THIS CONTENT IS BROUGHT TO YOU BY University of Oslo - read more

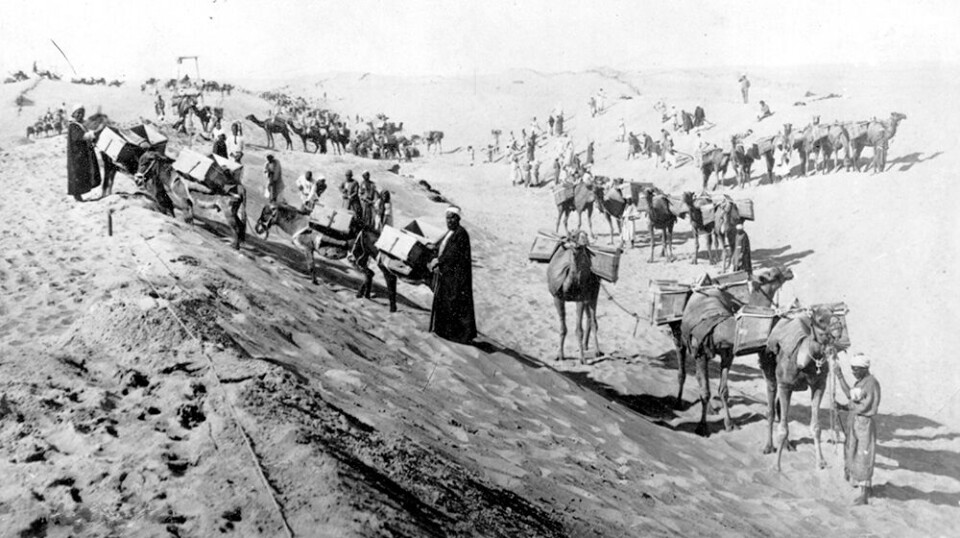

During the construction of the Suez Canal, people from Europe travelled to Egypt in search of work

Historian Lucia Carminati believes that their stories are an important corrective to how we think about immigrants today.

The 193-kilometre-long Suez Canal connects the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea. When it was completed in 1869, it reduced the travel time between Europe and Asia by 30 days, according to the Great Norwegian Encyclopedia (link in Norwegian).

Much has been written about the Suez Canal Company and the men who led its construction, about the ruler of Egypt at this time, and the economic and political aspects of the history of the Suez Canal.

However, we know little about the people who built the waterway from Port Said to Suez. Historian Lucia Carminati wants to remedy this imbalance.

“I believe that ordinary people are the real material of history,” she says. Carminati is associate professor at the Department of Archaeology, Conservation and History at the University of Oslo.

In her book Seeking Bread and Fortune in Port Said: Labor Migration and the Making of the Suez Canal, 1859–1906, she focuses on the migrants who, for various reasons, sought their fortune on the spit of land that connects Africa to Asia.

Those who, from different parts of the world, reached the newly established town of Port Said, in the southeast corner of the Mediterranean.

“For me, the Suez Canal represents the many major infrastructure projects that were carried out in the 1800s. Such projects affected the workforce, they led to migration and suffering, even the death of many people – men, women, and children,” Carminati says.

It is the fate of these people she wants to shed light on.

The one who seeks will find

To find these stories, Carminati has assembled fragments from archives around the world. She has included seemingly trivial or banal details to give life to the countless individuals we often don’t know much about.

“Although governments often tone down these voices, we can find traces of them in state or diplomatic archives. We find them if we're just curious and persevering enough. For example, in letters from relatives of the migrants, those who did not leave, that wonder what has happened to their loved ones, whether they are dead or alive,” Carminati says.

“We don't always know the answers to their questions, but we do know that the relatives were looking for them. That means we have information about the migrants, who they were and when they left,” she says.

Hierarchies based on racial identity, ethnicity, and gender

Where did they come from and who were they, those who sought work in Port Said and along the canal in Egypt?

“They came from different places, not just from the area along the Mediterranean. People came from the southern parts of Europe and Central Europe. They came from other parts of the Ottoman Empire, especially Syria, but also from areas in North Africa. In addition, people came from the south, from Sudan and Nubia,” Carminati says.

Some came voluntarily to the canal building project. Others, especially Egyptians, were forced and lived almost as slaves. This created hierarchies in the workplace.

“The position of individuals in this hierarchy was based on alleged racial identity, ethnicity, nationality, and of course on gender,” Carminati says.

When so many arrive in a new area, a parallel economy emerges around the workplace.

“This is not just a story about masculinity and physical labor. It is also a story about the service industry, cafes, inns, brothels, and laundries – services that are needed when many people gather in one place,” Carminati says.

Port Said

This was most evident in Port Said, the city that emerged out of nothing during the construction of the Suez Canal.

When the first 150 workers arrived in 1859, they lived in tents around a wooden shed. Ten years later, there were 10,000 permanent residents there.

“Everyone who settled in Port Said was a newcomer. On the one hand, there was a cosmopolitan ideal where anyone could blend in and find their place. On the other hand, we see that inequalities and social hierarchy were very present in Port Said,” Carminati says. “From the get-go, Arabs were expected to live in what was defined as the Arab village. Europeans were supposed to live in the European Quarter.”

The use of the words ‘village’ and ‘quarter’, says something about how the different groups were viewed.

“At the same time, we see how people constantly cross these borders. We see the realities of life in a diverse city. We see that people mix, but they are not equal members of an ideal cosmopolitan society,” Carminati says.

What laws should be followed?

Keeping order in such a situation was not easy, and sometimes it bordered on lawlessness.

Nor was it always obvious which laws one should follow. The authorities in Cairo tried to gain control of the territory. At the same time, Europeans had a special position in the Ottoman Empire where they were subject to the jurisdiction of their homeland and their local representatives.

“In addition, the French Suez Canal company acted as a state within the state. They tried to control the migrants and wanted the workers to be focused and productive, not wasting their time drinking or visiting brothels,” Carminati says.

“This created room for transgressions. We see how people challenged the laws to make a living in ways that were defined as illegal by the government. For example, smuggling.”

The opposite direction of today's migration

Carminati finds it difficult to compare the migrations of the 1800s with what we are witnessing across the Mediterranean today. The world is completely different.

Nevertheless, she believes it is important to be aware of how migration has taken place throughout history.

“In my book, I show how people crossed the Mediterranean in the opposite direction just over a century ago. Europeans looked for opportunities in the Middle East, especially in Egypt, and local authorities worried that these “swarms” of unruly immigrants would create disorder and chaos and challenge law and order,” Carminati says.

“It is an important corrective to how we think about immigrants today. People in the West were yesterday's migrants.”

Reference:

Carminati, L. 'Seeking Bread and Fortune in Port Said: Labor Migration and the Making of the Suez Canal, 1859–1906', University of California Press, 2023. (Summary)

The official book launch will take place at Scene HumSam on Blindern on December 8th.

This content is paid for and presented by the University of Oslo

This content is created by the University of Oslo's communication staff, who use this platform to communicate science and share results from research with the public. The University of Oslo is one of more than 80 owners of ScienceNorway.no. Read more here.

More content from the University of Oslo:

-

Mainland Europe’s largest glacier may be halved by 2100

-

AI makes fake news more credible

-

What do our brains learn from surprises?

-

"A photograph is not automatically either true or false. It's a rhetorical device"

-

Queer opera singers: “I was too feminine, too ‘gay.’ I heard that on opera stages in both Asia and Europe”

-

Putin’s dream of the perfect family