THIS CONTENT IS BROUGHT TO YOU BY University of Oslo - read more

New method tested on mice gives new hope for immunotherapy against prostate cancer

So-called cold cancer types cannot be treated with immunotherapy. But a new discovery may make them hot and open to treatment after all.

Over the past 15 years, there has been rapid development in the field of immunotherapy. While traditional cancer treatment attacks cancer cells with radiation, surgery, and chemotherapy, immunotherapy uses a different approach.

“With immunotherapy, the focus is not directly on the cancer cells themselves, but on the immune system within the microenvironment surrounding the tumour. The tumour actually contains not only cancer cells but also a variety of normal cells from the host, such as blood cells and immune cells,” says Fahri Saatcioglu.

He is a professor at the University of Oslo's Department of Biosciences.

He explains that small tumours form in the body every day, which the immune system recognises and removes. But in addition to the part that kills unwanted cells, the system also includes a part that acts as a brake, ensuring the system stops in time and does not start attacking healthy cells.

This brake is called a checkpoint.

Cold cancer types

The trick cancer cells use is to override the normal regulation of the immune system, keeping the brake on at all times. As a result, the immune system senses no danger and allows the cancer cells to grow and spread.

However, in certain types of immunotherapy, drugs are used to override these checkpoints. They prevent them from stopping the immune cells, allowing them to freely attack cancer cells.

Such drugs are called checkpoint inhibitors.

“There are, however, some types of cancer on which immunotherapy does not work. But for the 20–40 per cent of cases where it does, the expected lifespan can increase from just a few months to at least 10–15 years,” says Saatcioglu.

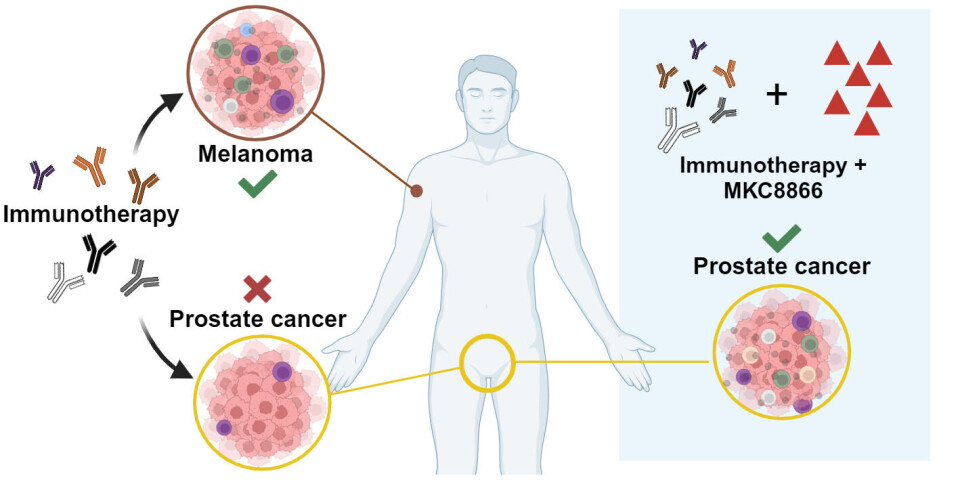

The types of cancer that immunotherapy does not work on are called cold cancers. They include pancreatic cancer, ovarian cancer, breast cancer, and the type that Saatcioglu primarily researches: prostate cancer.

Present in all cells of the body

Prostate cancer is the most common form of cancer among men in Norway. Each year, approximately 5,000 new cases are discovered.

Despite continuous improvements in treatment methods, about one-fifth of patients still die. New treatment methods are therefore highly welcome.

In Saatcioglu's lab, they have previously discovered a potential treatment for prostate cancer. They achieved this by blocking a signalling pathway known as IRE1 with the small molecule MKC8866.

IRE1 signalling is crucial for cells to manage internal and external stress, and by blocking IRE1, cancer cells lose much of this capability.

“But IRE1 is not unique to cancer cells; it exists in all cells in the body. So, what happens to the other cells in a prostate tumour when we use the MKC8866 molecule to block IRE1? Or when we eliminate it using the gene-editing method CRISPR-Cas9?” he asks.

Using a new method called single-cell RNA sequencing, Saatcioglu explains that they have been able to study what happens to all the cells in the tumour's microenvironment.

More immune cells attacking the tumour

“When we blocked the IRE1 signalling, we found that the immunosuppressive effects in the tumour microenvironment were significantly reduced. This led us to hypothesise that this might have a beneficial effect on immunotherapy for prostate cancer," he says.

In other words: Blocking IRE1 could potentially turn a cold tumour into a hot one, making it receptive to checkpoint immunotherapy.

“When we targeted prostate cancer with a checkpoint inhibitor alone, we saw only a small effect. Just blocking IRE1 at a low dose caused a slight reduction in tumour growth, but not much,” says Saatcioglu.

He reports that the combination of a checkpoint inhibitor and IRE1 blockade led to a dramatic reduction in tumour growth in several mouse models.

At the same time, the researchers observed that the composition of immune cells in the microenvironment in the tumours changed to include more immune cells that attack the cancer cells.

Findings relevant for other cancer types

“We have tested and observed the same effect in four different mouse models, so we are very confident in our conclusions," says Saatcioglu.

The next step is clinical trials – trials on patients.

Saatcioglu primarily researches prostate cancer, but it is reasonable to ask whether the same treatment could also be applied to other cancer types classified as cold.

“There are recent studies that suggest this. The IRE1 signalling pathway is, as mentioned, present in all cells, which of course includes other types of cancer cells. There is evidence that our findings are also relevant for other types of cancer,” he says.

Reference:

Unal et al. Targeting IRE1α reprograms the tumor microenvironment and enhances anti-tumor immunity in prostate cancer, Nature Communications, vol. 15, 2024. DOI: 10.1038/s41467-024-53039-1

This content is paid for and presented by the University of Oslo

This content is created by the University of Oslo's communication staff, who use this platform to communicate science and share results from research with the public. The University of Oslo is one of more than 80 owners of ScienceNorway.no. Read more here.

More content from the University of Oslo:

-

What do our brains learn from surprises?

-

"A photograph is not automatically either true or false. It's a rhetorical device"

-

Queer opera singers: “I was too feminine, too ‘gay.’ I heard that on opera stages in both Asia and Europe”

-

Putin’s dream of the perfect family

-

How international standards are transforming the world

-

A researcher has listened to 480 versions of Hitler's favourite music. This is what he found