THIS CONTENT IS BROUGHT TO YOU BY University of Oslo - read more

Cod's immune system leaves researchers puzzled

Researchers are struggling to understand how cod can live a healthy life – for it lacks a part of the immune system that healthy humans depend on.

The immune system is vital. Researchers have therefore believed it is not as affected by evolution. Research on cod shows that it is probably more complex.

"Cod is no more sick than other fish," molecular biologist Synne Arstad Bjørnestad from the Department of Biosciences at the University of Oslo says.

She researches the immune system of cod and has recently published an article on this. She has looked at one possible explanation for how codfish manage to compensate for their immunological deficiency.

"We like to say that cod has an immunological deficiency, but it is important to specify that this statement can be made only as we compare different immune systems and use the human immune system as the 'best' solution. It is not certain that the human immune system should be the model of what a good immune system is. At least not for all vertebrates," Bjørnestad says.

Lacks genes

The cod genus lacks the gene for the part of the immune system called MHC class II and a group of other genes necessary for the function of MHC class II.

This means that MHC class II does not work in cod.

This part of the immune system defends the body against bacteria and parasites. Humans with a damaged MHC class II will become seriously ill and die, but the cod survives. This has left scientists scratching their heads.

"One explanation of how cod can make up for this deficiency is that it has expanded other parts of the immune system, including the closely related reaction pathway involving MHC class I," Bjørnestad says.

Thus began the hunt to confirm whether this is true.

Cod manages without

Codfish lack the part of the immune system called MHC class II and apparently get along just fine without it.

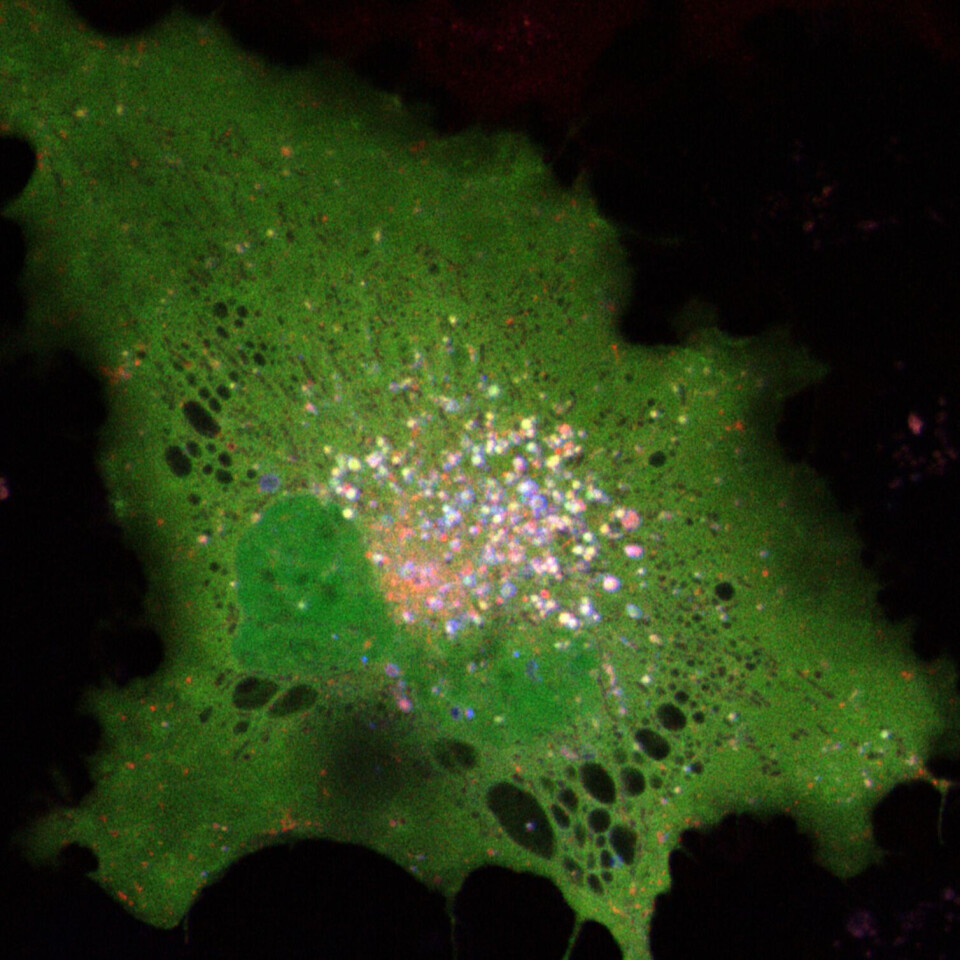

"We see that the cod has far more gene copies of MHC class I than we see in other species. One theory is that some of these gene variants of MHC class I can carry out what we call cross-presentation to a greater extent. This means that MHC class I takes over some of the role of MHC class II by binding protein fragments originating from outside the cell. Thus, some of the function of MHC class II can be compensated for," Bjørnestad says.

