An article from University of Oslo

Due process of law toned down in international criminal courts

It can be easier to convict political leaders if the fundamental values of criminal law are given low priority

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

You've probably heard the statement "innocent until proven guilty" on television crime shows, but this principle is among the most fundamental when it comes to the practice of criminal law in a country governed by the rule of law – such as Norway.

We are all also equal before the law, and we punish people for what they themselves have done and for the consequences of their actions. We don't punish people for crimes committed by others who happen to belong to the same ethnic group as the individual in question.

International criminal law is founded on the idea that those who have committed serious crimes will not escape justice and will be punished. Punishment is society’s way of expressing its disapproval of a criminal act.

Given these basic principles, are there situations where it is acceptable to adhere to them less strictly? What if this makes it easier for the prosecuting authority to obtain the conviction of a political leader whom they believe has taken part in serious international crimes?

A clear ‘No’

Torunn Salomonsen's answer to these questions is a clear ‘No’. She recently defended her thesis at the University of Oslo on the international criminal courts’ use of an alternative theory, called the Joint Criminal Enterprise theory, to enable them to more easily convict political leaders who have committed international crimes.

“International criminal courts must pay more attention to the fundamental values that criminal law is based on when they develop the law. If they don’t, we run the risk of developing a model of criminal law that doesn’t deserve to be called constitutional,” she says.

Joint Criminal Enterprise is one of the key theories of liability that has increasingly been used to hold political leaders from the former Yugoslavia responsible for international offences. The theory, often called JCE, is applied in situations where two or more persons have a joint plan or intention to commit a crime, and where both or all of them take part in putting the plan into action.

Wide international recognition

The theory was used first in contemporary times in 1999 by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) in the appeal proceedings against Dusko Tadic, the Bosnian Serb war criminal.

“Tadic was not a political leader, but the ‘JCE’ theory of liability turned up for the first time in this case. One of the prosecutors was smart enough to realise that the theory had a lot of advantages and that it could also be used in other cases to get political leaders convicted. Probably there was also a little bit of creativity and chance that enabled them to see the theory’s potential.”

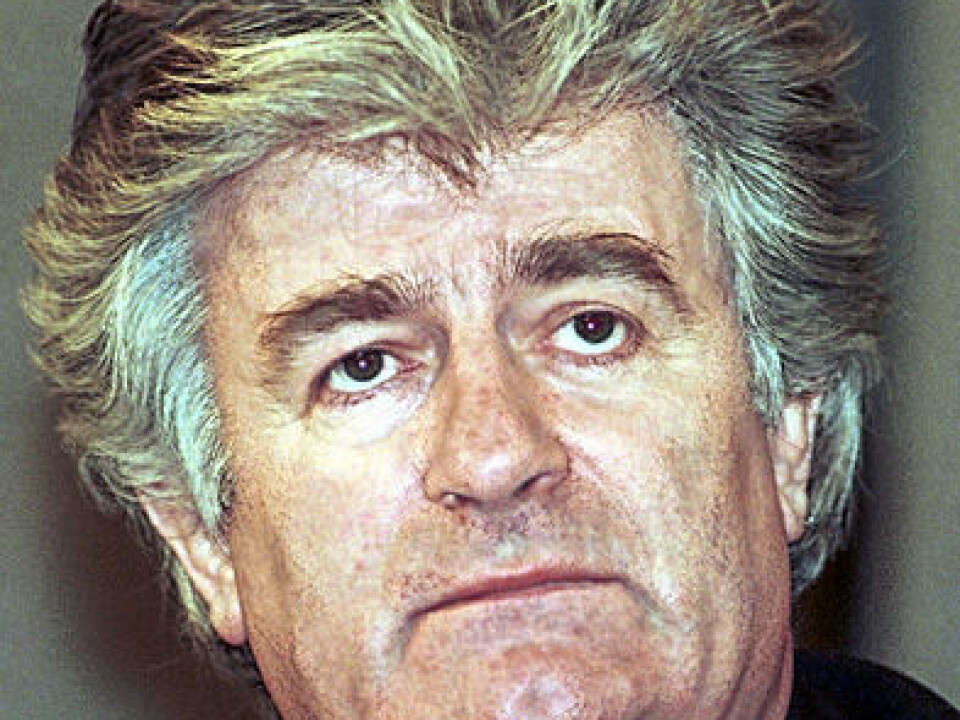

Since then the theory has received wide recognition in international criminal law and has been used in several cases – for example that against Milan Martic, the Croatian Serb politician who helped organize an ethnic cleansing campaign of Croats and other non-Serbs from Krajina. It was also decided to bring criminal charges against Radovan Karadzic on the basis of this theory.

Tension and concerns

Salomonsen points out that tensions have arisen between making certain that those who have committed horrible crimes do not evade conviction and punishment and ensuring compliance with the founding principles of states governed by the rule of law.

At the same time, Salomonsen’s research also shows that a broad interpretation of JCE challenges the principles of criminal law that are central to liberal criminal law traditions. She says that none of the alternative theories of liability that are in use are as problematic - at least not to the same degree.

Easier to prove guilt

Salomonsen says it is often easier for prosecuting authorities to prove guilt under the JCE theory.

“For example, the accused can be held responsible for all the crimes committed by other participants in a joint criminal enterprise. The prosecuting authorities don’t need to prove in each individual case that the crimes are a consequence of the accused’s own actions. In the Tadic case, for instance, the accused were convicted of certain murders even though no proof was found to show that these murders were a consequence of something Tadic himself had done. The justification was that the murders were a natural consequence of a plan involving the so-called ethnic cleansing of the Prijedor area, which Tadic had been involved in to only a small extent.”

“By using JCE, the court could also hold political leaders responsible for more crimes or for more serious crimes than alternative theories of liability permit. And that’s why the theory’s popular,” says Salomonsen.

“Some people also claim that it’s easier for political leaders to escape justice when liability theories other than JCE are applied in court. It may be that the main prosecutor in the ICTY was a bit more persistent and aggressive in his strategy against letting off those responsible for international crimes, and that this governed the choice of theory more than making sure that the prosecution was following the founding principles of states governed by law.”

Another motivation may also have been the desire to promote goals such as peace, reconciliation and accountability through the deterrent effect that punishment can have.

Not the best theory to use?

Salomonsen’s research nonetheless shows that there is no basis for claiming that political leaders will escape criminal prosecution if other theories of liability are used.

“The tribunal in Rwanda used other theories that are not as problematic – as has the permanent international criminal court. These theories may also ensure that political leaders are held responsible, although JCE is regarded as a more effective strategy that makes it easier to get them convicted. Even in the ICTY other theories of liability have led to convictions in cases against political leaders, as in the case against Radoslav Brdanin.”

“With this in mind there’s good reason to be critical of the use of JCE. It’s not very likely that a broad interpretation of JCE will lead to peace and reconciliation or deter others from committing international crimes,” she says.

--------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no