THIS ARTICLE/PRESS RELEASE IS PAID FOR AND PRESENTED BY University of Oslo - read more

In Soviet society, freedom of speech was never on offer

When Soviet artists omitted significant words or images from their work, this could both be an allusion to and a play on the lack of freedom of speech.

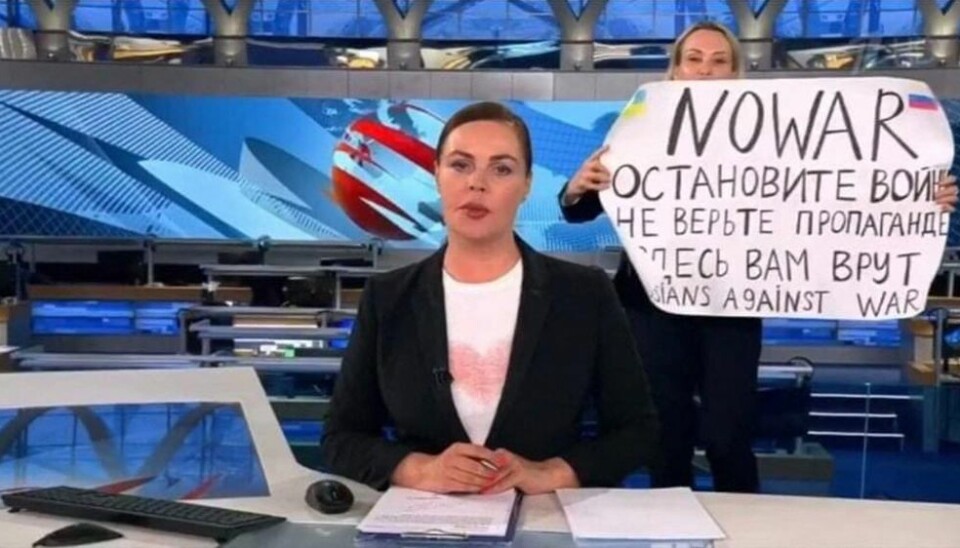

Russia, March 2022: The cover of the independent Russian newspaper Novaya Gazeta shows the image of the woman who got attention worldwide when she stormed a news broadcast on Channel 1, holding a poster with an anti-war message and shouting anti-war slogans.

But one thing is missing from the picture on the magazine cover. The word “war” has been deleted.

In today's Russia it is not allowed to use the word “war” in connection with the invasion of Ukraine.

Shortly after this incident, videos showing a scene of young people being arrested for silently and peacefully holding up blank posters to protest against the war spread on social media.

“Both actions have one thing in common: they make use of techniques of self-censorship to express or thematise protest despite state restrictions. Both actions try to exhaust how far they can go and challenge imposed boundaries.”

This is how Vera Faber, a literature researcher at the University of Oslo with Ukrainian art and literature as her field of expertise, explains the strategies used by the journalists of Novaya Gazeta and the young Russian protesters in Moscow.

This way of challenging the boundaries of political constraints is not new.

Soviet citizens, and not least Soviet writers and artists, have balanced between censorship, self-censorship, and subversive counter-action during many historical periods.

“It is about freedom of speech, in a society where free speech is not allowed,” Faber points out.

В эфире программы «Время» за спиной ведущей Екатерины Андреевой появилась девушка с плакатом, содержание которого нам запрещают передать Роскомнадзор и Уголовный кодекс.

— Новая Газета (@novaya_gazeta) March 14, 2022

По неподтвержденной информации, это редактор Марина Овсянникова.

В настоящий момент она задержана. pic.twitter.com/TdpkscVpuS

Novaya Gazeta censored the word «war» and the rest of the content on the poster on Twitter as well as on the print edition of their magazine. (Screenshot: @novaya_gazeta/Twitter)

To voice the inexpressible by not saying it

In Rhetoric, an ellipsis can be explained as an abbreviated mode of expression. A meaning remains obvious, however it is not pronounced, as when three little dots indicate that a certain word, an expression, or a sentence is omitted.

When Vera Faber looks at literature, photography, and artefacts from Soviet everyday life, she finds what she interprets as such ellipses.

“The concept of the ellipsis, which I see as an intentional, purposeful and active employment of an omission, has had a long history in the Soviet Union,” she says.

Using techniques of omissions is not necessarily self-censorship, according to Faber.

“During the Soviet period, omissions were also used as creative devices both to respond to political repression and to process traumatic experiences that could not actually be expressed.”

In a repressive society, censorship and lack of freedom of speech are pervasive. During Soviet rule certain individuals and groups were marginalised, many were imprisoned, deported to Gulags or executed.

“Censorship practices included controlling what could be printed, rewriting or altering existing texts without the author's consent, destroying entire editions of existing publications, retouching people from images and film cadres, rewriting history and destroying testimonies about people and their life and work,” Faber explains.

Artistic movements were also banned.

“Artistic work was removed from the official canon; many artworks even were even destroyed, or kept under lock and key in special archives.”

