THIS CONTENT IS BROUGHT TO YOU BY the University of Bergen - read more

Does the Gulf Stream exist?

Yes. But variations off the coast of Florida do not necessarily reach Norway. A new study questions the coherence of the circulation in the North Atlantic Ocean.

The Gulf Stream flows from Florida and northward off the coast of North America. Turning east, the water crosses the Atlantic as the North Atlantic Current and continues into the Norwegian Sea as the Norwegian Current.

Traditionally, this has been seen as part of a continuous loop, with water flowing northward through the Atlantic Ocean and into the Nordic Seas, where it sinks and returns southward as a deep ocean current.

Weaker transport in the Gulf Stream off Florida has been interpreted as a sign that climate change is weakening the entire circulation in the North Atlantic.

With new data, researchers question the connection between various branches of the circulation.

“You can't measure the current in a single point and expect the data to represent the circulation of the entire North Atlantic,” says Helene Asbjørnsen.

She is an oceanographer at the University of Bergen's Geophysical Institute and the Bjerknes Centre for Climate Research.

Together with colleagues from Bergen, Oxford, and Southampton, Asbjørnsen has compared current data from different regions of the North Atlantic Ocean over the past decades.

In a recently published study, researchers show that the connection between variations in the real Gulf Stream off Florida and the water that reaches Norway and the Nordic Seas is small on time scales of years or decades.

While the current off North America weakened in the decade following 2005, the inflow to the Norwegian Sea increased.

An ocean of gyres

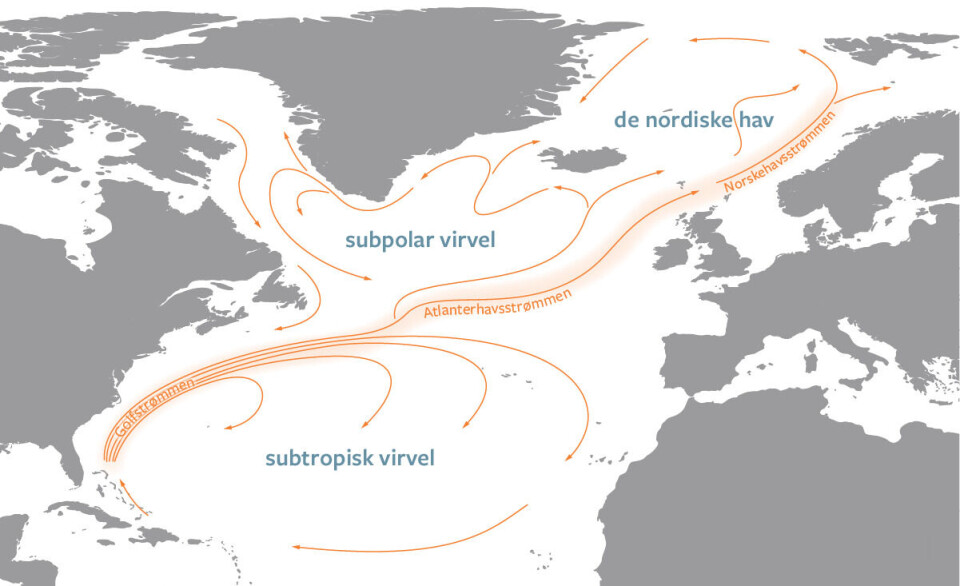

The surface currents in the North Atlantic consists of three large gyres.

Far south, in the subtropical gyre, the water follows the Gulf Stream northward in a narrow, concentrated band. To the north of this lies the subpolar gyre. The last gyre is located within the Nordic Seas and includes the Norwegian Current, which follows the Norwegian coast northward towards the Barents Sea and Svalbard.

Water flows to the north, but also veers off to circulate within the gyres. Whether changes in the south propagate to Europe and Norway depends on the amount of water that continues on to to the next gyre.

Limited long-distance connections

In the new study, researchers have compared current measurements from various locations in the three gyres over the past decades.

From the ocean outside Stad in Western Norway, current strength has been registered regularly since 1995. Data for the Gulf Stream off Florida goes back to 1982.

Comparisons show that variations in the current strength in each gyre rarely propagate to the next. The reductions registered in the Gulf Stream off North America are not seen in the middle of the Atlantic or in the Norwegian Sea.

“The atmosphere is important,” says Asbjørnsen.

The high pressure at the Azores and the low pressure systems further north vary in strength and location. The pressure controls the wind, and changes in high and low pressure can explain how a gyre strengthens without more water being transported to the next gyre.

The Gulf Stream exists

The ocean currents in the North Atlantic are not completely disconnected from each other.

In a previous study, Helene Asbjørnsen found that two-thirds of the water off the Norwegian coast came from the Gulf Stream off Florida.

Climate models are used to simulate ocean currents through longer time periods than the observational record. Over many decades, such simulations suggest that the North Atlantic behaves more like a coherent system.

Helene Asbjørnsen emphasises that the new results concern variations in ocean currents on time scales covered by available measurements.

“Seeing signs of long-term changes in the observations is difficult with data series that are short and dominated by large regional variations from year to year and decade to decade,” she says.

Climate models also consistently show that climate change will weaken the sinking in the north, which, together with the wind, drives the Atlantic ocean currents.

The wind drives the water northward in surface currents. In the north, the water becomes cool and dense, sinkning and returning southward at depth. Both the wind and the sinking contribute to driving the North Alantic Ocean circulation. (Animation: Eli Muriaas / Bjerknes Centre)

References:

Asbjørnsen et al. Observed change and the extent of coherence in the Gulf Stream system, Ocean Science, vol. 20, 2024. DOI: 10.5194/os-20-799-2024

Asbjørnsen et al. Variable Nordic Seas Inflow Linked to Shifts in North Atlantic Circulation, American Meteorological Society, 2021.

This content is paid for and presented by the University of Bergen

This content is created by the University of Bergen's communication staff, who use this platform to communicate science and share results from research with the public. The University of Bergen is one of more than 80 owners of ScienceNorway.no. Read more here.

More content from the University of Bergen:

-

The ice on Greenland is acting strangely. Researchers believe they finally know why

-

Early human innovation: Was climate really the cause?

-

The proteins in your blood can reveal early signs of heart problems

-

Electricity against depression: This may affect who benefits from the treatment

-

Quantum physics may hold the key to detecting cancer early

-

Researcher: Politicians fuel conflicts, but fail to quell them