THIS CONTENT IS BROUGHT TO YOU BY the University of Bergen - read more

Breakthrough in forecasting El Niño phenomenon in the Atlantic

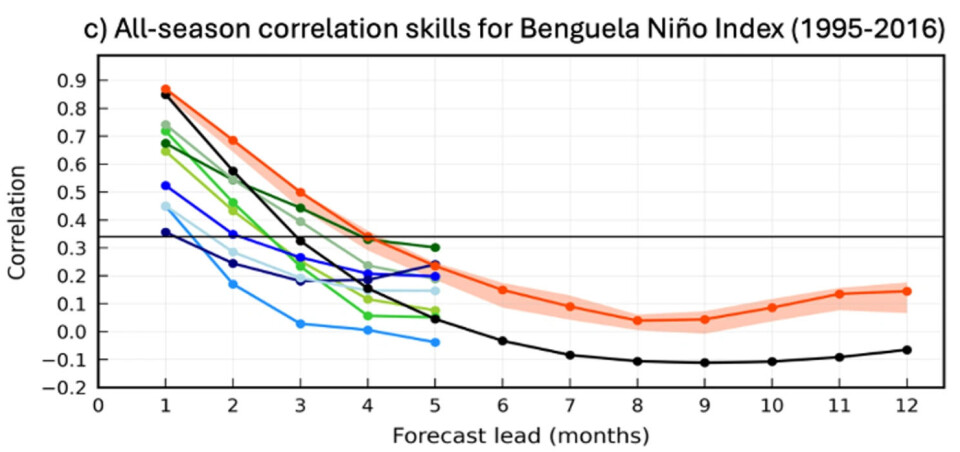

For the first time, researchers can use artificial intelligence to predict South Atlantic ocean warming linked to the El Niño phenomenon up to four months in advance.

El Niño is when unusually warm surface waters appear in the central and eastern Pacific Ocean near the equator. There is also a smaller but similar phenomenon in the tropical Atlantic Ocean.

The El Niño phenomenon in the South Atlantic and the Benguela Current – which flows along the west coast of southern Africa – has a significant impact on the tropical Atlantic region, leading to extensive effects on local marine ecosystems, African climates, and the El Niño Southern Oscillation.

No one has been able to predict warm events in this region until now.

“We're extremely excited because it was the first time we could actually produce some predictions useful for communities building traditional models and achieving that goal that we had two years before,” says Marie-Lou Bachèlery.

The study was recently published in Science Advances.

A huge influence

The Tropical Atlantic Ocean lies between the Brazilian coast to the west and the West African coast to the east.

The Central Atlantic Niño is characterised by warm sea surface temperatures in the central equatorial Atlantic, while the Eastern Atlantic Niño features warming closer to the West African coast, in the eastern equatorial Atlantic.

As a key part of the global climate system, changes in the ocean affect local weather patterns, marine ecosystems, and the livelihoods of people who depend on the ocean's fish resources.

The South Atlantic is one of the regions showing quite strong ocean warming. This is problematic for a lot of things, especially fisheries. That’s why predicting extreme events like Atlantic and Benguela Niño events is crucial.

“My idea was to do predictions of those events using climate models. The project got funded through the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions and after a year and a half of work, we realised that it didn't work and that we were kind of in a deadlock situation,” says Bachèlery.

A new approach

At the time, Bachèlery was working at the University of Bergen's Geophysical Institute. She is now working at the Euro-Mediterranean Center on Climate Change in Italy.

Climate models often struggle to predict warm events in the tropical Atlantic due to their low resolution.

These models fail to accurately simulate upwelling – where wind-driven processes bring deeper, cooler water to the surface. Properly capturing these fine-scale processes requires high-resolution modeling.

Today's models therefore show significant temperature biases in the region. This, in turn, leads to more errors and inaccurate predictions.

Bachèlery saw possibilities in machine learning and artificial intelligence.

“I know the region very well. I knew exactly what I needed to put in to predict those events,” she explains.

Now it's possible to predict the events

Professor Noel Keenlyside was Bachèlery’s supervisor and has worked with prediction for many years.

“For the first time, it's actually possible to predict these events and overcome the issue of model errors by using a different approach. Many people have been trying to predict that area for a few decades, that's why Bachèlery’s results are exciting,” he says.

Being able to predict warm events will be very useful for fisheries.

“When extreme events occur, managers may limit the fishing in this region to reduce effects of the additional pressure from the environment,” explains Keenlyside.

When they first got the results, Bachèlery could not believe what she saw.

“I rechecked what felt like a billion times to make sure that we were not over-predicting, because that's a common feature in machine learning," she says.

Accurate predictions

To make predictions, the researchers fed the machine temperature maps from the region they were interested in. The model then identified patterns and regions that helped it make accurate predictions for the next two months, based on real data.

“The machinery wasn't doing random stuff. It was actually relying on real physical mechanisms that exist. That's the most interesting part for me,” says Bachèlery.

She explains that even though the system was developed for this region, the whole technique can be used for any system. Bachèlery, Keenlyside, and other researchers are now working to make these forecasts even more accessible.

“We're in dialogue with forecast users from the National Institute for Fisheries in Angola to further improve and refine the information to their needs. It's particularly pleasing to see that basic research is becoming societally relevant,” says Keenlyside.

Reference:

Bachèlery et al. Predicting Atlantic and Benguela Niño events with deep learning, Science Advances, vol. 11, 2025. DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.ads518

This content is paid for and presented by the University of Bergen

This content is created by the University of Bergen's communication staff, who use this platform to communicate science and share results from research with the public. The University of Bergen is one of more than 80 owners of ScienceNorway.no. Read more here.

More content from the University of Bergen:

-

Electricity against depression: This may affect who benefits from the treatment

-

Quantum physics may hold the key to detecting cancer early

-

Researcher: Politicians fuel conflicts, but fail to quell them

-

The West influenced the Marshall Islands: "They ended up creating more inequality"

-

Banned gases reveal the age of water

-

Researchers discovered extreme hot springs under the Arctic