THIS ARTICLE/PRESS RELEASE IS PAID FOR AND PRESENTED BY University of Oslo - read more

Norway is strengthening the position of minority languages

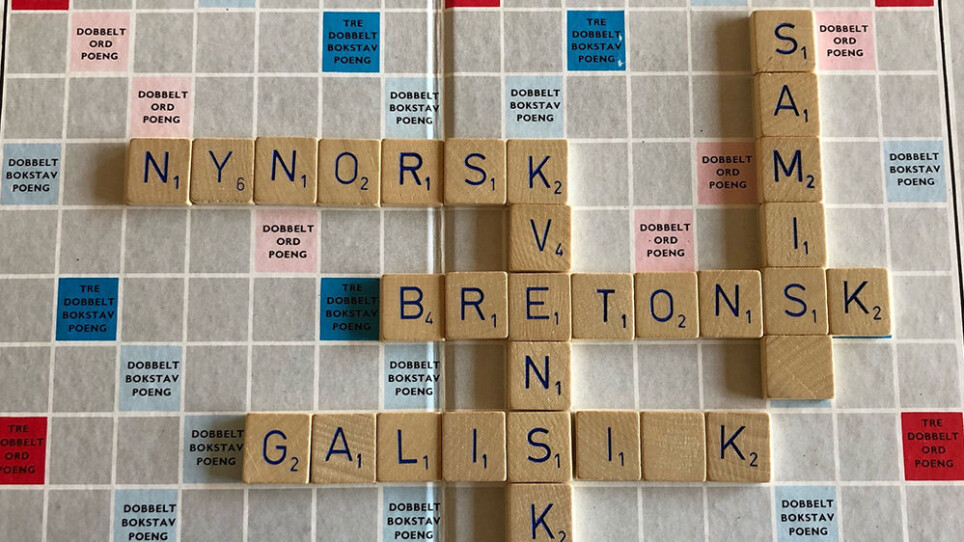

Many European minority languages are being elevated within legislation and research. Linguistic Minorities in Europe aims to make the research available.

Speaking more than one language is far more common than speaking just one. But although many people learn foreign languages to traverse the world and get to know other people, most of the languages we speak are small.

“It is a myth that Norwegian is a small language. In fact, it belongs to the ten percent of languages spoken by the most people,” says Pia Lane, professor of multilingualism at the University of Oslo.

Used by well over 5 million people, and enjoying the status as a national language, Norwegian is far from threatened. In Europe, there are on the other hand up to 100 minority languages, including the six Norwegian minority languages: Northern Sami, Southern Sami, Lule Sami, Kven, Romanes and Romani.

The position of these languages in the Norwegian Language Act has now been strengthened. The same applies to Nynorsk, which is no longer considered a language form, but as a separate language.

Nynorsk is a separate language

In the Language Act recently adopted by the Norwegian Parliament, multilingualism is discussed in an explicitly positive manner, and the position of minority languages is strengthened. A significant change has also been made for Nynorsk and Norwegian Sign Language.

“We are no longer talking about Nynorsk and Bokmål as two forms of the Norwegian language, but as separate languages,” says Unn Røyneland, professor at the Centre for Multilingualism (MultiLing) at the University of Oslo.

With the Equal Status Act in 1885, it was decided that Nynorsk was to be equal to Bokmål. That this new law has been passed almost 140 years after this, is better late than never, thinks Røyneland.

“A language is not just defined linguistically. There is a historical, political, cultural and social dimension, which is significantly connected to emotions and identity,” she says.

“The Nynorsk written language has gradually acquired a large and important literary tradition and rich cultural history, and it is now considered more than just a way to write Norwegian.”

The languages spoken by a small group are often in what researchers call a 'minoritised' position. This means that they have been turned into minorities, which can lead to marginalisation and neglect.

“Nynorsk faces many of the challenges faced by other minority languages, even though it has long been deemed equal with Bokmål according to the law,” says Røyneland.

Therefore, the professor is pleased to see that Nynorsk will be strengthened. The same applies to Norwegian Sign Language.

“Now, sign language will not just be seen as an auxiliary language, but as a separate, full-fledged language that relates to culture and identity,” she says.

European cooperation on minority languages

In Europe, minority languages are protected by national legislation corresponding to the Norwegian Language Act. As one of 25 countries, Norway has ratified the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. Doing this, Norwegian authorities make it clear that the protection of the six languages: Northern Sami, Lule Sami, Southern Sami, Kven, Romani and Romanes, helps to maintain and develop cultural wealth and traditions within Europe.

“I think few people are aware of how multilingual Europe has always been,” says Pia Lane, who often encounters the notion that European citizens speak only one, perhaps two, languages.

