THIS ARTICLE/PRESS RELEASE IS PAID FOR AND PRESENTED BY NTNU Norwegian University of Science and Technology - read more

Nine hundred people from one Norwegian county donated their bodies to research when they die. Why?

Why do they do it, and what are the bodies actually used for? Welcome to the anatomical laboratory at NTNU.

The sight of twelve blue, plastic-covered bodies lying all in a row on their respective tables is almost beautiful. A plastic skeleton stands as a kind of guide next to each table.

It is difficult to imagine that these bodies have ever been alive. They are wrapped in damp cloth and plastic to prevent dehydration. These bodies are used in the anatomy course for medical students, but this room is still quiet for the moment. It's a quiet filled with respect.

Bodies needed for teaching

“We regularly receive body donation agreements,” says senior engineer Jørn Ove Sæternes at NTNU. He has worked in this field since the anatomical laboratory – part of NTNU’s Department of Clinical and Molecular Medicine – was established in 1993.

“Since then, more than 900 people have signed on to be donors. We need about 25 pre-prepared bodies a year to meet our needs,” says Sæternes.

The agreement states that the body shall be handed over to the Department of Clinical and Molecular Medicine after death and can be used for teaching and medical research if the department needs it.

“The need is there, and it’s increasing. We need donated bodies for educating students, health professionals and doctors. They’re also used for research and for training in new and complicated surgical methods, for example.”

Previously, only medical students and doctors used prepared cadavers for teaching anatomy and surgical techniques. Now both radiography and physiotherapy students have classes where they examine muscles, tendons and nerves.

The course is very useful, according to the students who have taken it.

But is it really necessary to use body parts of deceased people for student courses today? Can't we see and learn just as well with digital tools?

Not the real thing

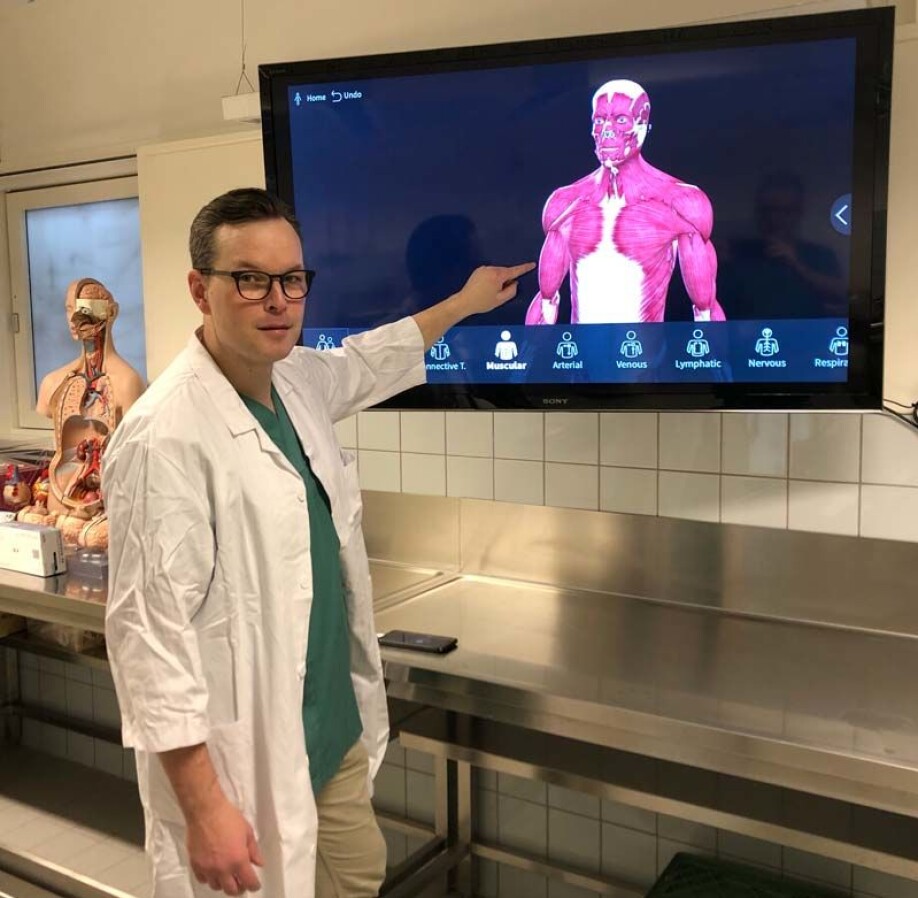

“We have great digital programs that show the body layer by layer, where you can take away and overlay whatever you want.”

NTNU Associate Professor Michel van Schaardenburgh demonstrates on the big screen. The body can be moved and enlarged from all sides just by moving one’s fingers on the screen. With a few swipes, he removes both skin and muscles.

