THIS ARTICLE/PRESS RELEASE IS PAID FOR AND PRESENTED BY NTNU Norwegian University of Science and Technology - read more

Major breakthrough in research on decompression sickness

An NTNU researcher has discovered what happens in the genes of divers with decompression sickness. The breakthrough is gaining international attention after more than a century of searching for the causes of divers’ disease.

It is infinitely beautiful below the ocean’s surface.

So beautiful that every year some divers are tempted to go a little too deep and stay there a little too long.

DCS has been a known condition for more than a century. The disease – sometimes referred to as the bends – occurs when a diver returns to the surface too fast.

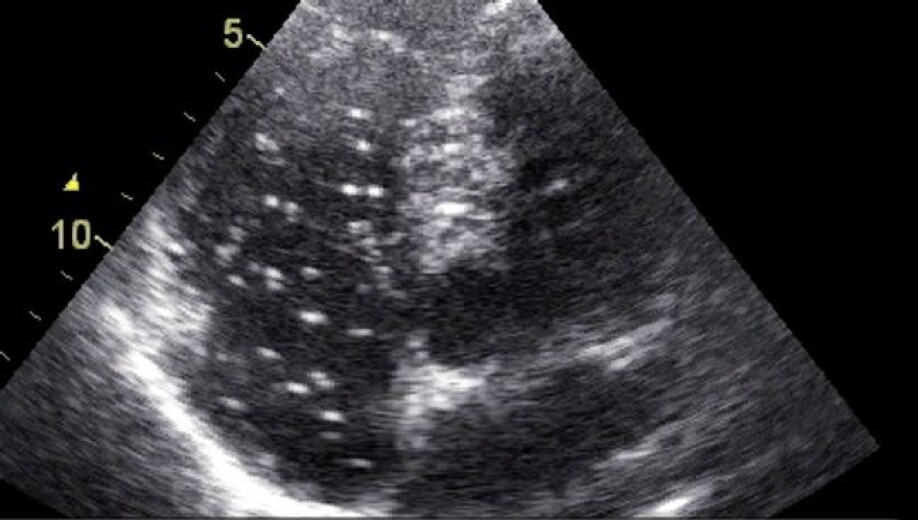

Gas bubbles form in the blood and tissues due to decreasing water pressure in the ascent. Some divers become paralyzed for life. Others get skin rashes or a little pain in their joints. The condition can be fatal.

No medical test is available that can reveal whether you have the disease or not. Until now.

The discovery is the first step in developing a blood test that can make it easier to check if someone has decompression sickness (DCS).

Strikes adventurous recreational divers

To date, diagnosis and treatment are based only on symptoms. No one really knows when the treatment is good enough.

“Decompression sickness often occurs in adventurous recreational divers,” says Ingrid Eftedal, a senior scientist at NTNU’s Department of Circulation and Medical Imaging.

She is one of Norway’s few experts on what happens to the human body under water.

Until now, researchers haven’t managed to describe in detail the biological changes that occur in DCS.

Now Eftedal and a team from Malta have made a major breakthrough.

“DCS is simply the immune system going crazy and causing an inflammatory condition in the body,” says Eftedal.

Examined genetic changes

The team’s findings have been published in Frontiers in Physiology, and their study is the first to describe all the changes in genetic activity in the blood of divers with the condition.

A major finding was that the white blood cell activity of the innate immune system became strongly activated. These blood cells are the first line of defence in the body’s immune system, and their activation causes inflammation in divers who are afflicted.

The finding could make it possible to develop a blood test that can diagnose the disease.

“Then we’ll be able to catch people who have a mild variant of DCS, and we’ll also be able to check when they’ve completed treatment,” says Eftedal.

Today, only a few Norwegian hospitals have solid DCS expertise. If you become ill in Trondheim, for example, you would need to be flown to Bergen to receive treatment in a pressure chamber where you breathe oxygen at high pressure.

A blood test would make it easier to make a definite diagnosis early.

Want to explore beautiful wrecks

Over the years, scuba divers have learned to reduce the risk of DCS with controlled ascents from the depths.

Very few people are diagnosed with DCS in Norway. Approximately five people each year in Central Norway receive treatment in a pressure chamber. The unreported numbers are probably much larger.

The low number means has made it difficult to study the condition. It is almost impossible to know where and when a patient is admitted with the condition, and thus equally impossible to obtain a large enough number of samples taken at the same time.

The solution lay in Malta.

High numbers of recreational divers come here every year to explore the beautiful wrecks from the country’s long history of European and Arab conquests.

The same thing happens every year: 50 to 100 divers go a little too deep, and stay there a little too long.

Doctors in Malta have a lot of experience with DCS and were very interested in collaborating with Eftedal and the research team at the University of Malta.

Measured gene expression in white blood cells

Together, the team took blood samples from divers who had been diagnosed with DCS and divers who had completed a dive without developing the condition.

The researchers took the blood samples at two different times: within eight hours after the divers came out of the water and 48 hours afterwards, when the divers with DCS had undergone treatment in a pressure chamber. They performed RNA sequencing analysis to measure changes in the gene expression in white blood cells.

The study showed that DCS activates some of the most primitive body defence mechanisms carried out by certain white blood cells.

“In the case of decompression sickness, something happens that’s reminiscent of autoimmune diseases such as arthritis. The immune system misunderstands. It’s conceivable that future treatment could also involve immunoregulatory drugs,” says Eftedal.

An earlier survey by Eftedal of healthy, experienced divers who regularly do recreational diving likewise showed changes in the activity of white blood cells during diving, even when the divers did not feel any discomfort or show symptoms of DCS.

References:

Kurt Magri et.al.: Acute Effects on the Human Peripheral Blood Transcriptome of Decompression Sickness Secondary to Scuba Diving. Front. Physiol., 2021.

Ingrid Eftedal et.al.: Acute and potentially persistent effects of scuba diving on the blood transcriptome of experienced divers. Physiol Genomics, 2013.

See more content from NTNU:

-

Researchers now know more about why quick clay is so unstable

-

Many mothers do not show up for postnatal check-ups

-

This woman's grave from the Viking Age excites archaeologists

-

The EU recommended a new method for making smoked salmon. But what did Norwegians think about this?

-

Ragnhild is the first to receive new cancer treatment: "I hope I can live a little longer"

-

“One in ten stroke patients experience another stroke within five years"