THIS CONTENT IS BROUGHT TO YOU BY UiT The Arctic University of Norway - read more

Should you tailor your workouts to your menstrual cycle? Research suggests it may not be that straightforward

There is no specific time in the menstrual cycle where all women have a greater chance of performing better or worse.

Many women experience physical and psychological symptoms that fluctuate throughout their menstrual cycles. Motivation, how ready you feel to exercise, and physical well-being may be affected.

This has led to recent discussions about the potential benefits of planning workouts according to your menstrual cycle.

However, researchers at UiT The Arctic University of Norway have found that the phase of the menstrual cycle does not affect the physical fitness of athletes on a general basis.

None of the measured factors were influenced by the menstrual cycle at the group level.

She emphasises that while you may experience cyclical effects as a woman, not all women follow the same pattern.

Taylor is one of the researchers behind the study and part of the FENDURA (Female Endurance Athlete) project, which is led by UiT. She has mapped how the menstrual cycle affects physical fitness and performance in endurance sports.

Physical tests in different phases

To determine whether the menstrual cycle affects physical fitness, researchers invited female endurance athletes to participate in the project.

The athletes had to have a natural menstrual cycle, meaning they could not use hormonal contraception.

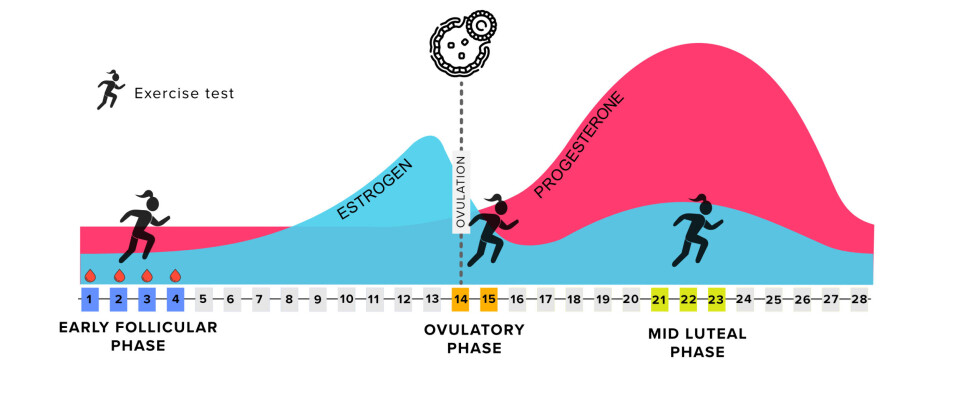

The athletes had to complete tests in three different phases of their menstrual cycle: the follicular phase, ovulation, and mid-luteal phase.

These are phases of the cycle where the amount of the hormones oestrogen and progesterone varies in the body, and one might expect performance to be affected.

In the follicular phase, both oestrogen and progesterone levels are low. Around ovulation, oestrogen is high, and progesterone is low. In the luteal phase, both hormones are elevated.

The tests they conducted are commonly used to assess physical fitness. They provide a very good indication of the athletes' ability to perform.

The athletes were tested in a series of submaximal 5-minute intervals with a gradual increase in speed, a 30-second full-effort double-pole ski ergometer test, and a maximal incremental treadmill running test, where the athletes had to run faster and faster until they could no longer continue.

The researchers measured oxygen uptake, blood lactate, and time to exhaustion.

Some performed better, some worse

“None of the factors we measured were influenced by menstrual cycle phase when we look at group level," says Taylor.

However, the researchers observed some individual differences.

This shows that a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach to training around the menstrual cycle is unlikely to be beneficial for a group of athletes.

Instead, individualised plans should be developed, if necessary, that align with each person's symptom patterns.

“The only way to train meaningfully according to your menstrual cycle is to log your own cycle and understand how it affects you as an individual,” says Taylor.

Currently, there is no evidence to support the idea that menstrual cycle-based training programmes are an effective strategy, especially if it involves using a specific plan for a group of athletes with the intention of optimising performance.

For instance, the idea that everyone should train harder during the luteal phase compared to the follicular phase to achieve better adaptations to the training sessions is not accurate.

“Our research shows that when we look at a group of women, there is no indication that physiological requirements for exercise change throughout the cycle. At least not in the same way for everyone. Some women may have better endurance in the follicular phase, while some are better in the luteal phase. Many probably have no noticeable effect,” says Taylor.

An important research finding

The fact that the researchers found no effect of the menstrual cycle at group level is an important finding for research in general.

“In research, this is important because women have often been excluded as participants from sport science research for fear that fluctuations from the menstrual cycle will affect the testing outcomes. Our findings mean that we can include women in research studies. The menstrual cycle will not affect the results,” says Taylor.

She explains that while there is no clear pattern at the group level, women at the individual level may experience a lot of pain, changes in motivation, and even sleep disturbances.

Therefore, it is important to distinguish between group effects and individual effects.

“Women experience changes throughout the menstrual cycle, but for the most part they probably don't experience the same thing at the same time. But on an individual level, women do experience things. Some women feel worse when they bleed, but some actually feel at their best,” says Taylor.

Nevertheless, there is still a bias in who is willing to join the study. Some women might not want to undergo such demanding tests during different phases of their cycle.

Taylor adds that it's not fun to perform difficult tests if you're suffering from cramps.

What is a normal cycle?

Broadly speaking, Taylor believes we need to find out more about what constitutes a normal menstrual cycle. There is so much we don't know, both when it comes to ovulation and the rest of the cycle.

“For example, is it normal to have 12 ovulations in a year, or is it normal to skip an ovulation? Some women have pain around the menstruation, while other women also feel pain during ovulation. Other women have sleep problems related to their cycle. There are a lot of different things going on,” says Taylor.

Now we have statistical models and artificial intelligence, tools that can be used to understand this better.

“To get more insight on this, we need a large number of women who track their menstrual cycle over a whole year. Only then can we find out what is normal and what is problematic,” says the researcher.

Taylor mentions that a significant finding in their study was that nearly 40 per cent of the participants had a menstrual disturbance. They were subsequently excluded from the study.

“We started with 74 participants and ended up with 21,” she says.

Training planning

Given that there’s no clear pattern to base training on the menstrual cycle, how should coaches approach planning for athletes or teams?

Scheduling training according to the menstrual cycle for an entire team is impossible. And according to Taylor's research, it doesn't even make sense.

She emphasises that the effect of the menstrual cycle is very individual. Some people may experience very strong effects both physically and mentally. If this is the case, coaches should be open to adapting the training accordingly.

“But the menstrual cycle is also an important indicator of health and well-being, which gives a warning signal if something is wrong. Therefore, it's good to know what's normal for a woman's body. Because if things change, then we know something is wrong,” says Taylor.

Reference:

Taylor et al. 'Menstrual Cycle Phase has no Influence on Performance-Determining Variables in Endurance-Trained Athletes: The FENDURA Project', Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 2024. DOI: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000003447 (Abstract)

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

This content is paid for and presented by UiT The Arctic University of Norway

This content is created by UiT's communication staff, who use this platform to communicate science and share results from research with the public. UiT The Arctic University of Norway is one of more than 80 owners of ScienceNorway.no. Read more here.

More content from UiT:

-

AI can help detect heart diseases more quickly

-

Why does Norway need its own AI law?

-

Researchers reveal a fascinating catch from the depths of the sea

-

How can we protect newborn babies from dangerous germs?

-

This is how AI can contribute to faster treatment of lung cancer

-

Newly identified bacterium named after the Northern Lights is resistant to antibiotics