Hardship and oppression throughout Ukraine’s history

Ukraine became part of the Soviet Union when it formed in 1922. Faber emphasises that many phases of the Soviet Ukraine’s culture are directly linked to repression and trauma, and in her research, she studies how artists and writers, but also everyday life, was affected by the political context.

“In the 1920s, there was a vital artistic avant-garde in Ukraine, for instance in Kharkiv, which was the capital of Soviet Ukraine at the time,” says Faber, who in her latest monograph has dealt with the ambivalent artistic positions proclaimed in this era of Ukrainian culture.

“The creative scene experimented with literature and art, and there was a clear, but at the same time ambiguous interplay between politics and art.”

At the time, there were strong tensions between Ukrainian self-determination and nation-building on the one hand, and the expectations towards the Soviet system on the other hand.

“Many Ukrainians believed in the idea of an independent Ukrainian nation; and this idea was particularly popular among artists and writers, who explicitly welcomed the communist project.”

This era would not last. The 1920’s nation building phase of the early Soviet years was superseded by Josef Stalin's project of forced industrialisation and collectivisation in the late 1920s.

“When Stalin came to power, the rooting policy, from which many had great expectations, was suspended. In the 1930s, repression increased, millions of Soviet citizens became victims of Stalin's purges, and a significant part of the Ukrainian cultural elite was executed.”

In the thirties, Ukraine was Europe's granary. Under Stalin’s rule, the grain was exported, and people in Ukraine starved.

“This resulted in a man-made famine, with millions of people dying by hunger,” Vera Faber explains.

Experimental poetry contesting boundaries

Under Stalin’s rule, artistic movements increasingly became affected by restrictions and Soviet writers were forced to limit themselves in their writing.

“At the beginning of the 1930s, many movements, including formalism and the avant-garde, were banned. As a result, they were limited and could not articulate themselves to their full extent,” Faber says.

Writers and artists responded to the difficult situation in various ways, again often using techniques of omissions to resist the constraints on freedom of speech.

“Literary texts from authors like Daniil Kharms from Russia or Maik Iohansen from Ukraine, for instance, are coined by absurdist elements – and thus by omissions on the level of meaning.”

Literary texts from this period can be challenging to read, with fragmented sentences and words missing.

“But this was only one technique. Others experimented, for example, with ignoring the imposed norms of Soviet society by explicitly alluding to the obscene in their texts. This was a way to contest imposed invisibility.”

Leaving technology out of Chernobyl’s history

The impossibility to speak due to repression and traumatic experiences has affected entire generations.

The late 1950s and the early 1960s brought a more liberal phase.

“The society started to talk about and work on their own history and the events of repression. But this phase did not last long, and unfreedom of speech continued,” Faber says, and continues:

“From the 1960s on, literature that did not conform to the norms of Socialist Realism did not receive permission for publication, so it had to be ‘self-published’. Intellectuals and those designated political opponents could still become political prisoners.”

In texts from later phases of the Soviet period, Faber has identified creative strategies also using the ellipsis, but here it is applied in the narrative structure.

“The Chernobyl disaster in 1986 occurred in the context of the Soviet belief in technological superiority. However, literary reflections written in the years following the disaster largely omit references to technological progress.”

One example is a series of short novels by the Ukrainian author Yevhen Hutsalo, dealing with the everyday village life in the immediate vicinity of the Chernobyl reactor.

“Signs of technical progress appear to a limited extent, but they have consistently negative connotations. Thus, we get to know the idyllic life in the villages, encounter personified cows, dogs and insects, and we sense that the people are confronted with an intangible threat,” Faber explains.

“But there is no explicit reference to the catastrophe that must not or cannot be spoken about.”

Ukraine remains invisible in international literature and art

Against the background of the current war on Ukraine, research on Ukrainian culture is more important than ever, Faber believes.

“Traditionally, there has been a clear focus on the Russian 'centre' of the Soviet Empire while much less attention has been paid to the Soviet 'peripheries'. Consequently, yet still today there are many gaps in the knowledge about and the research on the non-Russian Soviet and Post-Soviet societies,” she says.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, it became possible to document more of Ukrainian culture and to reconstruct and preserve historical evidence. Archives were opened and researchers gained access to large amounts of material to work with.

Consequently, in the last years the editions of Ukrainian literature and the research on Ukrainian culture reached a peak, in particular inside of Ukraine. Ukrainian authors have also been translated into many languages.

“In recent years, Ukrainian culture has thus become more visible on an international level and knowledge not only about Ukrainian culture but also about Soviet culture has increased enormously.”

The war could put an end to these positive developments.

“Now many of the archives and many of the testimonies of Ukrainian cultural heritage are being destroyed. In fact, in addition to the humanitarian catastrophe of the war, the country is experiencing a cultural heritage disaster,” Faber says.

See more content from the University of Oslo:

-

Where humans outshine AI: “There's something hopeful in these findings”

-

Why we need a national space weather forecast

-

Mainland Europe’s largest glacier may be halved by 2100

-

AI makes fake news more credible

-

What do our brains learn from surprises?

-

"A photograph is not automatically either true or false. It's a rhetorical device"