THIS ARTICLE/PRESS RELEASE IS PAID FOR AND PRESENTED BY NILU - Norwegian Institute for Air Research - read more

Smoke from Canada is still coming in over Norway

Updated calculations carried out by scientists at NILU show that smoke from the forest fires in Canada is still drifting in over Norway.

“As long as the forest fires are ongoing, we can expect that some of the smoke will reach Norway,” senior researcher Nikolaos Evangeliou says. “During the next few days, the smoke cloud will likely hit countries further south in Europe.”

Nikolaos Evangeliou and senior scientist Sabine Eckhardt at NILU have created an updated simulation that shows how smoke and soot particles from Canada are carried through the atmosphere. The forecast extends until 13 June.

In the simulation, the smoke emission from Canada is shown as a cloud moving over a world map. The different colours of the cloud indicate the amount of particles the cloud contains. The yellow areas of the cloud signal where there are the most soot particles in the air.

“When the smoke reaches Europe, the number of particles is much lower. This means that we can possibly see the smoke as a faint haze, and perhaps notice the smell of smoke. But the number of particles is so low that it should not cause any health hazards,” Evangeliou says.

This is how the scientists create the simulations

The forest fires in Canada are still raging, and the emission of smoke and ash into the atmosphere is very strong.

When Evangeliou, Eckhardt and their colleagues create such simulations, they first download datasets created with the help of satellite observations. These show how powerful the emission is.

Then, they model the dispersion of these emissions in the atmosphere. For this, they use meteorological data from the Global Forecast System (GFS) of the National Centers for Environmental Prediction (NCEP) in the US.

The data is fed into an atmospheric model called FLEXPART, to calculate how emissions disperse further. In addition, they use data on expected precipitation, as rain, hail, and snow can remove such particles from the atmosphere and discharge them to the ground.

