THIS CONTENT IS BROUGHT TO YOU BY NILU - read more

Summer in Central Europe: Drought and wildfires to be expected

In Norway, on the other hand, the risk for rain seems to be greater than the risk of forest fires.

According to Copernicus Climate Change Service, Europe has been warming twice as fast as the global average since the 1980s.

Europe is now the fastest-warming continent on Earth.

Last year was the warmest ever recorded. It is unlikely that 2025 will be any cooler.

Heatwaves are becoming more frequent and severe, with ever more widespread droughts. With such droughts, the risk of wildfires is rising globally.

Drought in Central Europe, rain in Norway

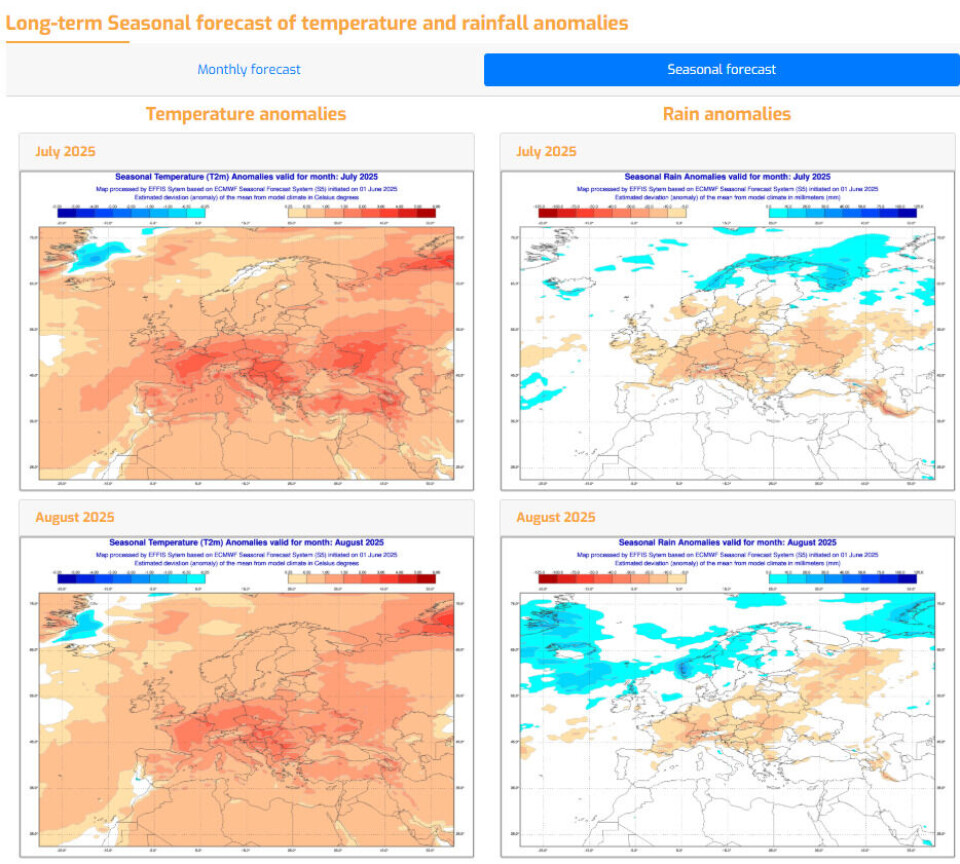

According to the EFFIS Longterm Seasonal Forecast, we can expect July and August 2025 to be hot and dry in Central Europe, says Johannes Kaiser, a researcher at NILU's Department of Atmosphere and Climate.

EFFIS is the European Forest Fire Information System.

Hot and dry weather significantly increases wildfire risk. These conditions make it easier for fires to ignite, spread rapidly, and intensify.

"Elevated temperatures and reduced rainfall dry out living and dead vegetation. When they occur at the same time, the drying of fine fuels such as grasses, leaves, and twigs on the ground is amplified. This makes them much more susceptible to fire ignition from natural or human causes,” says Kaiser.

How forecasts work

Forecasting can be explained as a process of making predictions based on the study and analysis of past and present data. When the season ends, the accuracy is measured against the actual outcome, and the model is improved accordingly.

Most of us are already familiar with weather forecasting, where weather conditions are predicted on the basis of the latest observations.

“Fire danger forecast as seen in EFFIS shows that the risk for large forest fires should be low in Norway until the end of June. While the forecast shows a warm summer, there are good chances for rain in mid-Norway in July and also in southernmost Norwegian regions in August. This is great for preventing forest fires, but not so positive if you're planning to spend the holiday here,” says Kaiser’s colleague, researcher Nikolaos Evangeliou.

