THIS CONTENT IS BROUGHT TO YOU BY the University of Bergen - read more

Our ancestors collected eye-catching shells 100,000 years ago. Could this be the first sign of the modern human identity?

The shells may have been used as jewellery.

A group of researchers is behind the new findings recently published in the Journal of Human Evolution. The study supports the idea of a multistep evolutionary scenario for the development of human identity.

Confirms previous scant evidence

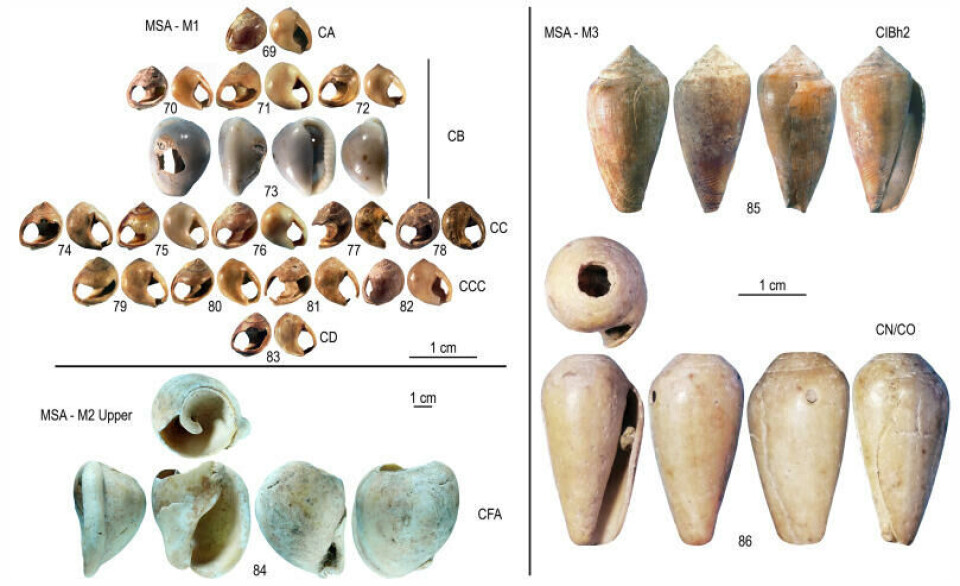

“The discovery of eye-catching unmodified shells with natural holes from 100,000 to 73,000 years ago confirms previous scant evidence that marine shells were collected, taken to the sit,e and, in some cases, perhaps worn as personal ornaments," researcher Karen Loise van Niekerk at the University of Bergen says.

She explains that this was before a stage in which shells belonging to selected species were systematically, and intentionally perforated with suitable techniques to create composite beadwork.

The shells that have been examined were found in Blombos Cabe on the southern coast of South Africa. Similar shells have also been found in North Africa, other parts of South Africa, and the Mediterranean Levant.

The significant findings provide vital information about how and when we may have started developing modern human identities.

The discovery of the unmodified shells provide evidence that marine shells were collected and possibly used as personal ornaments before the more advanced techniques to modify the shells for use in beadwork that was developed around 70,000 years ago.

Van Niekerk asserts that they are certain these shells are not remnants of edible shellfish that could have been gathered and brought to the cave as food.

Eye-catching shells made into ornaments

The shells were already dead when they were found and collected.

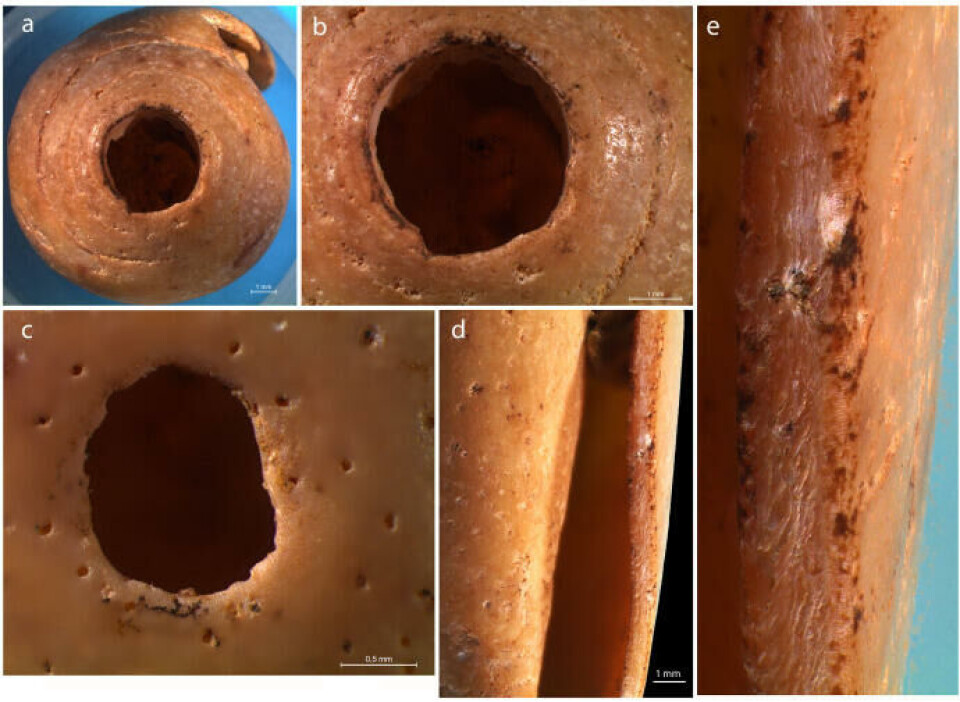

"We can see from the condition of most of the shells. They are waterworn, have growths inside them, have holes made by a natural predator, or from abrasion from wave and water movement,” van Niekerk says.

The researchers measured the size of the shells and the holes in them, as well as the wear on the edges of the holes that developed while the shells were worn on strings as jewellery by humans.

Additionally, they mapped out which shells were found together in groups and could therefore have been part of the same beadwork.

Early signs of identity formation

van Niekerk says that they identified 18 new marine snail shells from 100,000 to 70,000 years ago. They could have been used for symbolic purposes.

She also believes that the findings support the idea that there has been a long and gradual progression in how people have expressed their culture and belonging through personal adornment.

“With this study, we specifically show that humans gradually complexified practices of modifying their appearance and transformed themselves into tools for communication and storage of information," van Niekerk says.

The researchers also believe that they can observe an early creation of identity that gradually, but radically, changed the way we look at ourselves and others, and the nature of our societies.

Reference:

d'Errico et al. New Blombos Cave evidence supports a multistep evolutionary scenario for the culturalization of the human body, Journal of Human Evolution, vol. 184, 2023. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2023.103438

This content is paid for and presented by the University of Bergen

This content is created by the University of Bergen's communication staff, who use this platform to communicate science and share results from research with the public. The University of Bergen is one of more than 80 owners of ScienceNorway.no. Read more here.

More content from the University of Bergen:

-

Researchers are hoping for bad weather – so they can fly straight into the storm

-

The ice on Greenland is acting strangely. Researchers believe they finally know why

-

Early human innovation: Was climate really the cause?

-

The proteins in your blood can reveal early signs of heart problems

-

Electricity against depression: This may affect who benefits from the treatment

-

Quantum physics may hold the key to detecting cancer early