Lane represents Norway in the Expert Committee for The European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages, and recognises clear differences between the European countries.

“The charter is based on good will, and relies on countries being willing to promote minority languages. This absolutely applies to Norway, where the Sami languages have long been in a unique position. We are now also considering whether to commit to giving the other languages a similar elevation. Other countries such as Sweden and Montenegro have also done a good job.”

Research can elevate languages

Among researchers, Nynorsk has long been considered a minority language. Therefore, it is also included in Linguistic Minorities in Europe, a digital resource that Unn Røyneland, Pia Lane and Lenore Grenoble launched in the autumn of 2020.

Its aim is to gather academic resources, such as peer-reviewed overview and research articles, but also audio and video clips, for minority languages in Europe on one single website.

“Some of these languages have become minority languages when new borders have been drawn between states,” says Lane.

This applies to, for example, German in Denmark, or Kven and Meänkieli, that were spoken in multilingual areas which have become a part of Norway, Sweden and Finland.

“Conversely, think about the larger language Hungarian, which was the imperial language of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and was therefore spread throughout many countries.”

Others have become minority languages after people have migrated.

“This applies to, for example, Turkish, which is widely spoken in Germany and the Netherlands, and Polish, which is now used in many countries within Western Europe.”

According to Lane, when languages are spoken within a new context over many years, they will change. The researcher herself is from Northern Norway, and had Finnish as an elective course at school.

“For a while, we used books that were made for immigrants to Finland. Just imagine when people in Northern Norway learn languages with materials made for Pakistanis who have just arrived in Helsinki. The context is completely different – for example, we had little need to learn cultural codes for how to greet people,” she points out.

Languages open doors

Although some languages are spoken by few people, preserving them has a value, Lane believes.

“The numbers are not necessarily important. Whether you are using a language spoken by 100, 10,000, or millions of people— you will not associate with 10,000 people anyway.”

The professor reminds us that it is not only the widely spoken languages that takes us out into the world.

“Languages open the door to our neighbouring countries. Sami is spoken in Sweden, Finland and Russia. With Kven, you can understand Finnish neighbours and those who speak Meänkieli, plus, you are at a good starting point for learning Estonian,” she says.

For researchers, insight into one minority language may have a transferable value for research on another, Unn Røyneland points out.

“For example, if you write about Galician in Spain, it is interesting to know how the educational system works for other minority languages elsewhere in Europe. Through Linguistic Minorities in Europe, this research is readily available,” she says.

A new digital resource for minority languages in Europe

According to Røyneland, research into minority languages is rarely a high priority for national authorities. Therefore, this database is a step forward for the research field.

“A well-known challenge is that the dissemination of research is very fragmented, throughout individual articles in various academic journals. Here, we are gathering articles and resources across the disciplines linguistics, pedagogy, history, psychology and anthropology,” she says.

Sami and Basque are some of the languages that are widely researched. Therefore, they are among the first languages to included in Linguistic Minorities in Europe, together with Turkish, Hungarian, Frisian and Croatian. Eventually, the website will be supplemented with research in a number of other languages.

“This way, you can find connections and draw parallels between various languages.”

Pia Lane points out that connections that testify to the development of languages are constantly emerging.

“When we see that there is close contact between Scotland, Ireland, Spain, Portugal and France, it is not so strange, because the coastal areas were Celtic. For example, the Breton language, which is a minority language in France, is Celtic, and related to Irish and Welsh,” she says.

According to Lane, this demonstrates how some languages have become minority languages:

“We think of Europe in terms of national borders, but the long, deep, historical ties, they go beyond and across borders.”

Learning from past mistakes

As research on minority languages becomes more accessible, it may become possible to learn from past mistakes in language policy. One example is the Norwegian policy towards Sami and Kven people, which Pia Lane places within the context of monolingual ideology, and links to social problems.

“The population in the North used to have worse results at school and poorer levels of successful completion. The exception for the schools was those who had the Sami school schedule, where the results were better.”

According to the researcher, people need to be allowed to speak the language that they know best.

In recent years, many small languages have experienced a boost, and the researchers are witnessing a completely different interest in Sami and Kven than before.

“With new and social media, young language users in particular are connecting across borders and helping to revitalise their languages,” says Lane.

See more content from the University of Oslo:

-

Mainland Europe’s largest glacier may be halved by 2100

-

AI makes fake news more credible

-

What do our brains learn from surprises?

-

"A photograph is not automatically either true or false. It's a rhetorical device"

-

Queer opera singers: “I was too feminine, too ‘gay.’ I heard that on opera stages in both Asia and Europe”

-

Putin’s dream of the perfect family