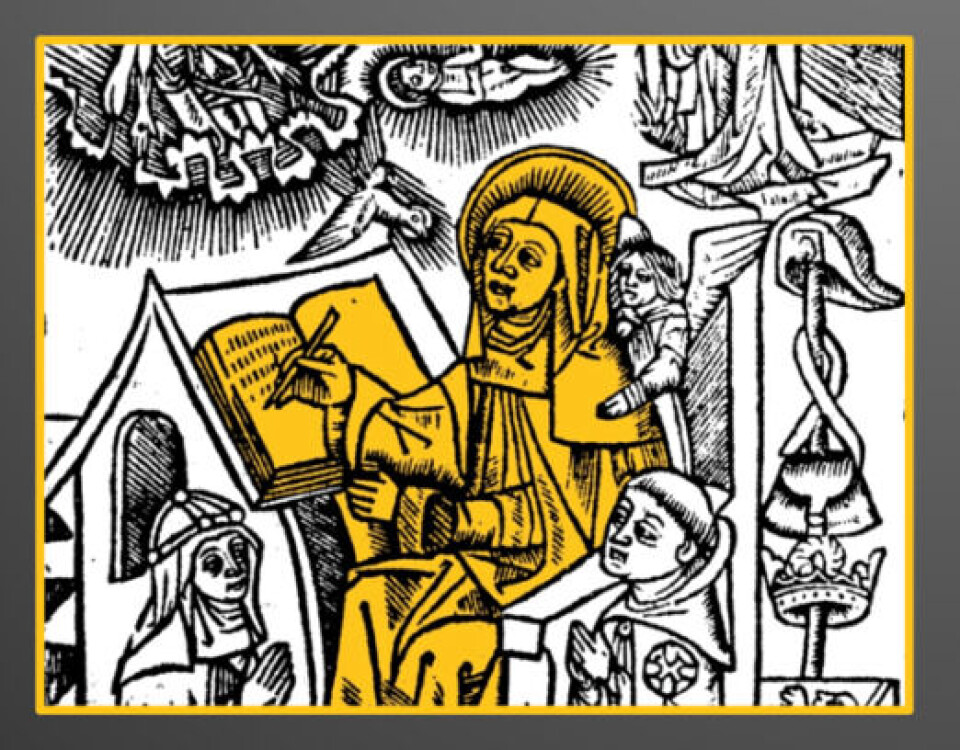

Uncovering the hidden female influence in medieval literature

Did nuns play a more active and influential role in shaping our literary canon?

“Reading has had a significant impact on my life and brings me immense joy. Studying women as active contributors to literary culture, rather than merely as passive recipients of texts, is personal for me. I relate to this group as a female reader myself,” says Laura Saetveit Miles.

She is professor at the University of Bergen's Department of Foreign Languages. Miles researches religious literature and culture from the Middle Ages, particularly in England from 1100 through the Reformation in the 1530s.

How did women readers and authors shape literature in the Middle Ages? How did religion open up new opportunities for women to create and engage with texts, even as it restricted them in other ways?

Miles has previously published a book about the Virgin Mary, presenting her as a central figure who shows that women played a role in literary culture.

England’s obsession with a famous visionary from Sweden

In her recent research project ReVISION, Miles has delved into the archives to investigate the question: How and why was St. Birgitta of Sweden (1303-73) so incredibly popular with English readers in the 150 years between 1380 and the Reformation?

"Birgitta’s popularity came from her ability to be everything to everyone: a spouse, a parent, or a widow; an aristocrat or a servant; an activist or a theologian; courageous or humble. She was relatable, yet worthy of admiration," says Miles.

The story of England’s obsession with the Swedish visionary may significantly alter the history of women writers.

Birgitta had divine visions from God, which she wrote down in Latin with the help of male confessors. The text then circulated across Europe and was translated to English once it reached England. Along the way, various male translators and scribes altered and shaped the text.

“Where does that leave Birgitta? Some might argue that she is not the author. However, if we take a narrow concept of authorship, we fail to reflect the reality of her contributions. We must consider Brigitta a writer. Restricting our definition of authorship effectively excludes all women from the history of literature,” says Miles.

"Join a convent!"

Miles plans to continue studying how women read and engaged with religious texts in places like convents, where they interacted deeply with literature despite social restrictions.

These texts often included the voices and views of women. Understanding them properly can help answer a bigger question about how women in enclosed communities were involved in literary culture.

“We often view enclosed women, or nuns, and these kinds of subjects as very strange, very foreign. But as a woman in the Middle Ages, opportunities for gaining knowledge were strictly limited. We must recognise that to become a nun was the best way to live a life dedicated to reading and literature. If you wanted an academic life like mine today, joining a convent was the way to go,” she says.

Miles will study both modern editions and lesser-known manuscripts in archives. She also plans to create new editions of notable texts that were important for women’s reading practices.

Novels combined with self-help

These texts, called devotional texts, retell the lives of the Virgin Mary and Christ. They were meant for women to read alone or in small groups to assist with prayer, contemplation, and meditation.

Nuns read them in a way similar to how we might read both a novel and a self-help book at once.

“It's difficult to hear the female voice, but we just have to know how to listen for it. The texts were written in response to women's active engagement with male authors. If we look closely for these subtle clues in the text, we can see that the women are seeking specific advice on how to navigate different needs and feelings, or on how to handle the everyday challenges of living a cloistered life. Their interactions are not merely receiving fully formed advice; it's a two-way conversation,” says Miles.

The feminist approach

Miles highlights how feminist methodologies that have emerged in recent decades help us better understand women's roles in literature.

“Feminist methodologies make our entire approach to literary studies stronger and more complex. And the fact that we are now still losing so many women's rights, shows that any feminist approach is still very important – whether the research is on medieval women or today's women,” she says.

This content is paid for and presented by the University of Bergen

This content is created by the University of Bergen's communication staff, who use this platform to communicate science and share results from research with the public. The University of Bergen is one of more than 80 owners of ScienceNorway.no. Read more here.

More content from the University of Bergen:

-

Electricity against depression: This may affect who benefits from the treatment

-

Quantum physics may hold the key to detecting cancer early

-

Researcher: Politicians fuel conflicts, but fail to quell them

-

The West influenced the Marshall Islands: "They ended up creating more inequality"

-

Banned gases reveal the age of water

-

Researchers discovered extreme hot springs under the Arctic