By analysing where the different MHC class I variants are located in cod cells, she and other researchers have demonstrated that the hypothesis of increased cross-presentation might be correct.

They find MHC class I where they would have expected to find MHC class II.

Want to understand more about the immune system

Bjørnestad sees a possible adaptation where cod, instead of using two very closely related reaction pathways, only uses one reaction pathway with an increased number and more versatile MHC class I molecules.

"MHC I and II are highly conserved gene regions in most vertebrates, but the cod family lost MHC class II around 100 million years ago," she says.

However, it is not the case that the loss of MHC class II is unique to codfish. Loss of MHC II or parts of its reaction pathway has also been documented in other species, including pipefish, seahorses and monkfish.

Cod could be important for medical research

The genes for the immune system are believed to be 'conserved' across species, meaning that there are few evolutionary changes over a long period of time.

Now it seems that this is not the case. Bjørnestad finds it interesting to understand how the immune system wprks in other species.

"It then becomes dangerous to use humans or mice as a model organism to understand how it works in other species," she says.

The notion that many immunologists and cell biologists have, that the immune system in mice and humans is the best model for all vertebrates, is wrong. It may apply to mammals, but not to fish, where many different variants of the immune system have recently been discovered.

Although this is basic research, Bjørnestad believes that the knowledge is important. The deficiency in cod could indeed make it an interesting model organism for understanding how disease in humans with defective MHC class II could possibly be overcome in the future.

Once researchers better understand the cod's immune system bet, we might be able to develop new strategies for vaccination. And who knows, maybe it will also be useful if there is another pandemic?

"Cod has an innate immune system, and here we also see big differences compared to other species. Most likely, cod uses the interplay between the innate and adaptive immune systems to a greater extent. Understanding more about this interplay is exciting. There is a lot we still don't know. Theremore, more knowledge about this is important," she says.

It may have been a 'cod pandemic' that led to the change

Bjørnestad says it is possible that a disease led to the change in the immune system.

"The reason why the cod genus may have lost MHC class II may be the result of a disease that used a receptor on white blood cells to infect the cell, much like with HIV in humans," she says.

It is possible that codfish were exposed to such a disease, and those that survived did so precisely because they were missing that part. Since that event, about 100 million years have passed, and the conclusion seems to be that the cod has managed very well without it.

"Maintaining and running an immune system is energy-intensive for an organism, so in a way, cod could benefit from this by using less energy," Bjørnestad says.

But what happens to cod when it gets sick?

When we get sick, the body will produce antibodies to the virus or bacteria that made us ill – but this is the part cod lacks.

"But what happens to the cod when it gets sick?"

"We don't really know, but it survives. MHC class I also fights disease, but in a different way than MHC class II," Bjørnestad says.

Traditionally, MHC class I cooperates with a type of T cell that eliminates pathogens in a slightly more brutal way than MHC class II does, she explains.

Bjørnestad emphasises that there are still many missing pieces in this puzzle. Even though she has now contributed to showing that MHC class I possibly takes over for parts of MHC class II, there are still many unanswered questions. But one thing is certain: Cod does not necessarily have a poor immune system even though it is different from ours.

"It's important to have a more open mind about what constitutes a good immune system," she concludes.

Reference:

Bjørnestad et al. Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) MHC I localizes to endolysosomal compartments independently of cytosolic sorting signals, Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology, vol. 11, 2023. DOI: 10.3389/fcell.2023.1050323

This content is paid for and presented by the University of Oslo

This content is created by the University of Oslo's communication staff, who use this platform to communicate science and share results from research with the public. The University of Oslo is one of more than 80 owners of ScienceNorway.no. Read more here.

More content from the University of Oslo:

-

"Fascism must be countered with knowledge"

-

Asian leaders on social media: Share stories about their love lives, offer advice on radio shows, and play with cats

-

Demonstrations: Meeting face to face may be more important than ever

-

"Everyone knows it, everyone’s seen it. Most people have a perception of nightlife chaos”

-

Music in film and TV: “It's a form of manipulation”

-

Can you take antidepressants while pregnant?