This article is produced and financed by University of Oslo - read more

Chaga: myth-enshrouded fungus may become possible future cancer treatment

In folk medicine, chaga is considered by many as a miracle cure for "everything". Although those expectations are exaggerated, the fungus may be a future basis for cancer medicine.

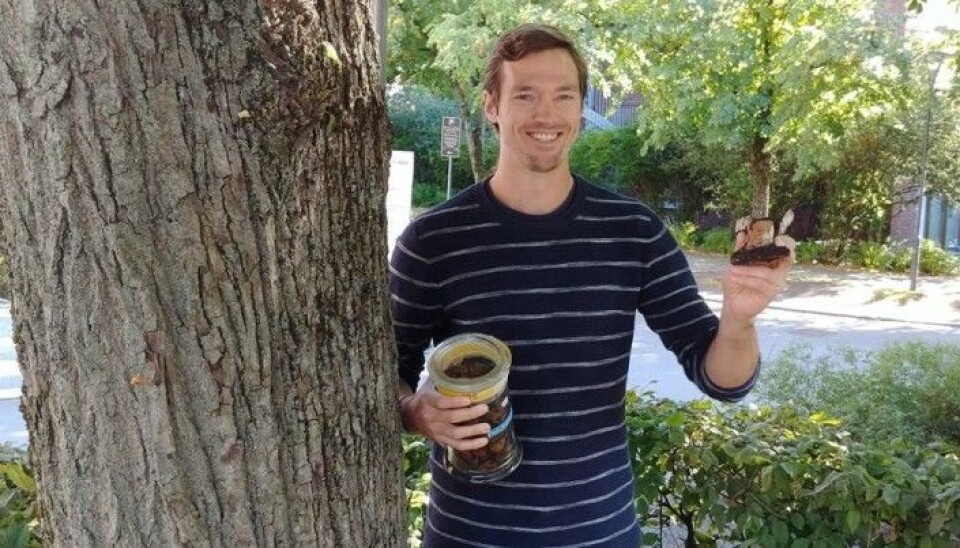

“My interest in chaga started several years ago, while I took my master's degree in Trondheim”, says Christian Winther Wold, a recent PhD from the Department of Pharmacy, University of Oslo (UiO).

“A friend told me about this fungus that was supposed to have almost unbelievable health benefits. My curiosity was piqued, so just for fun I tested a decoction of the fungus on two cell cultures I was working on at the time. One of the cultures was cancer cells, the other healthy cells.”

When Wold arrived at the lab the next day, his eyebrows were raised. The cancer cells had completely stopped growing, while the healthy ones were still alive and well. His supervisor also found it a surprising and interesting discovery, but as the master's degree was about something else, nothing more became of it at that time.

Grows on living trees

But after he had been working for several years after completing his master's degree, Wold had the chance to do more research on chaga, as a research fellow in the research group BioNatH at UiO.

“Chaga has been used as folk medicine around the world. Quite a bit of research has been conducted in countries such as Russia, China and South Korea, but even though chaga it is widespread in Norway, there is almost no research on it in this country”, says Wold.

Chaga belongs to a group of fungi called polypore fungi. Most tree-living polypore fungi live on dead wood, but chaga is among those that grow on living trees. It is mostly associated with birch, but can also grow on other species, such as alder and beech.

Sugar molecules

Although the Department had other ways of obtaining research material, Wold thought it would be great to obtain some himself. He had noticed a beautiful chaga on a birch tree in a residential area in Oslo. One dark night he took the matter, more precisely the axe, in his own hands and went chaga raiding.

“I still have a small part of the loot left, but now five years later it has become rather desiccated”, he smiles.

The challenge was to find out if chaga really contains the beneficial substances that folk medicine claims it does. A group of polysaccharides, a molecule consisting of several different sugar molecules, stood out as possible candidates.

No need to worry

“These polysaccharides are pro-inflammatory, not anti-inflammatory. Since drugs usually aim to alleviate inflammation, one might not expect polysaccharides to be of much use”, says Wold.

