THIS CONTENT IS BROUGHT TO YOU BY the University of Bergen - read more

These researchers are hoping for bad weather. The goal is to see whether ice-free waters off Greenland can counteract changes in the Atlantic

A winter expedition aims to shed light on unexpected consequences of climate change.

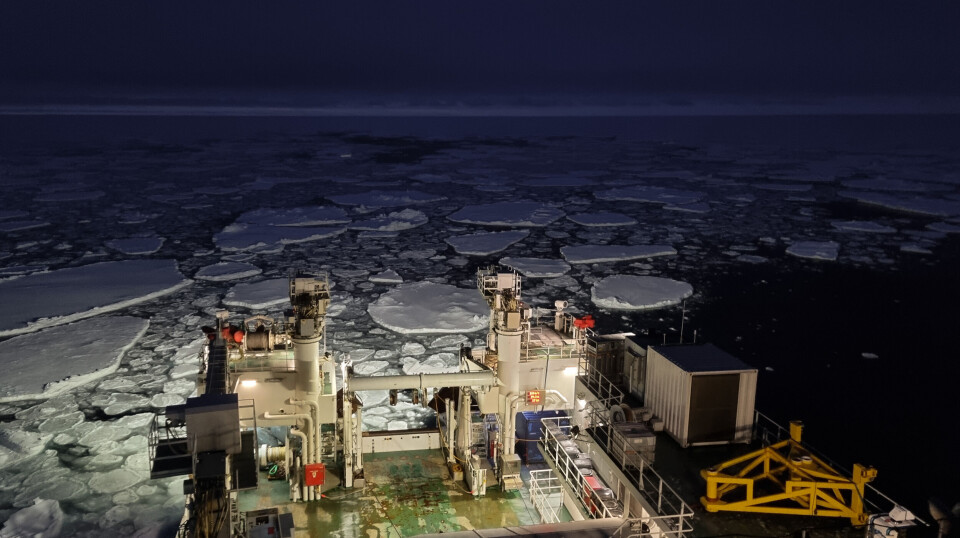

The beams from two spotlights hit the waves a few metres ahead of the bow. Everywhere else it is dark.

It is early February, and the icebreaker Kronprins Haakon is heading westward in the Fram Strait.

Along with the crew on board, there are about 20 researchers. They are hoping for bad weather.

“We are here in winter for a reason,” says expedition leader Kjetil Våge. He is a professor at the University of Bergen's Bjerknes Centre for Climate Research and the Geophysical Institute.

Climate change draws the ice edge closer to the coast of East Greenland, leaving large ocean areas open.

Våge and his team of researchers want to find out whether this may compensate for another effect of climate change, namely the weakening of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC). This is a system of ocean currents that moves warm water north and cold water south.

In the coming weeks, the researchers will conduct measurements in the Greenland Sea and Iceland Sea. This is a region rarely visited at this time of the year.

Climate change can, in theory, weaken currents

The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation works a like a loop where warm water flows northward near the surface, sinks, and returns southward at depth.

The sinking of the water occurs because it cools when exposed to cold polar air.

Cold water is heavier than warm water, and the cold water mixes downward and becomes deep water.

In climate model simulations of the future, this loop weakens – both the deep-water current flowing southward and the Gulf Stream on the surface.

The main cause is an increase in precipitation and meltwater from glaciers and the Greenland ice sheet, which form a light and stable surface layer in northern regions.

The warm Atlantic water from the south flows beneath this layer, no longer exposed to the air above. As a result, the water loses less heat to the atmosphere and does not become as dense as it used to.

This means that less water sinks, and the deep water current heading south weakens.

This is the theory, supported by climate models. So far, however, no such weakening has been observed.

Could something have been overlooked?

Open waters change the game

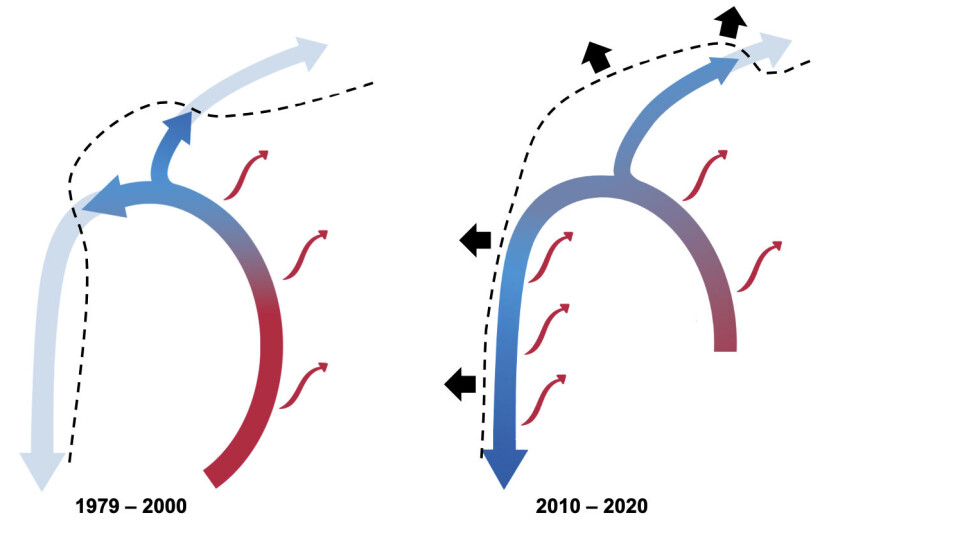

Kjetil Våge's hypothesis is that loss of sea ice to the east of Greenland may counteract the effects of less sinking water elsewhere.

