An article from University of Oslo

Lung cancer is rarely detected by current X-ray examinations

X-ray images reveal only 20 percent of the lung cancer cases. CT images reveal 90 percent.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

In Norway, no other forms of cancer take as many lives as lung cancer. Each year, 2800 Norwegians (out of a population of 5 million) develop the dreaded disease. Their prognosis is unpromising: six out of seven die within five years.

What is especially unfortunate about lung cancer, is that the tumour has ample space to grow. It can thus grow for a long time before being detected.

Most patients have their first diagnosis made by X-ray imaging. Each year, Oslo University Hospital takes 30,000 chest X-rays. Nationwide, this number exceeds one million.

Nobody has ever investigated how well X-ray images function with a view to detecting lung cancer and other diseases of the chest region.

“X-ray technology has remained nearly unaltered for one hundred years,” says Trond Mogens Aaløkken at the Department of Radiology and Nuclear Medicine, Oslo University Hospital.

In cooperation with a group of physicists at the Intervention Centre he has made a comparison of the proportion of patients who obtain a correct diagnosis with X-ray images and how many patients might have obtained a correct diagnosis with computer tomography (CT), which is a far more modern imaging technology.

While X-ray images are two-dimensional, CT images are three-dimensional. CT images can thus reveal the exact location of the tumour.

Too much radiation before

Until today, the radiation dose from examinations of lungs with CT has been one hundred times higher than from regular X-ray examinations. A CT scan is equivalent to five years of natural background radiation.

Radiologists have therefore been reluctant to use CT for an initial diagnosis of lung cancer.

If the X-ray examination is negative, some months may pass before the patient is referred for a CT scan. Then, it may already be too late.

“It’s sad that so many come to be treated too late because the hospitals are reluctant to use CT. The survival rate can be increased significantly if the lung cancer is initially detected by CT,” Aaløkken points out.

In recent years, CT scanners have become far more effective. The mathematical method for reconstructing pictures has changed completely. This means that the images now contain more information, while the radiation dose has decreased.

Little radiation now

Researchers at the Intervention Centre have now succeeded in producing CT images with the same low radiation dose as a regular X-ray image.

“We still cannot achieve the same high-quality images by replacing standard full-dose CT with ultralow-dose CT, but we have wondered whether the old low-quality X-ray examinations can be replaced by ultralow-dose CT. Although the CT dose is nearly as low as for a chest X-ray, we can obtain far more information from the images,” says associate professor Anne Catrine Trægde Martinsen, who works at the Intervention Centre and the Department of Physics, University of Oslo.

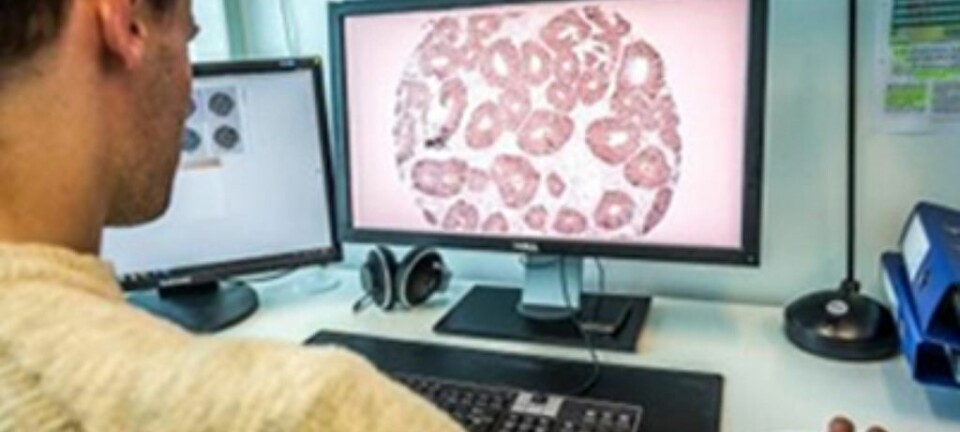

To find out what works best, the researchers have undertaken a pilot study in which they made both X-ray images and ultralow-dose CT images of a small sample of patients for whom the researchers knew the correct answer beforehand.

The radiologists who examined the images did not know what ailed the patients, but they were aware of being part of a research project, and they were told to search for all possible diseases of the chest region.

From 18 to 89 percent hits

The results were remarkable. By studying the X-ray images, the radiologists found the correct answer in only 18 percent of the cases. In other words, they missed 82 percent of the diagnoses. With ultralow-dose CT, the radiologists made a correct diagnosis in 89 percent of the cases.

“X-rays are taken out of old habit, but with X-ray the cancer is detected too late. It’s therefore smart to use ultralow-dose CT to be able to detect the disease in time,” Aaløkken states.

Moreover, with X-ray images the radiologists detected fifteen times as many false positives. A false positive means that the patient is told that he is ill, even if he is as fit as a fiddle.

“False positives are a burden on the patient. They also entail unnecessary check-ups, which incur a high cost on society,” says Aaløkken, who concludes:

With an X-ray examination, there is a high likelihood that you will not have any answer as to whether you are ill, and an answer that says that you are ill even though you are healthy. Many are diagnosed too late. This is a dramatic consequence of the fact that the health services give priority to X-ray images above CT images.

Their research caused a stir at the world’s largest medical conference for radiology, RSNA, in 2012. Their academic article was nominated as one of the ten best from the conference.

“Even though our results are extremely convincing, we need to undertake a full-scale test to be absolutely certain.”

A question of economics

Before the diagnostic procedure is changed, the researchers must calculate the cost to society.

“A CT machine costs ten times more than an X-ray machine, but it is also costly to treat patients with advanced lung cancer.

Most people believe that X-ray is a quicker procedure than CT. This is not so.

“An X-ray check takes five minutes. A low-dose CT check goes almost as quickly; it takes seven minutes. On the other hand, the radiologists need two to three times longer to interpret a CT image,” Aaløkken and Martinsen underscore.

Odd Terje Brustugun, associate professor at the Department of Oncology at Oslo University Hospital and assistant professor at the Institute of Clinical Medicine, UiO, confirms that Aaløkken and Martinsen are on the right track.

“As far as I have understood, the method can be used on existing, modern CT machines. Before it can replace ordinary chest X-ray some work needs to be done in terms of the resource situation and training of radiographers and radiologists. The method should be tested on a greater number of patients and compared to other techniques on a larger scale before we can conclude how well it works,” Brustugun points out.