“But one of my supervisors, working at Rikshospitalet University Hospital in Oslo, told me that they used some pro-inflammatory drugs in pre-clinical cancer research. So we decided to investigate more closely how polysaccharides affect cancer growth.”

The results were surprising.

An important cell type in the immune system are macrophages, but cancer cells often manage to trick macrophages present in the tumour microenvironment into believing that there is no need to worry, making them remain passive.

Nobel Laureate in Literature

“Not only that: we also discovered that cancer cells actually thrive better together with macrophages than they do alone. It may look like the cancer cells are able to manipulate the immune system to help themselves”, says Wold.

“But when we added these polysaccharides, it was almost as if they revealed the scam. Suddenly the macrophages were activated and began to attack and kill the cancer cells.”

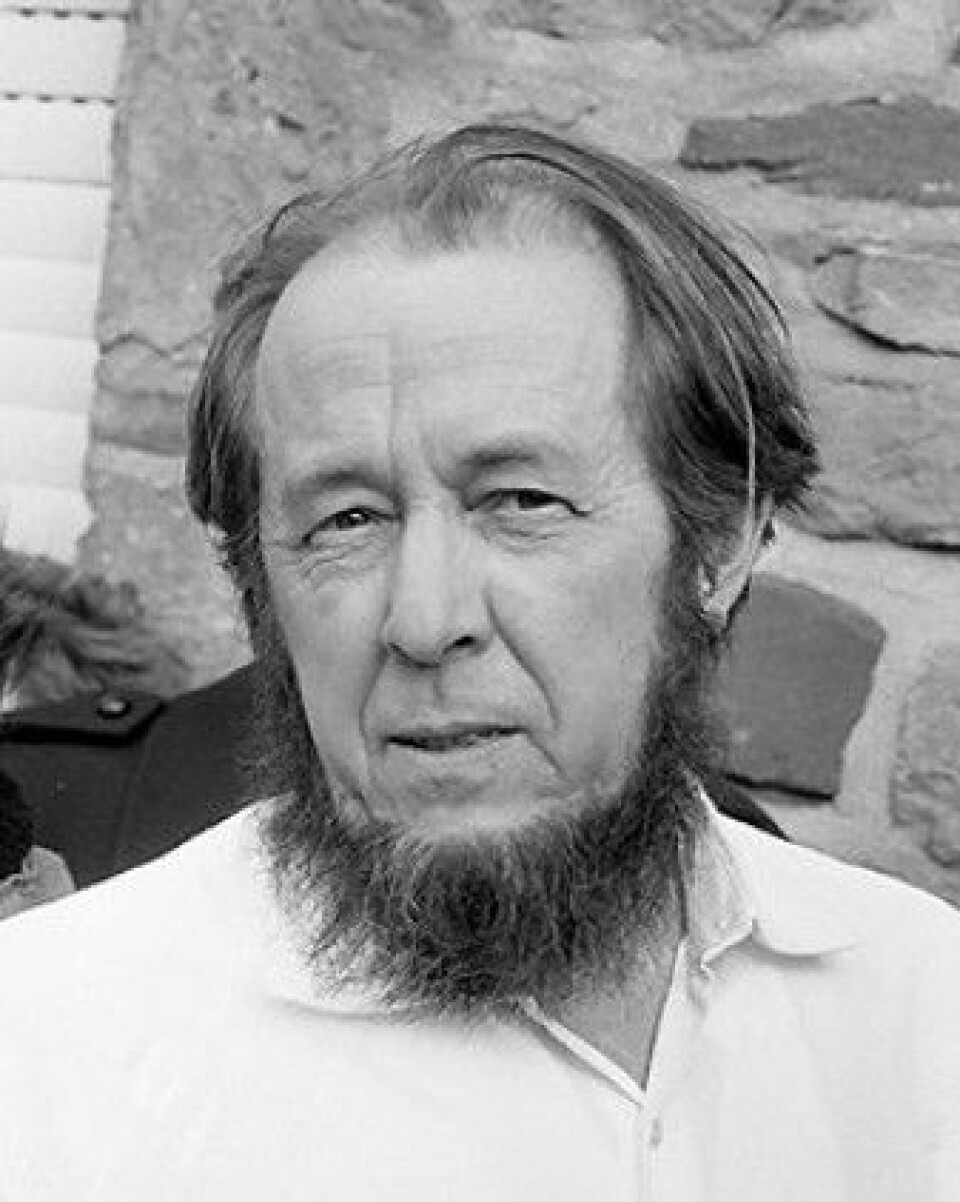

Especially in Russia, many believe that chaga helps against cancer, not least because Nobel Laureate in Literature Alexander Solzhenitsyn claimed so in his book "The Cancer Department".

Dissolves poorly in water

Wold issues words of caution:

“No one must think that the chaga extract available in health food stores will have any effect against cancer. These polysaccharides are not absorbed in the intestine to any meaningful extent, so the effect they will have there is probably only on the local immune system in the intestine.”

Betulinic acid, another compound from chaga, has been shown to be even more effective against cancer cells by killing them directly. But betulinic acid has a big disadvantage: it dissolves very poorly in water. Therefore, the body is unable to absorb much of it.

“But if we succeed in finding substances that have a similar structure to betulinic acid with improved bioavailability, they may be better suited for pharmaceutical use”, Wold says.

Same effect of all

The fact that betulinic acid dissolves poorly in water also means that there is very little of it, or of any other of the anti-carcinogenic substances from chaga, in extracts typically used in folk medicine. These preparations are mostly water-based, what pharmacists call water extracts.

Another chemical compound discovered in chaga has the not-so-simple name 3β-hydroxy-lanasta-8,24-dien-21-al. It is immunologically interesting for researchers because it activates a part of the immune system called the complement system. It also has a very special property.