Right there, over Greenland's continental slope, leads and open waters may have more substantial consequences than in most other regions.

To understand why, we must follow the current from the Atlantic Ocean.

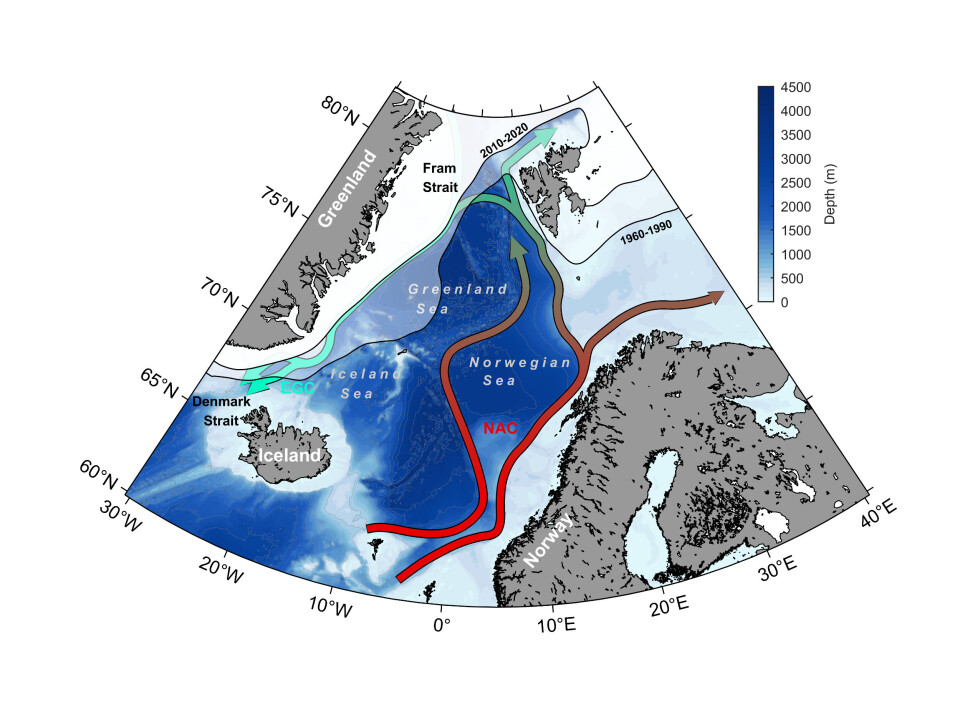

Most of the warm water from the Gulf Stream enters the Nordic Seas on the eastern side, between Iceland and Scotland.

The current continues northward along the coast of Norway and Spitsbergen before turning westward into the Fram Strait, between Svalbard and Greenland.

Merging with water that has made a circuit through the Arctic Ocean, this water continues southward along the coast of Greenland as the East Greenland Current.

Less cooling in the east, more in the west

The water has been cooled all along the route through the Nordic Seas, but so far, most of the cooling has taken place in the Norwegian Sea before the water reaches the Fram Strait.

The East Greenland Current has flowed under a protective lid of sea ice, just inside the ice edge off Greenland.

As the ice edge withdraws closer to the coast, long stretches of the East Greenland Current become exposed at once.

Thus, climate change, which causes less transformation of water in the Norwegian Sea, could open large areas at the continental slope of Greenland to deep-water formation.

The East Greenland Current leads directly into the Denmark Strait, where water cascades down the slope to the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean.

If the ocean off Greenland turns out to produce more deep water than before, it could compensate for reductions in other regions.

The overturning circulation in the Atlantic may be more stable than previously thought.

Most important in winter

Until now, researchers have lacked data for evaluating whether this hypothesis is correct.

Water cools the most in winter, and deep water forms exclusively during the cold season.

Winter expeditions in the Greenland Sea and Iceland Sea are rare. In much of the region where Kronprins Haakon is heading, measurements have only been taken in summer.

“These regions used to be inaccessible,” says Kjetil Våge.

To obtain data from the seas off East Greenland, you must either have an icebreaker or stay outside the ice edge

“Now, waters that were previously covered with ice are open, and we have an icebreaker. We can go all the way onto the shelf and get the measurements we need,” he says.

Hoping for strong winds

The stronger the wind and the colder the air, the more the surface water cools and the more deep water is formed.

The strongest cooling occurs when cold, dry polar air crosses the ice edge and blows over open waters. Such outbreaks of cold air are exactly the kind of bad weather the researchers hope to experience in the Greenland Sea and Iceland Sea.

To the south, a low-pressure system is developing. The weather forecast looks promising for researchers wishing for rough seas.

They have five weeks of winter before they have to return the icebreaker.

This content is paid for and presented by the University of Bergen

This content is created by the University of Bergen's communication staff, who use this platform to communicate science and share results from research with the public. The University of Bergen is one of more than 80 owners of ScienceNorway.no. Read more here.

More content from the University of Bergen:

-

Electricity against depression: This may affect who benefits from the treatment

-

Quantum physics may hold the key to detecting cancer early

-

Researcher: Politicians fuel conflicts, but fail to quell them

-

The West influenced the Marshall Islands: "They ended up creating more inequality"

-

Banned gases reveal the age of water

-

Researchers discovered extreme hot springs under the Arctic