THIS CONTENT IS BROUGHT TO YOU BY NTNU Norwegian University of Science and Technology - read more

Artificial nose can sniff out damaged fruit and spoiled meat

This nose has already proven capable of detecting food that has gone off. Now it’s on the trail of diseases.

Although smell has historically played an important role in the fight against diseases such as the plague and tuberculosis, the human nose is generally not sensitive enough to be used as a reliable diagnostic tool.

However, a new artificial nose inspired by our sense of smell could now make it possible to detect undiagnosed diseases, hazardous gases, and food that is starting to spoil.

And it is all made possible with technology that already exists.

Surrounded by antennas

What do your mobile phone, computer, and TV have in common? Antennas.

“We are literally surrounded by technology that communicates using antenna technology,” says Michael Cheffena.

He is a professor of telecommunications at NTNU. Cheffana believes this technology can be used for far more than just communication:

“By giving the antennas sensor functions, the existing infrastructure can be used in new areas of application. This has been one of the main motivations for investigating whether antennas can be used for these purposes,” he says.

The simplest solution is often the best

Previous attempts to create so-called electronic noses have not had the advantage of having an existing infrastructure readily available.

They have also been affected by a number of other challenges that antenna technology can potentially resolve, Cheffena explains.

“Other electronic noses can have several hundred sensors, often each coated with different materials. This makes them both very power-intensive to operate and expensive to manufacture. They also entail high material consumption. In contrast, the antenna sensor consists of only one antenna with one type of coating,” he says.

"That must surely come at the expense of accuracy and functionality?"

Quite the opposite, says Yu Dang. He is a researcher at NTNU's Department of Manufacturing and Civil Engineering.

The smell of petrol and freshly cut grass

According to Dang, their sensor distinguishes between the various gases it has been tested on with an accuracy of 96.7 per cent. This is a result that is not only on par with the performance of the best electronic noses to date.

In some areas, it even surpasses them.

To understand how, we will explain a little bit about how the antenna nose actually works:

The antenna transmits radio signals at a range of different frequencies into the surroundings. It then analyses how they are reflected back. The way the signals behave changes based on the gases present, and because the antenna transmits signals at multiple frequencies, the changes create unique patterns. These can be linked to specific volatile organic compounds.

Volatile organic compounds are gases that are commonly found in the air. They are characterised by a low boiling point, meaning they tend to evaporate at low temperatures.

And even though they can neither be seen nor felt, you will definitely have smelled several of them.

All living organisms emit volatile organic compounds. This includes plants. Often, they do this as a means of protecting themselves from pests or communicating with one another. The smell of freshly cut grass is a well-known example of this.

The petrol fumes from your lawnmower is another example. Since many of the products we use and the materials we surround ourselves with also emit volatile organic compounds, a large number of gases in various combinations will be present in most environments.

This makes the task of distinguishing significant gases from insignificant ones extremely challenging.

It becomes even more difficult when isomers are also added to the mix, Dang explains.

The difficult twins

“Isomers are chemical compounds that have the same molecular formula, but where the atoms are bound together in slightly different ways,” he says.

According to the researchers, they are a bit like twins: Very similar, yet not identical.

“These compounds have long been a challenge for this type of sensor technology. Even the most sophisticated e-noses consisting of many different sensors struggle with them,” says Dang.

He is therefore very pleased that their antenna sensor performs so well even on these difficult compounds.

May be able to detect disease

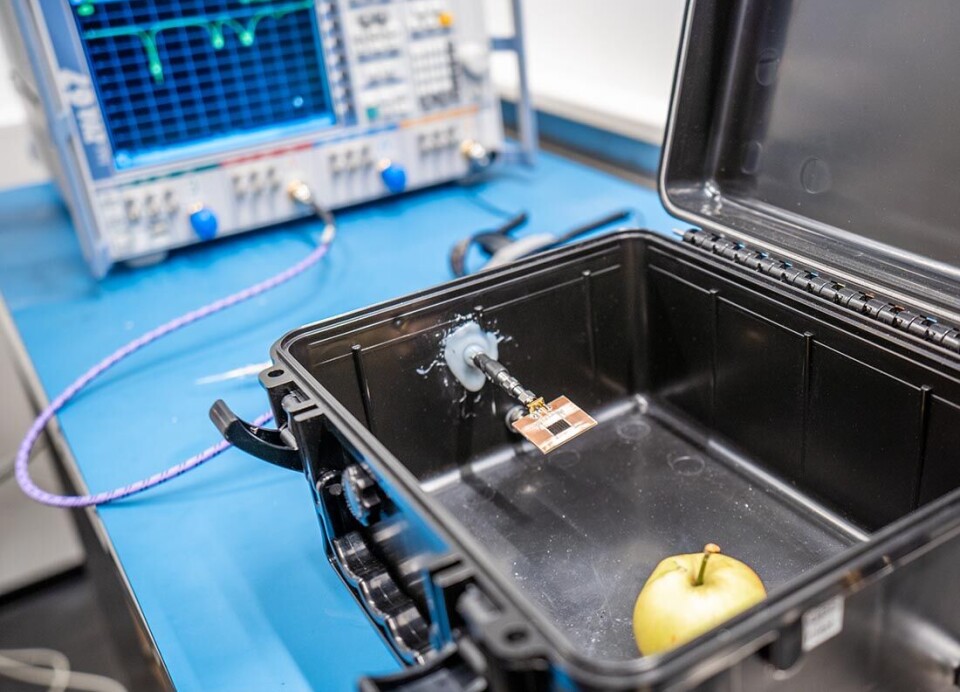

So far, the sensor technology has been tested on impact-damaged fruits and meats of varying ages.

By adjusting the algorithms that detect the unique ‘fingerprints’ of the different gases, the researchers believe the technology may also be able to smell diseases.

“Volatile organic compounds enable trained dogs to detect health-threatening changes in blood sugar and diseases like cancer, so the principle is largely the same,” Dang says.

Unlike dogs, however, the antenna sensor does not require months of training or specialised handlers to be used. The basic technology is something you already have in your living room.

Reference:

Dang et al. Facile E-nose based on single antenna and graphene oxide for sensing volatile organic compound gases with ultrahigh selectivity and accuracy, Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical, 2024. DOI: 10.1016/j.snb.2024.136409

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

More content from NTNU:

-

Why is nothing being done about the destruction of nature?“We hand over the data, but then it stops there"

-

Researchers now know more about why quick clay is so unstable

-

Many mothers do not show up for postnatal check-ups

-

This woman's grave from the Viking Age excites archaeologists

-

The EU recommended a new method for making smoked salmon. But what did Norwegians think about this?

-

Ragnhild is the first to receive new cancer treatment: "I hope I can live a little longer"