THIS CONTENT IS BROUGHT TO YOU BY NILU - read more

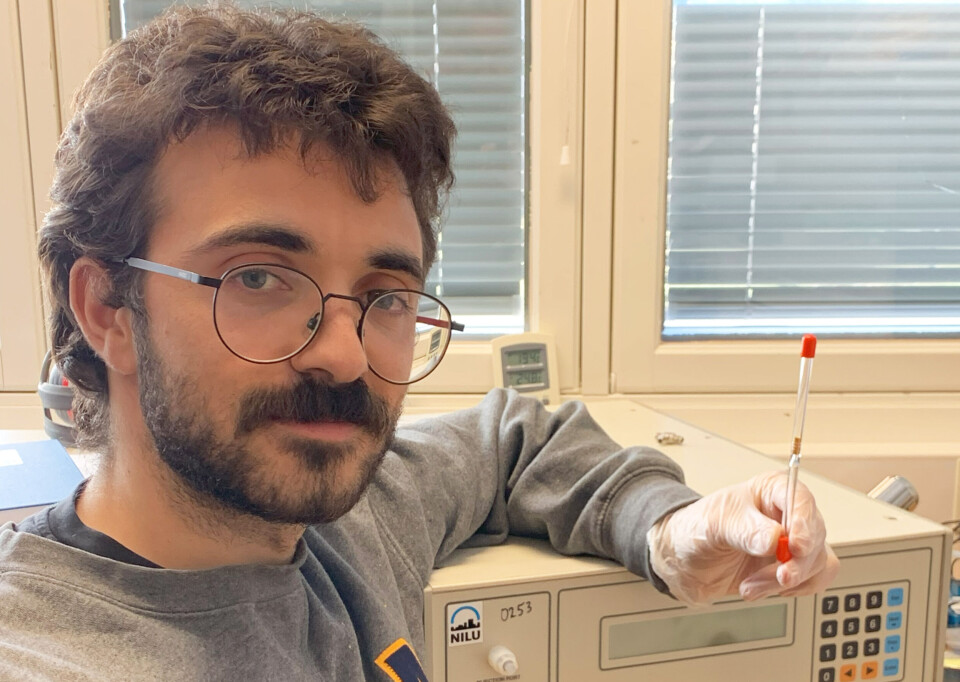

Engineer Sam Celentano found 222 grams of gold in a laboratory. What was it doing there?

The gold deposit is the remains of measurements of gaseous mercury in the air.

Earlier this year, engineer Sam Celentano took over responsibility for one of NILU’s instrument laboratories.

He started with a thorough tidying and cleaning, during which he found a bucket half full of what looked like small glass tubes filled with heavy pellets. Gold pellets.

Mercury binds to gold

“These pellets originate from our Tekran instruments, which we use to measure gaseous mercury in the air. Right now, NILU has four of these instruments running at our observatories Zeppelin on Svalbard, Trollhaugen in Antarctica, Birkenes outside Kristiansand, and Sofienbergparken in Oslo,” says Celentano.

But why is there gold in them?

“We want to measure mercury in the atmosphere, and mercury binds to gold. Ironically, the practice of using mercury to mine for gold has long been one of the biggest sources of mercury pollution,” he says.

In small-scale mining operations, they often mix liquid mercury with gold ore. The mercury binds to the gold, creating an amalgam which is then heated.

The toxic mercury evaporates into the air, leaving pure gold behind.

The process also creates a byproduct: mine tailings. These also contain mercury, and are released back into the environment, thus polluting the environment near the mines.

Trapping the mercury

The Tekran instrument works more or less as described above. Celentano explains that inside the Tekran are two small quartz tubes. Each contain a tiny capsule of gold pellets pressed together.

The instrument sucks air through the gold pellet-filled tubes, often referred to as traps. They are permeable, so air can easily move through them.

The gold adsorbs mercury from the air and traps it in the capsule. Then, the instrument heats the gold traps and flushes them with argon gas – enough for the mercury to be released into a measurement chamber, which can then give an averaged concentration.

“We don’t add any mercury to the air during this process. The amount of mercury released from the instrument is the same as was already there to begin with,” emphasises Celentano.

Costly consumables

Over time, the gold traps get clogged by dust and dirt, preventing air from passing through them. When this happens, the engineers who operate the instruments replace the used traps with new ones.

Celentano has heard that some institutions have tried to clean the traps and reuse them, but it has not been very successful. It is a time-consuming process that may be more trouble than it is worth. Other parts of the system may need more frequent servicing if the traps are constantly removed.

Additionally, he says they would also be uncertain about the quality of the measurements if they used cleaned traps instead of brand new ones.

“Over the years, my former colleagues must have replaced hundreds of such gold traps from our Tekran instruments, some of which are more than 20 years old. The traps are consumables, but since they weren’t thrown away, my colleagues obviously knew they were valuable. I don’t know if they fully realised, though, because when I found the bucket, it contained more than 150 gold traps,” says Celentano.

222.7 gram gold nugget

Celentano got help from his colleague Geir Opøien to smelt the traps in the workshop using an acetylene torch.

“Each trap weighs about 1.5 grams, so we ended up with a gold disc weighing 222.7 grams. After visiting several gold buyers in Oslo, I found one that could help both determine the karat of the gold and buy it from us,” he says.

Celentano found that few jewellers who buy gold are willing to purchase a gold lump like the one he had.

Usually, when people sell old gold, it is in the form of jewellery, which is already stamped with its karat. So he had to find a shop with an XRF instrument that could scan the gold lump and determine how pure the gold was.

“It was 24-karat gold, sitting in a bucket in our instrument lab. Amazing. We sold it for over NOK 150,000 (13,650 USD),” he says.

“You can see why people go crazy for gold”

NILU’s Monitoring and Instrumentation Technology department, where Celentano works, has many different instruments running at observatories and monitoring stations around the country.

He thinks some of them may also contain small amounts of gold or other precious metals, but not as much as the Tekran instrument.

He explains that what makes these specific instruments unique is the fact that mercury binds to gold. In other words, the gold is necessary – they do not contain previous metals just for appearances.

“It was fun to hold the gold lump in my hand, though. You can really see why people go crazy for gold. Almost a quarter of a kilo. It's probably the most massive thing I've ever picked up. Gold is almost twice as dense as lead,” he says.

All in all, the money is enough to pay for eight new gold traps – and according to Celentano, it will take around 20 years to collect as many gold traps again.

More content from NILU:

-

Summer in Central Europe: Drought and wildfires to be expected

-

How do you design a healthier place to live?“I would prioritise easy, car-free access to everything you need in your daily life"

-

Fires in tropical forests affect more than just the forests

-

Air pollution levels are still too high across Europe

-

Researchers have discovered how biological particles affect the clouds over the Arctic

-

Smoke from Canada is still coming in over Norway