“It is usually the case that when we test ten substances that are quite similar to each other, we will see the same effect from all of them, to a greater or lesser degree. Of all the substances we tested, 3β-hydroxy-lanasta-8,24-dien-21-al had the greatest effect on the complement system”, Wold explains.

Opposite effect

“So we would expect that the substances that most closely resembled 3β-hydroxy-lanasta-8,24-dien-21-al would have a similar effect, although perhaps to a lesser degree. But that is not what occured. They had no effect whatsoever. The fact that 3β-hydroxy-8,24-dien-21-al has an effect on the complement system that is so specific and so potent at the same time, makes it a promising future drug candidate.”

There is another substance, though, that may appear to allow chaga extract to partly retain the promise of folk medicine to help with stomach and intestinal ailments. This substance is a melanin pigment, but with a different structure than the pigment that gives colour to the skin and hair in humans and other animals.

“This melanin has the opposite effect of the other substances we examined in that it is anti-inflammatory. Water extracts of chaga consist of just a few percent polysaccharides, the rest is mostly melanin and other compounds with antioxidant activity”, Wold says.

Both confirm and deny

“When we know that many intestinal disorders are due to an overactive immune system, and that melanin may have the ability to suppress the immune response, it is conceivable that melanin can act against such disorders”, says Wold.

“But we cannot establish that until we have investigated in more detail how the melanin works in our body.”

Wold's research has shown that various substances from chaga with very different molecular structures can affect different parts of the immune system, and opens further pharmaceutical research paths.

The odd thing is that folk medicine beliefs in chaga as cancer medicine is both confirmed and denied: yes, chaga contains substances that have potential as cancer medicine – but even though isolated substances have potential, they are probably present in far too low concentrations in the folk medicine extracts to have any direct effect on cancers.

Referanse:

Christian Winther Wold: Immunomodulating polysaccharides, triterpenoids and melanin from the medicinal fungus Inonotus obliquus (Chaga). Doctoral dissertation from UiO, 2020. Abstract.