The wildfires in Canada are different

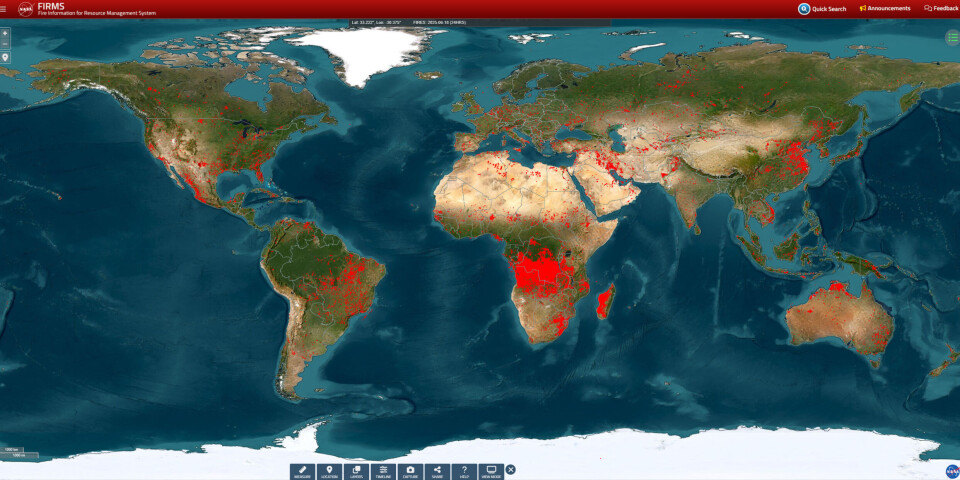

The wildfire season in Canada started in mid-May, and around 200 fires are still raging. Tens of thousands have been evacuated from their homes.

Most of these fires were ignited by human activity, according to the province of Manitoba’s Wildfire Services website.

“Wildfires are a part of the natural ecosystem, but the fires in Canada are different – and not only because of the human factor. What we see now are fires burning in areas that are normally quite wet, with large, fast-growing forests. Due to drought, these forests are now drier than usual, yielding more available fuel for the fires. In areas which normally are quite dry, you don’t accumulate so much fuel, because you have more frequent – but smaller – fires,” explains Kaiser.

In the past, it was more common for people to gather wood and dry branches from forest floors to burn for heat and cooking. By doing so, they removed fuel for wildfires. Controlled burns are one method used to prevent wildfires in vulnerable areas.

“In forests as large as in Canada, there's little to no forest management. They don’t thin out the forest, they don’t create firebreaks, there's no clearing of the forest floor. In a lot of European countries, among them my home country Greece, we do such forest management,” says Evangeliou.

More extreme wildfires

Most of Europe will never experience fires on the scale seen in Canada. There are simply no forests large enough, agree the two researchers.

“The exception is Siberia, where there have been several fires of the same magnitude during the last ten years,” says Evangeliou.

Siberia's ecosystem is similar to Canada's. It is at the same latitude and also has boreal forests – forests made up of species that can tolerate cold temperatures like spruce and fir. The name ‘boreal’ comes from Boreas, the Greek god of winter, ice, and the north wind.

During the summer of 2018, there were more than 50 wildfires in Sweden, many close to the Norwegian border. Altogether, around 216 square kilometres burned. Fire fighters from multiple countries worked together to put the fires out.

By Scandinavian standards, this was quite large. For comparison, Portugal saw more than 1,350 square kilometres burn last year. And in 2023, over 150.000 square kilometres burned in Canada – nearly half the size of Norway.

“It's a fact that the extreme wildfire risk has risen over the last 20 years,” says Evangeliou.

More content from NILU:

-

How do you design a healthier place to live?“I would prioritise easy, car-free access to everything you need in your daily life"

-

Fires in tropical forests affect more than just the forests

-

Engineer Sam Celentano found 222 grams of gold in a laboratory. What was it doing there?

-

Air pollution levels are still too high across Europe

-

Researchers have discovered how biological particles affect the clouds over the Arctic

-

Smoke from Canada is still coming in over Norway

He refers to a recent study that analysed 21 years of satellite data. It shows that extreme wildfires have more than doubled in frequency and magnitude since 2003.

Additionally, 2023 was both the hottest year on record and the year with the most severe wildfires – so far.