THIS ARTICLE/PRESS RELEASE IS PAID FOR AND PRESENTED BY NTNU Norwegian University of Science and Technology - read more

Researchers will investigate Norwegian fjords using a 10,000 USD underwater robot

A specialist in seabed monitoring brings knowledge from Australia to Norway. The aim is to keep a close eye on the underwater environment.

Oscar Pizarro is a marine robotics researcher. He wants to make continuous monitoring of the seabed easier and less resource-intensive.

In Australia he has been part of a research team that maps and monitors the seabed in the tropical and temperate reefs with autonomous underwater vehicles.

This research has allowed marine scientists to characterise the seabed environment and its changes.

These changes can be part of natural variability but can also be connected to human activities such as pollution, the introduction of invasive species and be related to climate change.

Now he wants to map and monitor the seabed along the Norwegian coastline and in the Arctic.

New prototype with promising results

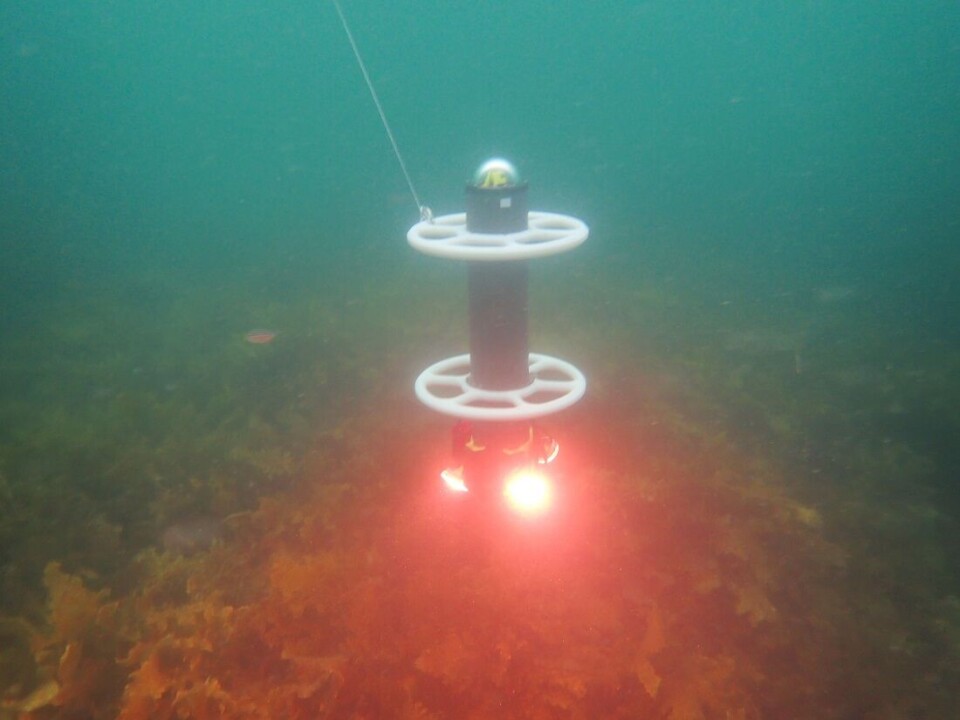

Pizarro is about to develop an autonomous vehicle that costs less than 10,000 USD, which is a lot cheaper compared to the existing subsea robots that are used to map the ocean environment.

This job is one of the things he has brought with him to Norway.

“Can we scale up observations by making the robots cheaper and easier? Today when we use robots to study the environment it’s a relatively complex undertaking, and requires expensive and scarce resources like ships, trained people, and sophisticated machines. It becomes too expensive to collect enough data to really understand the environment,” he says.

Pizarro has been testing this newly developed autonomous subsea robot in Ny Ålesund, Svalbard and in the Trondheimsfjord, the location of the world’s shallowest cold-water coral reefs.

Easier to take risks

The robot is still a prototype, but so far it looks promising.

“Pizarro is a pioneer in optical imaging of the seabed and has made huge contributions in photogrammetry, navigation and picture processing,” Martin Ludvigsen says.

Ludvigsen is one of the researchers at NTNU’s AMOS (Autonomous Marine Operations and Systems), which is a Norwegian Centre of Excellence, and manager of AUR-Lab (Applied Underwater Robotics Lab).

“With cheaper prototypes we can have more robots and risk a bit more with them.” Ludvigsen points out.

We need to map the ocean

NTNU has provided Pizarro research grants for 2.5 years, so he can contribute to ongoing projects with mapping of the marine environment in the Arctic, Lake Mjøsa, which is Norway’s largest lake, the Trondheimsfjord, and several other places.

This mapping is important to give researchers an overview of the effect of human activities on oceans and lakes.

Pizarro’s previous work has contributed to high-resolution, three-dimensional visual maps of the seabed in Australia, and other parts of the world, made on multiple scientific expeditions.

“This work has been used by marine scientists and especially marine ecologists. Single images don’t cover much ground, but if you combine many, you give a picture of the conditions on the seabed, you see patterns at broader scales and yet still at high resolution,” Pizarro says.

The plan is to take this ocean research to the next level at AMOS.

Pizarro is fascinated by the observational pyramid that NTNU AMOS has been working on. This kind of ocean observation is where scientists map areas using small satellites, drones, and both surface and subsea autonomous vehicles.

“Using an observational pyramid means we can collect a lot more data. This could help plan the deployments of these simple robots and complement the observational pyramid with new observations,”Pizarro says.

Continuous monitoring of the seabed

When Pizarro started his work in Australia, the Field Robotics Centre subsea focus was relatively new.

The ability to precisely revisit sites allows marine scientists to directly observe environmental changes after events such as coral bleaching from heat waves.

“We did this research with a group of fantastic students and some talented engineers and turned it in to an operational seabed observation and monitoring program around Australia,” he says.

Through repeated observations every year or every two years, they have monitored changes on the seabed and how different species grow, die, or move.

So, why didn’t he just continue with this well-established research?

“This research is continuing, but as an operational monitoring programme, and there is less room for big changes. I want to develop new robots that can observe the ocean environment even better and see how we can collect data in cheaper and more efficient way,” he says. “NTNU and Trondheim are a hub for research and innovation in marine technology, so it seems like a great place to make big advances.”

Read more content from NTNU:

-

Fish farming is least harmful to the seabed in the north

-

Study: Centralising hospitals has reduced birth mortality

-

Early testing of schoolchildren: “We found absolutely no effect”

-

This determines whether your income level rises or falls

-

Why is nothing being done about the destruction of nature?“We hand over the data, but then it stops there"

-

Researchers now know more about why quick clay is so unstable