THIS ARTICLE/PRESS RELEASE IS PAID FOR AND PRESENTED BY the University of Bergen - read more

Natural temperature fluctuations not to be confused with reduced warming

Researcher warns against interpreting reduced temperature increase as a sign of climate change slowing down.

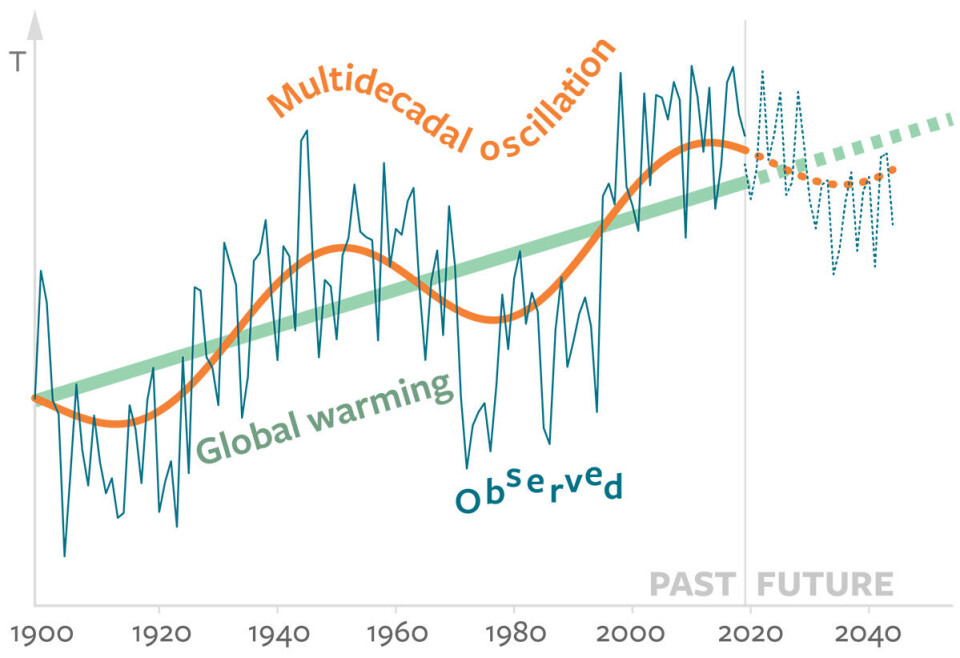

Over the last century, sea surface temperatures in the North Atlantic have oscillated, that is to say they have fluctuated in a regular rhythm, over periods of a few decades. These oscillations have not been limited to the ocean.

Corresponding variations have been observed in the Arctic sea ice cover, in ocean currents and in the air up to the stratosphere, more than 10 kilometres above the ground.

During the winter months in the Northern Hemisphere, the variations are large enough to affect global temperatures. Some decades are warmer than others.

A hiatus in global warming in the 1950s through 1970s and a subsequent increase in the 1980s through 2000s, can be linked to this oscillation. We are now again in a period where conditions in the North Atlantic indicate that it should get colder.

Research can be misinterpreted

“The oscillations can temporarily dampen anthropogenic warming, but it cannot give us back the climate of the 1950s, 60s and 70s,” Nour-Eddine Omrani says.

Omrani, a researcher from the Bjerknes Centre and the University of Bergen, was the lead author of an article about the mechanism behind the oscillations in the North Atlantic region. Researchers from Germany, Italy and the USA contributed to the study, together with several of Omrani's colleagues in Bergen.

Omrani now warns against misinterpretations of their results.

A reduced temperature rise in the coming years does not mean that global warming has slowed down.

Global warming makes both cold and warm phases of the oscillation warmer. In cold phases, less sea ice will disappear than in warm phases, but in either case, more sea ice will melt now than fifty years ago.

Temperatures will accelerate again

“The next multidecadal warming will start from a higher level and lead to unprecedented warming and associated extremes,” Omrani says.

He hopes we will use the coming years wisely.

“The present and predicted hiatus offer time to work out technical, political and economic solutions before the next accelerated global warming,” he says.

Oscillations make the climate more predictable

The recent study showed that the oscillation in the North Atlantic is reasonably predictable, allowing for practical applications.

Oscillations like the one in the North Atlantic makes it possible to predict weather and climate in the coming seasons, year and decades – longer than weather forecasts and shorter than climate projections.

Temperature variations in the tropical Pacific Ocean, shifting between El Niños and La Niñas, is another such oscillation.

The success of such predictions depends on knowledge of the mechanisms behind the variations, as well as how the ocean and atmosphere are affected. This is a relatively new research field, combining global warming and variations on shorter time scales.

“Without the long-term anthropogenic trends, the evolution of the present and projected near-future climate strongly resembles the colder conditions seen in the 1950s–1970s. Climate change makes the present and projected climate much warmer,” Nour-Eddine Omrani says.

Reference:

Omrani et al. Coupled stratosphere-troposphere-Atlantic multidecadal oscillation and its importance for near-future climate projection, npj Climate and Atmospheric Science, vol/ 5, 2022. DOI: 10.1038/s41612-022-00275-1

This article/press release is paid for and presented by the University of Bergen

This content is created by the University of Bergen's communication staff, who use this platform to communicate science and share results from research with the public. The University of Bergen is one of more than 80 owners of ScienceNorway.no. Read more here.

See more content from the University of Bergen:

-

The proteins in your blood can reveal early signs of heart problems

-

Electricity against depression: This may affect who benefits from the treatment

-

Quantum physics may hold the key to detecting cancer early

-

Researcher: Politicians fuel conflicts, but fail to quell them

-

The West influenced the Marshall Islands: "They ended up creating more inequality"

-

Banned gases reveal the age of water