“But it isn’t the real thing,” he says.

"The real thing" lies on the four tables behind him.

Four students stand around each table. They have a serious but tense look on their faces. They know that under the sheets are human body parts – preparations – laid out to enable the students to see how the human body is created – for real.

The sheets are removed and reveal leathery yellow body parts. On one table the feet are cut at the ankle, and the skin is partially removed to reveal muscles, tendons and nerves. On the other tables are other parts of the leg, in medical language called the lower extremities.

The physiotherapy students have donned blue plastic gloves and are ready. Seriousness has become curiosity. Carefully they lift the specimens and begin exploring.

Questions and comments fly. “What’s this? How are these connected?” “Oh, this must be a nerve. Check this out – I didn’t think the sciatic nerve was so thick.”

“This must be a woman's foot,” says another student and compares sizes.

Van Schaardenburgh stands in the background and observes the activity. The students are supposed to figure out as much as possible themselves, using drawings to assist them. But they quickly find out that not everything looks the way it appears in the drawing.

“You can see,” he says, “how the drawings show the idealized body as a template. But every individual here on Earth has their own body, which is different from everyone else's.”

A childhood song sneaks into my head: "A lot is different, but inside we’re the same" – or maybe not, after all.

Seriousness has become curiosity. Students carefully lift the specimens and begin exploring.

Biology is variation

“The idea that we’re the same inside is just nonsense.” Professor Jostein Halgunset almost snorts as he sits at the desk surrounded by papers and books from floor to ceiling.

“By definition, biology is variation. We’re part of nature and one variant of the many millions of species that exist on Earth. We humans have also adapted and succeeded extremely well this way – at least until now.”

Halgunset helped establish NTNU’s anatomical laboratory in 1993, which enabled the university to offer the entire medical school programme in Trondheim.

“The students were supposed to take anatomy, but we had no bodies, preparations or facilities. We got into action and with the help of good colleagues, established a course for the medical students,” he says.

Thousand-year-old tradition

The daily activity in anatomical laboratories is an ancient tradition around the world. This method of acquiring knowledge about the human body has been used for at least two thousand years.

Leonardo da Vinci was known for studying the human body so that he could draw bodily forms more accurately. In ancient Alexandria, the intellectual capital of the day, the practice was also common.

In Europe, performing dissections went out of fashion in the Middle Ages and was periodically banned by the church, but in the 15th century the large universities resumed the tradition. Dissections were made in "anatomical theatres" as entertainment and as a way to create an interested audience, Halgunset says.

In Norway, the dissection of human corpses was performed for the first time around 1750. A doctor in Bergen and one in Oslo were then granted royal permission to "anatomize dead slaves" for the training of surgeons and midwives. (Source: Store norske leksikon)

And some cultures knew more than others – such as the Scandinavian cultural circle – about how the body is put together.

“Texts from the 13th century indicate that the Persians already knew that the heart is a central point and that the blood circulates in the body, whereas at that time we believed that the blood was produced continuously in the liver and flowed out of the body through veins,” says Halgunset.

Gray’s anatomy

In addition to discovering that people are quite different from each other on the inside, surgeons use the preparations to practice surgical techniques. They can never do that in the same way with digital tools.

“Some people think that an app or a book is just as useful, but that just isn’t so. Not even this book,” Halgunset says.

He jumps up from his chair and picks up the medical "bible": Henry Gray's Anatomy of the Human Body. It is a beast of a book that gives a full overview of the body, purely anatomically. And for TV viewers with a penchant for medical series, indeed the book has lent its title for the "Grey's Anatomy" TV series.

But books and bodies are two different things. A human body is a 3D model. You can observe and feel the different structures, get an understanding of what they look like and how they’re connected to each other. Muscles and bones and other organs differ from individual to individual. These distinction do not appear in the usual books that show a schematic picture of the average person.

The first meeting

During their first year of study, medical students take a course in dissection, where they focus on human anatomy. Groups of students are each given their own body for this purpose.

For some students, the first meeting is exciting, and they even almost look forward to it, while others experience a lot of stress and anxiety associated with this course. Most people feel a mixture of excitement and fear.

Excited and a bit scared is how medical students Cathrin Mehl and Kristine Høgli described their first encounter with a dead body, too.

What they remember most is the smell.

“It’s unusual, a kind of chemical, somewhat foul smell.” They inhale through their noses and look out across the hall.

It's been a few months since they were last here. In front of them lies a plastic-wrapped body. They slowly begin to unpack it.

This time they feel more prepared, unlike their first time in the spring of 2019 when they had a lecture and watched a short preparatory film before they were ushered straight into the dissection hall.

Mehl has a gentle face and probably smiles often. Right now, though, she's serious, although she wasn’t really dreading this encounter.

“We talked about it ahead of time and had a lecture. But the smell in the dissection room is unusual,” she says.

