THIS ARTICLE/PRESS RELEASE IS PAID FOR AND PRESENTED BY The Norwegian School of Sport Sciences - read more

Monitoring youth athletes could reduce the risk of injuries

Many sports injuries – and the risk factors involved in developing them – are overlooked by coaches. In order to reduce injuries and dropouts, training should be more adapted to accommodate growth and maturity than is currently the case.

You have probably noticed this yourself: teenagers grow at different times and at different rates. Some quickly become muscular, others suddenly grow tall and skinny. Girls mature well before boys.

However; what if different parts of the body mature at different rates? If this is the case, the most vulnerable body parts, the weakest links, will also vary over time.

“This is something coaches need to take into account. At the same time they need to know which injuries are most common and have the greatest impact. There is a lot of room for improvement here.”

Vulnerable phases

These are the words of Eirik Halvorsen Wik, who has been studying how various injuries can be linked to different risk factors during one’s adolescent years – or: how injuries can be linked to different stages of growth and biological maturation in elite youth athletes. When there are such differences in maturation within a group, we should not just place emphasis on age when putting together a team or a training group. We will return to that.

One of the aims of Mr. Wik's work has been to answer the question about whether or not the risk of developing injuries is associated with growth and maturation. There is a lot to indicate that they are. One of his findings is that skeletal injuries – one of the most serious types of injury – are under-reported.

Skeletal injuries overlooked

For the past four years, Eirik Halvorsen Wik has been living in Qatar's capital, Doha, working with Aspire Academy, an elite national academy for talented boys between the ages of 12 and 18. He has studied sports injuries in football and athletics, specializing in sprints, endurance, throws and jumps. All these youth athletes have access to physiotherapists on a daily basis, so it has to be possible to record all injuries - both those less and more severe.

The main aim of the Oslo Sports Trauma Research Center with which Wik is affiliated in Norway is to prevent injuries. In order to know where to implement measures, it is necessary to know as much as possible about the injury patterns. This will allow for detection of injuries in the initial stages, implementation of injury-reduction measures – and to ensure continued development for the athlete concerned. This is important for individual progress, in order to prevent long-term complaints and possibly also for whether or not the athlete will be able to continue with his or her sport. It is also important for the team.

In this respect Wik has not only looked at the so-called incidence rate, i.e. how often an injury occurs, he has also looked at how serious the injury is: the injury burden.

“We discovered that skeletal injuries in particular are overlooked. These occur less frequently, so they disappear in the statistics, but they are serious for the athlete. If you look at total injury time, such injuries are more serious than previously reported. Relatively speaking, they are a greater problem in athletics than in football.”

Weakest links change

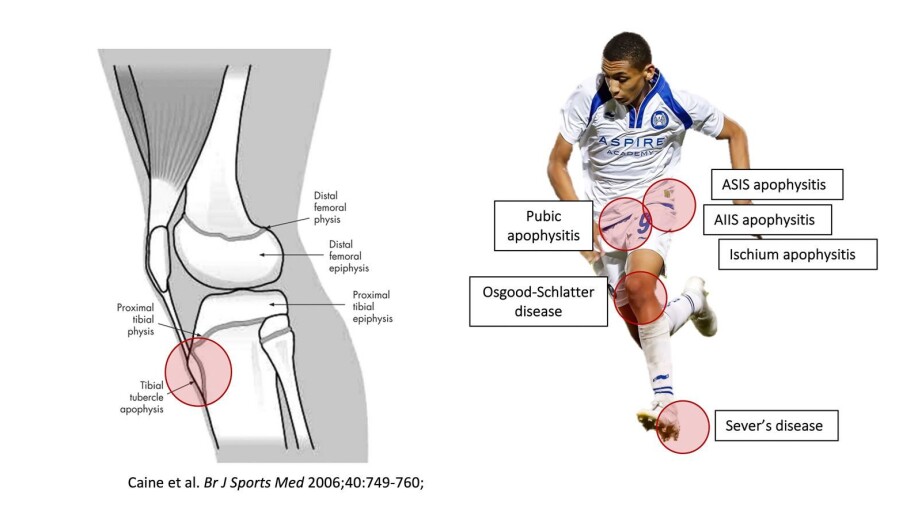

Skeletal injuries do not just include fractures, but also bone stress injuries and irritations to the growth cartilage (growth plates). Such injuries are often found close to where the muscle attaches to the skeleton, and this growth cartilage gradually hardens into mature bone with age. Unlike fractures, such injuries will often only cause pain, so the athlete is able to continue.

