THIS ARTICLE/PRESS RELEASE IS PAID FOR AND PRESENTED BY UiT The Arctic University of Norway - read more

Can bilingualism help keep you young and healthy?

We all understand that being able to speak two languages fluently is an advantage. But researchers have found that there may be other benefits to bilingualism.

Researchers at UiT have looked at the effect bilingualism has on the brain's structure and function throughout life, and how the metabolism in the brain is affected by bilingualism. These neurochemical changes could underlie and drive neurocognitive adaptations in the brain.

It turns out that if you are bilingual, your brain can be protected against some effects of aging.

“Being bilingual is cognitively demanding, and the brain changes to accommodate this,” says associate professor Vincent DeLuca from the Department of Language and Culture at UiT.

He explains that there is a connection between the language experience, i.e., how much you use the language, neurochemicals or metabolite levels in the brain, and neural adaptation.

Together with colleagues, Professor Jason Rothman and postdoctoral researcher Toms Voits, they have recently published results of their study conducted in collaboration with the University of Reading (UK).

Active language use leads to better neurocognitive protection

The researchers included 79 people in the study, who were between 19 and 83 years old. Some were bilingual and some monolingual. Everyone spoke English, and the bilinguals spoke English and an additional language.

DeLuca explains that as you get older, your brain gradually breaks down, to varying degrees.

“Our findings show that the trajectory of cognitive aging is different for bilinguals compared to those who only speak one language. Bilingualism seems to help the brain to maintain its structure and function,” says DeLuca.

The researchers found a greater advantage among the active bilinguals, i.e., those who use both languages daily.

“It turns out that if you are bilingual, and especially if you use both languages regularly, then this protects the brain against the cognitive aging that happens in the brain naturally. It protects the brain in the same way as, for example, exercise,” says DeLuca.

Still, just like with regular exercise, one must use both languages actively to get the greatest benefit from the brain.

Chemistry drives structural change

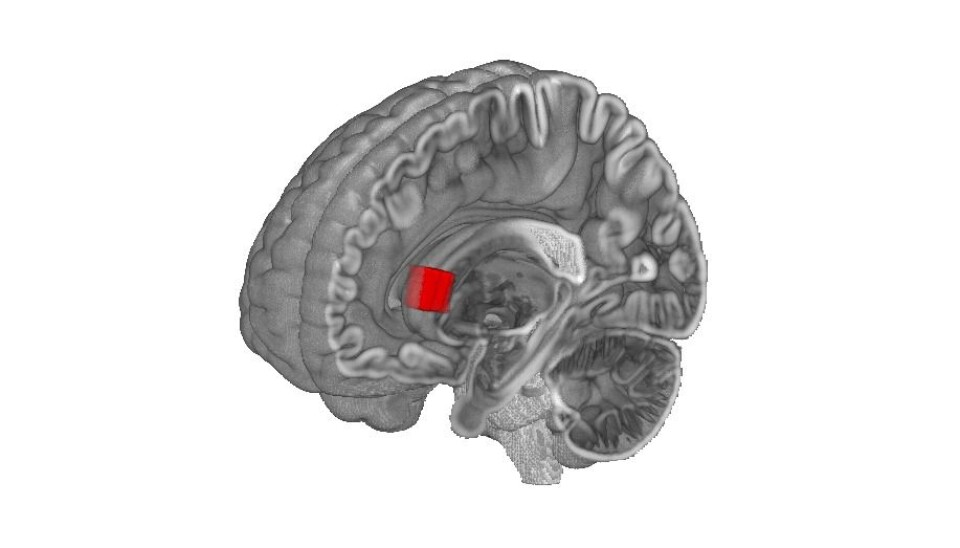

Using MRI spectroscopy (MRS), which is a type of MRI scan of the brain, the researchers have examined subjects brain chemistry, in particular brain metabolites. These are chemicals in the brain that, among other things, underlie changes in the structure. The researchers have found that the concentrations of these metabolites seems to be affected by bilingualism.

“We are one of the first research groups to use this type of method to look at bilingualism. We employed this method to examine metabolite concentrations in certain parts of the brain,” says DeLuca.

He explains that MRS is based on electromagnetism. It targets pre-defined regions of interest with a radiofrequency pulse which allows one to collect information on metabolite concentrations in this area. MRS stands for Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy - it uses an MRI scanner, but instead of getting a structural scan (as you would for medical purposes), you get information that you can use to determine metabolite concentrations in the scanned area.

Previous research has found that speaking two languages can change the structure and function of one’s brain.

“But what is special about our study is that we have gone a step beyond looking at just the structural and functional aspects of the brain and established that bilingualism affects the brain on the level of neural chemistry and metabolism,” says DeLuca.

The brain is efficient

The chemistry is thus directly affected by the fact that you use two languages regularly, and the changes in the chemicals also change the structure and function of the brain.

“But we have found that one must examine bilingualism in a more nuance manner. The engagement with both languages will dictate how much the brain will be affected. Therefore, we have taken a closer look at the extent of bilingual experience on brain metabolite levels.”

DeLuca explains that the brain is always trying to be efficient, and the brain metabolites are involved in this process. Bilingualism and how much one uses the two languages are involved in determining the extent of chemicals and which parts of the brain are affected.

Is it correct then, that the more you use your brain, the bigger and better it gets? Just like a muscle grows if you use it more, for example by lifting weights?

“Yes, you use your brain more to speak two languages. But the brain does not really just grow in size when exercised,” says the researcher.

He explains that the brain will adapt to the experiences it has. Certain parts of the brain will therefore grow, and other parts will shrink. It will try to deal with the challenges it faces in the most efficient way.

“What age when one learns the languages can also have an impact,” says the researcher.

Bilingualism outperforms physical exercise?

DeLuca says that they are in the process of planning a new project in collaboration with the Faculty of Health Sciences at UiT on how, among other things, exercise, diet, and bilingualism affect the brain.

“We want to confirm that bilingualism can be viewed as an isolated factor, which influences the brain in its own right. It may actually be a greater benefit to the brain than exercise is, because of how frequently bilinguals use their languages. It is difficult to physically train all day, but you can speak two different languages throughout the day and thus really challenge your brain,” says DeLuca.

Read the entire research article here: Bilingualism is a long-term cognitively challenging experience that modulates metabolite concentrations in the healthy brain | Scientific Reports (nature.com)

DeLuca, Rothman and Voits are part of the Psycholinguistics of Language Representation (PoLaR) laboratory in the Aurora Center AcqVA at UiT. Read more about the research here: UiT Aurora Center for Language Acquisition, Variation & Attrition: The Dynamic Nature of Languages in the Mind.

See more content from UiT:

-

AI can help detect heart diseases more quickly

-

Why does Norway need its own AI law?

-

Researchers reveal a fascinating catch from the depths of the sea

-

How can we protect newborn babies from dangerous germs?

-

This is how AI can contribute to faster treatment of lung cancer

-

Newly identified bacterium named after the Northern Lights is resistant to antibiotics