THIS CONTENT IS BROUGHT TO YOU BY NTNU Norwegian University of Science and Technology - read more

Rare Stone Age discovery in Norway

When archaeologists recently carried out an excavation at Vinjeøra in southern Trøndelag County, they made a surprising discovery that they had only dreamed of finding.

Archaeologist and project manager Silje Elisabeth Fretheim made a bold claim: She said she would eat her hard hat if the settlement they were excavating at Vinjeøra wasn’t a Stone Age discovery from some of the first people to settle along the Norwegian coast, around 11,500 to 10,000 years ago.

The first discoveries to make it to the surface seemed very promising — large pieces of flint that were highly reminiscent of early, pioneer settlements.

However, soon became clear that Fretheim would come closer to eating her hard hat than expected. What they had found was something else entirely and far more exciting.

The people from the East

When the excavations in Vinjeøra got under way properly, the researchers suddenly discovered artefacts that looked nothing like what would be expected from a pioneer settlement, but had completely different characteristics.

“We found small and medium-sized flint objects that we refer to as lithics and microlithics. Several had sharp edges that were so straight and parallel that they could have been made using a ruler,” Fretheim says.

She is an archaeologist at the NTNU University Museum.

“We also came across a conical lithic core and there was little doubt that we had discovered a different type of stone technology than we associate with pioneer culture,” she says.

Instead, the researchers found evidence from people who came to Finnmark from the East around 9000 BC.

Two waves of migration

Scandinavia was the area in Europe where ice lasted the longest during the last Ice Age. The Norwegian coast only became free of ice around 12,500 years ago.

Around a thousand years later, the first people arrived in what we today know as Norway and Sweden.

Skeletal analyses have previously shown that Scandinavia experienced two major waves of migration in the time after the ice had started to retreat.

The first came from the southwest. These were people who had lived in modern-day Spain and Portugal during the last Ice Age and later moved northward as the ice melted away. They were blue-eyed, but their skin was darker than today’s Scandinavians.

“They populated the entire Norwegian coast up to Finnmark in just a few centuries,” Fretheim explains.

A thousand years later, there was another major wave of migration, this time from the northeast. These were people who had travelled from areas around the Black Sea or Ukraine, heading north through Russia and Finland to the coast of Finnmark. They had lighter skin and their eye colours varied.

They had their own technique for creating stone tools, which clearly differed from the techniques used by the migrants from the south. This technique eventually took over and became dominant.

“It looks as though the two cultures met and both had something to teach the other. The people from the east brought new technology, while the people from the south knew the landscape and way of life along the coast, which must have been unknown to the people who arrived from the inland areas to the east,” Fretheim says.

It appears that the people from the east adopted the lifestyle of those who were already here. During the early centuries, they lived a nomadic life in lightweight housing structures, perhaps tents. Their food came from the sea and boats were likely key, just as they were for the pioneers from the south.

“DNA studies also show that the two groups mixed,” Fretheim says.

A very unusual find

So why is it so exciting to discover artefacts from the eastern wave of immigrants?

“While we have found lots of artefacts from southern migrants — the pioneer culture — along the outer coast of Central Norway to the south of Trondheim Fjord, there have been virtually no discoveries in that region that can be confidently traced back to the earliest migrants from the east,” Fretheim says.

One exception is a small settlement near Foldsjøen in Malvik, which was excavated in the 1980s, according to Fretheim.

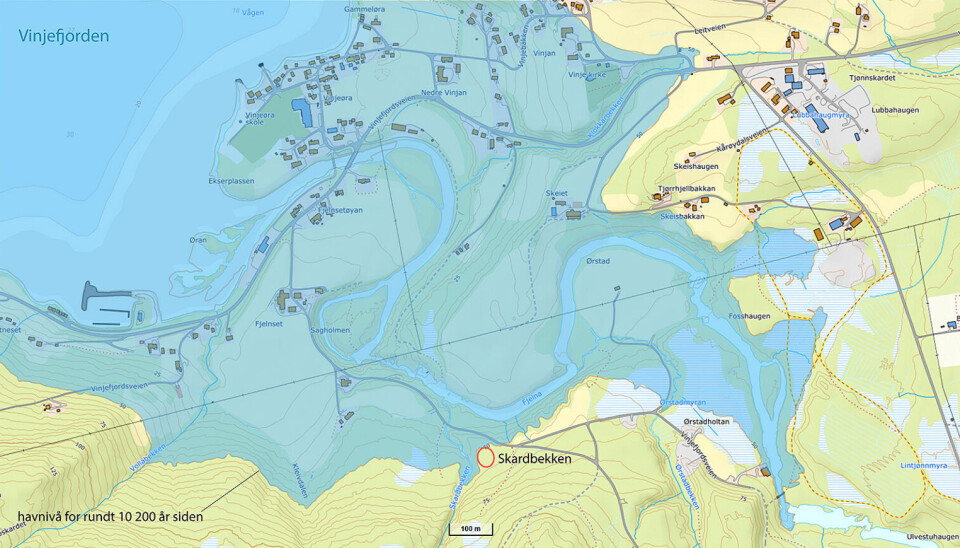

There is nothing mysterious about the lack of evidence from the eastern immigrants on the outer coast. Changes in sea level in the centuries that followed the Ice Age mean that most of the evidence of settlers along the western coast of Norway during the 8500-7000 BC period have disappeared — washed away, eroded, or buried in beach sediments.

“For this reason, there are very few discoveries from these people to be made between Finnmark and Eastern Norway,” Fretheim says. “Deep in the fjords, however, the uplift progressed differently and settlements here were consequently preserved."

However, archaeologists do not decide themselves where to dig. They have therefore not been able to focus their search on settlements from the people from the east. The reason for this is that archaeological excavations are usually carried out in connection with new infrastructure or buildings. This excavation, for example, is being carried out because the Norwegian Public Roads Administration is developing the new E39 road through Vinjeøra.

“We have dreamed of finding this for a long time and we were dealt a perfect hand here,” Fretheim says. “We are currently dating the settlement as being around 10,200 to 10,300 years old, based on the local beach displacement curve. So I have narrowly avoided having to eat my hard hat, even though the settlement turned out to be something other than what I first thought.”

More content from NTNU:

-

Fish farming is least harmful to the seabed in the north

-

Study: Centralising hospitals has reduced birth mortality

-

Early testing of schoolchildren: “We found absolutely no effect”

-

This determines whether your income level rises or falls

-

Why is nothing being done about the destruction of nature?“We hand over the data, but then it stops there"

-

Researchers now know more about why quick clay is so unstable