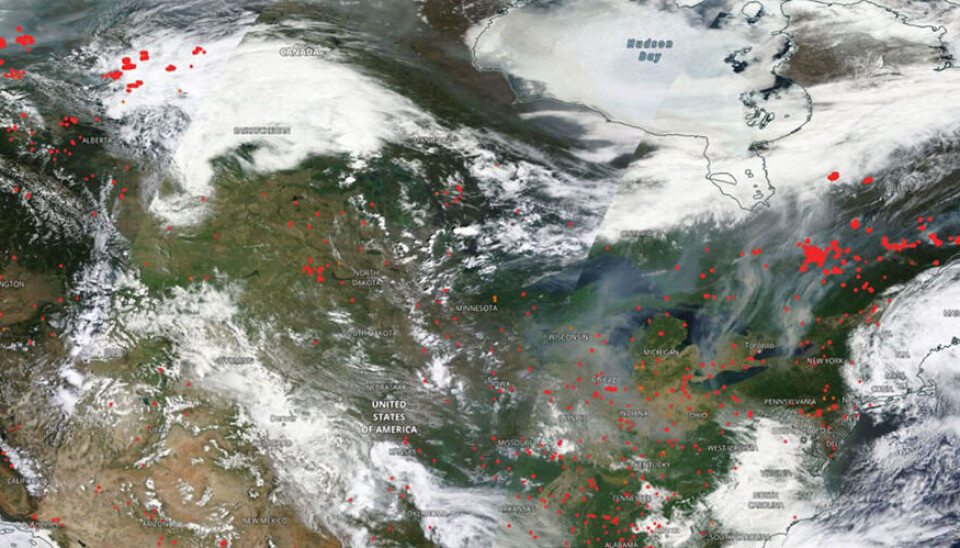

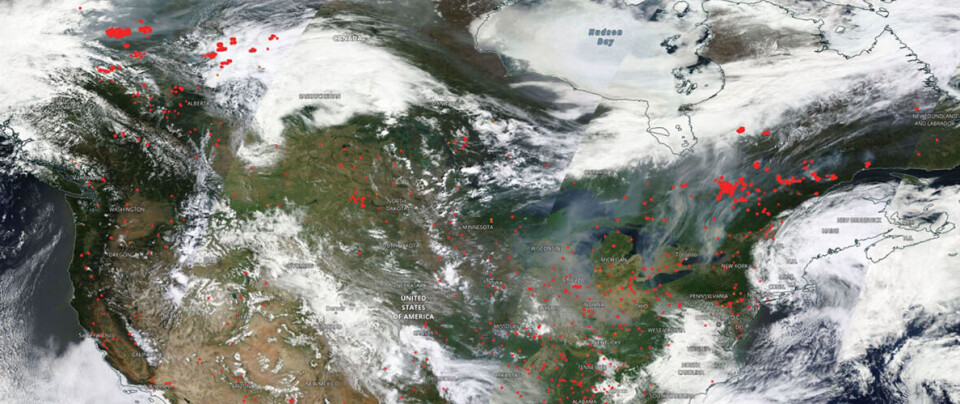

When Eckhardt wants to look at how smoke from the forest fires moves in the atmosphere, she first defines the area where the smoke is coming from. The location of active fires and their radiative power can be seen from satellite instruments. An example of satellite view from June 4 is shown in the figure below.

Eckhardt must also define how high the smoke rises in the atmosphere, a crucial detail that stems from the fire intensity. For the forest fires in Canada, the injection altitude was variable with a highest value identified at around 4 kilometres up in the air. Such a definition of width, lengthm and height for an area is called an emission box.

In FLEXPART, Eckhardt can fill the emission box with various virtual particles or gases. Some particles are heavy enough to sink quickly, while others are so light that they can be carried thousands of miles before hitting the ground.

Since we are now interested in the forest fires in Canada, they filled the emission box in FLEXPART with smoke particles. These particles are so small that as long as there is no precipitation, they can float far before sinking.

“We have actually seen cases where smoke particles from large forest fires are carried through the atmosphere all the way around the globe,” she says.

Confirms modeling with monitoring data and satellite images

On Wednesday 7 June, smoke particles from Canada were picked up by NILU’s monitoring instruments at the Birkenes Observatory in the south of Norway.

“The monitoring instruments cannot say anything about the area these particles originate from. For that, we use FLEXPART modeling, among other things,” senior engineer Are Bäcklund says. “We also have instruments that can determine the particle source. Particles have a kind of fingerprint that reveals whether they come from, for example, forest fires, industrial pollution, or sandstorms.”

On Thursday 8 June, both the FLEXPART modeling and Copernicus modeling show that the smoke cloud from Canada has moved north towards Svalbard.

The Zeppelin Observatory is on Svalbard, where NILU also has measuring instruments that can detect particle pollution in the atmosphere.

“Our instruments measure 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. When the smoke from the Canadian forest fires moves in over Svalbard, we see it the minute it hits,” Bäcklund says.

Over the next few days, the NILU scientists will follow the development of the fires in Canada closely. For this, they also use satellite data to gain a better understanding of the spatial distribution of the gases. An example is carbon monoxide (CO) and particles from the Sentinel-5P satellite.

Eckhardt and Evangeliou can also disclose that due to the large number of particles in the atmosphere, the light is refracted more than usual. This can produce extra strong colours in the sky, giving us some spectacular sunsets.

This article/press release is paid for and presented by NILU - Norwegian Institute for Air Research - read more

This content is created by NILU's communication staff, who use this platform to communicate science and share results from research with the public. NILU is one of more than 80 owners of ScienceNorway.no. Read more here.

See more content from NILU:

-

Summer in Central Europe: Drought and wildfires to be expected

-

How do you design a healthier place to live?“I would prioritise easy, car-free access to everything you need in your daily life"

-

Fires in tropical forests affect more than just the forests

-

Engineer Sam Celentano found 222 grams of gold in a laboratory. What was it doing there?

-

Air pollution levels are still too high across Europe

-

Researchers have discovered how biological particles affect the clouds over the Arctic