“I was excited about what it would be like. It can be a little violent,” says Høgli and laughs a little.

“Luckily, what we imagined beforehand was worse than it turned out to be, and everything went really well,” she says.

The way the instruction happens is that the students distribute the six to seven body parts on each side of the body and then have half a preparation as theirs to work with. They start exploring the back first, the least personal part of the body.

“I remember that our preparation had such incredibly elaborate nails, she must have had them done somewhere. Then it suddenly became very personal for a while,” says Mehl.

Once nerves and emotions are brought under control, it’s time to get started.

“We have a large manual that Professor Halgunset was involved in creating. Then we unpack the body and follow the description. It’s a bit frustrating in the beginning, because we have no idea what we’re looking for,” says Cathrin.

Sometimes they might be making cuts, finding different muscles, nerves, and blood vessels. The face is always covered. They investigate the head, brain, pelvis and hands in a later course.

Both students agree that this is a unique way to learn and that overall, it’s fascinating to be able to touch the heart, lungs and internal organs and see how everything is connected.

“Both of us are happy and grateful that we have the opportunity to look at the human body the way it actually is,” says Mehl.

Sharing your wishes

What happens when the person who signed a donation agreement dies? Who is responsible for preparing the body so that it can be used in research and teaching contexts? The journey from a human being of flesh and blood to a preparation that students examine is a long one.

“When you sign the agreement to donate your body to science, you can check whether you give consent for the department to use parts of the body to produce teaching materials for the department, in addition to their normal use in teaching and research.

These parts typically include the arms and legs, including the hands and feet. The rest of the body is cremated and buried according to the family's wishes.

These preparations, most often parts of the upper and lower extremities, are used for teaching physiotherapy students, for example.

Sæternes has worked in the field of body preservation for a long time. Norway offers no special training programme for preparing cadavers, but people in the field learn the methods from each other. When a donor dies, the body must be transported to St. Olav's hospital as quickly as possible, and no later than 48 hours after death.

“This is to ensure the best possible starting point for making good preparations. The decomposition processes set in immediately after death. What happens next with the body depends on what the donor has agreed to,” says Sæternes.

For Sæternes and colleague Gunnar Hansen, this means that they have to wear protective equipment, respiratory protection and full-covering safety glasses when they perform embalming. Then fixative fluid is injected into the body. They use numerous, sometimes dangerous, chemicals in this work, so protection is important.

“Believe it or not, this is something you sort of get used to, but you should always be humble in handling the dead,” says Hansen. He started working in an anatomical laboratory by chance after being a porter at the hospital for a number of years.

Why donate your body?

Now we return to the physiotherapy students for a while. The preparations that the students are examining are very old. Some may date as far back as the 1990s. These specimens are wet preparations that are immersed in liquid between each use.

The preserved bodies last a long time, but they become worn from repeated use. Producing permanent preparations requires a lot of work and takes a long time. Anyone who donates their body can agree to Sæternes and his colleagues making permanent preparations that can be used for several years.

We thus come full circle back to the individuals who are the starting point for this article –the donors.

What do people who at some point during their life decide to donate their bodies to teaching and research think about? Why do they do it, and who are they?

Sæternes manages the donor archives. Since its inception, more than 900 people have given their consent for their bodies to be used for research and teaching when they die.

“Donors can be young, old, healthy or sick,” says Sæternes. You can enter into a donation agreement once you’ve reached the age of 18. But most people are significantly older, and many are already ill when they sign their agreement.

Easy choice to make

For Brit Renanger (79) from Hommelvik in Malvik municipality, it was actually her father-in-law who got her thinking about being a donor.

“When he died in 2003 at 101 years old, he had signed an agreement to donate his body for research,” she says.

After his death, she and her husband began to think about whether they should do the same. Both are the active pensioners in the municipality's cultural scene. Brit Renanger was a nurse and head nurse in her working life.

“I know how important it is for universities to have enough material to conduct teaching and research,” she says. “So it wasn’t any problem for me to make this choice. I participated in dissection during my nursing studies.”

Their relatives are well informed about the choice they’ve made, and no one has objected.

“But since it currently takes up to two years before the remains are returned in the form of an urn, we may have to discuss whether there should be a memorial concert or memorial service after we die. So we’ll have to have that conversation at some point,” Brit Renanger says.

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

See more content from NTNU:

-

Why is nothing being done about the destruction of nature?“We hand over the data, but then it stops there"

-

Researchers now know more about why quick clay is so unstable

-

Many mothers do not show up for postnatal check-ups

-

This woman's grave from the Viking Age excites archaeologists

-

The EU recommended a new method for making smoked salmon. But what did Norwegians think about this?

-

Ragnhild is the first to receive new cancer treatment: "I hope I can live a little longer"