THIS ARTICLE/PRESS RELEASE IS PAID FOR AND PRESENTED BY University of Oslo - read more

Nastier variants of bacteria hide in your body. After a course of antibiotics they take over

A doctor discovers bacteria in a sample that is causing a case of pneumonia and prescribes antibiotics. But at the same time, there is another, nastier variant of bacteria lurking in the patient’s body. It is glad to be rid of its competitor.

All over the world, there is an increasing problem of antibiotics not working when treating certain bacteria. Some so-called multi-drug-resistant bacteria can even survive several types of antibiotics.

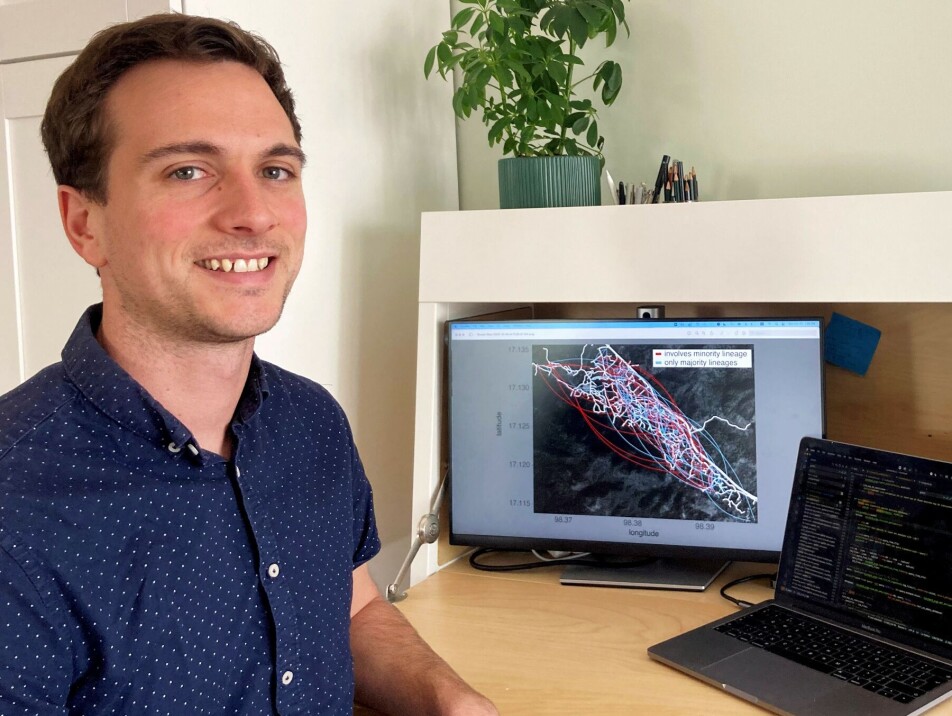

“The bacterium Streptococcus pneumoniae can cause pneumonia, meningitis and bacteraemia. Many different variants of this bacterium exist and our study reveals that you can have several variants in your body at the same time,” Gerry Tonkin-Hill says. He is a postdoctoral fellow at the Institute for Basic Medical Sciences at the University of Oslo (UiO).

Some of these variants can be multi-drug-resistant.

Competition between bacteria

These bacteria can pose a larger risk to children and the elderly, causing serious illness and even death.

“We found that those who fell ill could have other, multi-drug-resistant variants of the same bacterium hiding in their body. When the patient begins taking antibiotics to combat the first bacterium, the other multi-drug-resistant variant can then take over, since it no longer has to compete against the first one,” Tonkin-Hill explains.

The study was recently published in Nature Microbiology.

A deeper analysis of samples from patients is important

Tonkin-Hill and his collaborators recruited mothers and children in Thailand and took blood samples from them every month for a period of two years. The researchers then selected 4,000 samples that they checked for many different variants of the bacterium using a new method.

The method is based on what is termed deep sequencing. This study is likely the largest to use this method up until now.

The researchers recorded how many of the participants fell ill during the two-year period and what sort of antibiotic treatment they received. They also found that the bacterium was often transmitted from mother to child and vice versa.

“Most people have this bacterium in their body without getting ill. But if, for instance, a virus infection takes hold, pneumococci can subsequently result in a serious bacterial infection,” the postdoctoral fellow says.

Every year, 300,000 children throughout the world die due to illness caused by the pneumococcus bacterium.

Tonkin-Hill says the study‘s findings will play an important role when it comes to developing good methods of treatment for the future. One improvement will be to carry out a deeper analysis of patient samples.