“In order to limit such injuries, we should not only take the pain seriously, we should also know that the typical locations of such injuries is age-dependent,” says Mr. Wik.

“The heel is most likely culprit between the ages of 10 and 12-13, and the knee between the ages of 12 and 15, while the bones in the hip and pelvis for many is not fully developed until the age of 20. This applies to boys, while girls develop earlier.”

“But are the 'weakest links' at any one time in one’s development individual as well?”

“Yes, because the structures mentioned develop at such different times between individuals.”

Can monitor growth and maturation

Eirik Halvorsen Wik believes that coaches need to take these changes in the injury pattern into account. However, if we know about the risk factors, then things do not need to be so difficult.

“You can monitor growth or maturation by recording the height of each individual athlete, for example, 3-4 times per year. When puberty and the growth spurt 'takes off', we should be more careful with exercises that have a big impact, especially on the heels, knees and hips,” he says. “At the same time we should be careful about making sudden changes in the training load. Late maturing athletes may be particularly prone in this respect, because the demands of training and competition often increase while they are still in a phase with rapid growth and before they are mature enough to withstand the load.”

Maturation of young athletes can be monitored even more carefully if their so-called bone age is measured, but this requires more advanced equipment. At the same time it would probably be important for a coach to explain to the parents why he/she has adjusted a training programme.

“But that could be difficult, couldn’t it?" They are so keen to do their best at all times.”

“We need to explain why adjustments are important. If they are able to make individual adjustments, it would be a win-win for all concerned.”

Motivating

Keeping an eye on maturation is decisive for retaining athletes in their sport. This is because young people grow and mature at such different times. A 13-year-old who matures early may physically be like an average 15-year old, who in turn could be like a 'late bloomer' at the age of 17.

“Each individual should get the opportunity to compete or train with others at his/her own level, regardless of age, at least every now and then.” Mr. Wik believes that this can be motivating for both early and late maturing athletes, because they are able to pit themselves against others who are equally strong, in respect of both physical challenges and displaying their technical skills. “In some sports, such as martial arts like judo, they already use weight classes within wider age groups.”

However, he stresses that such juggling needs to be carried out carefully. “In this respect coaches also need to explain properly why they are doing it.”

He emphasises that these are ideas inspired by studies elsewhere and might well appear difficult in practice, e.g. for social reasons that might be experienced over time.

Modifying training at the right time

In addition to the incremental maturation and the risk of developing injuries that change over time, Mr. Wik’s studies in Doha show that the injuries sustained by youth athletes occur more frequently with increasing age.

“As you get older, you also get heavier, stronger, and train and compete more, and there is an increase in the load, intensity and power. We have taken training time into consideration, but we haven't measured everything.”

Perhaps more obvious is the fact that the injury types sustained depend on the type of sport. Also in Qatar, sprinters are more likely to develop muscle injuries, throwers develop injuries in the lower limb cartilage and muscles in the upper body, long-distance runners suffer generally from bone stress injuries and jumpers often lose time to stress fractures. “But age and maturation also play a role in this respect. It's all about knowing your athlete and making adjustments at the right time.”

Reference:

Eirik Halvorsen Wik: Injuries in elite male youth football and athletics - Growth and maturation as potential risk factors. Doctoral dissertation under the Department of Sports Medicine at NSSS, 2021. (About the dissertation at NSSS website)

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

See more content from The Norwegian School of Sport Sciences:

-

Football expert wants to change how people watch football at home

-

Kristine suffered permanent brain damage at 22: "Life can still be good even if you don’t fully recover"

-

Para sports: "The sports community was my absolute saving grace"

-

Cancer survivor Monica trained for five months: The results are remarkable

-

What you should know about the syndrome affecting many young athletes

-

New findings on how athletes make the best decisions