“There is a higher risk of serious illness in children if they are infected by multi-drug-resistant bacteria before they are vaccinated. Since our study has shown that several variants can be present in the body at the same time, it may be necessary to consider more carefully which antibiotic to use and to monitor the child further after treatment has been given,” he believes.

In addition, Tonkin-Hill advocates better monitoring so that any spread of the most harmful bacteria is quickly contained.

A vaccinate cannot solve everything

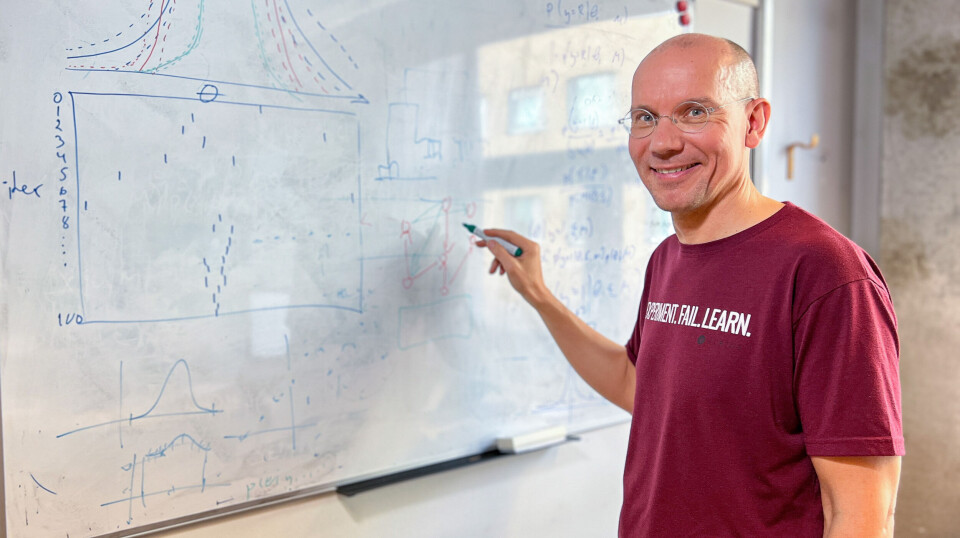

Professor Jukka Corander at the Department of Biostatistics, says that vaccines against pneumonia are not a full-proof solution to this problem.

“We currently have a vaccine to combat 13 types of these bacteria and new vaccines are in the pipeline which should protect against 20 others. But over 100 types already exist. They develop fast, which means that there are ever new variants that can result in serious illness,” he says.

Rapid tests and tailored treatments

According to the professor, there are two things that are especially important if we are to win the battle against these bacteria.

“One is that we must find quicker ways of making a diagnosis and of analysing blood samples in greater detail in order to find all the variants that are present in the patient’s blood," he says.

At present, it can take between one to three days to get an answer on the resistance factors relating to a bacterium.

"In the future, I hope that rapid diagnosis will be the norm. Work is being carried out on this in several places, for example at Haukeland Hospital in Bergen. The aim is to be able to get an answer within one to three hours," he says.

The other aspect that Corander believes to be important is the ability to tailor treatments more in the future. This means carefully checking which variant of the bacterium is making the patient ill and administering a narrow-spectrum medicine that has been developed to combat that very variant.

“Several pilot projects for this are underway, for instance at Oslo University Hospital, Rikshospitalet and Ullevål,” he reveals.

Corander adds that in Norway, we are lucky in that the incidence of multi-drug-resistant bacteria is currently low. But we must continually strive to prevent multi-drug-resistance becoming a growing threat in the future, he argues.

Reference:

Tonkin-Hill et al. Pneumococcal within-host diversity during colonization, transmission and treatment, Nature Microbiology, vol. 7, 2022. DOI: 10.1038/s41564-022-01238-1

This article/press release is paid for and presented by the University of Oslo

This content is created by the University of Oslo's communication staff, who use this platform to communicate science and share results from research with the public. The University of Oslo is one of more than 80 owners of ScienceNorway.no. Read more here.

See more content from the University of Oslo:

-

Where humans outshine AI: “There's something hopeful in these findings”

-

Why we need a national space weather forecast

-

Mainland Europe’s largest glacier may be halved by 2100

-

AI makes fake news more credible

-

What do our brains learn from surprises?

-

"A photograph is not automatically either true or false. It's a rhetorical device"