THIS ARTICLE/PRESS RELEASE IS PAID FOR AND PRESENTED BY NIKU - Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research - read more

Promising results with ground-penetrating radar in Iceland

This summer, Norwegian archaeologists have carried out several surveys using ground penetrating radar in Iceland. Preliminary results show that the investigations have already been very successful.

“The surveys have given us two clear answers: The radar signal easily penetrates through several meters of sand and ash,” says Manuel Gabler from Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage (NIKU). He is head off the geophysical survey in the field. “Furthermore, the geophysical results show a clear contrast between peat and the surrounding soil.”

“This is good news for Icelandic archaeology and suggests that there is a possibility for new and exciting discoveries in the coming years,” adds project leader Knut Paasche.

Surveys at known archaeological sites

“It will take time to process and analyse all the data, and it is therefore too early to come out with any final results,” says Gabler. Nevertheless, the archaeologists can already see that this summer’s investigations have already borne fruit.

The geophysical surveys have been carried out at well-known archaeological sites such as the monasteries at Skriðuklaustur, Kirkjubæjarklaustur and Þingeyrar, and the Viking Age farms Keldur and Glaumbær.

NIKU will continue to work with the material together with their Icelandic partners throughout the autumn and winter.

Different geological and archaeological conditions in Iceland

Conducting a ground-penetrating radar survey in Iceland is not the same as doing it in Norway. Soil and geology are different.

“Iceland is a volcanic island where much of the ground consists of ash and volcanic rocks. In addition, soil erosion has caused thick layers of sand to accumulate over and cover the archaeological finds in many areas, especially in the south of the island,” explains Paasche.

What little forest there was in Iceland was primarily birch, and much of that quickly disappeared after the island was populated in the 8th and 9th centuries. The absence of wood meant that peat became the most important building material. Buildings were constructed using peat right up until the 1950s.

NIKU archaeologists were interested to find out if these turf walls could be revealed using geophysical methods.

Promising results

NIKU archaeologists were given the opportunity to find out at the famous chieftain’s farm Keldur in southern Iceland.

Geophysical surveys were carried out here, in collaboration with the National Museum of Iceland (Þjóðdminjasafn Íslands) and architect Guðmundur Lúther Hafsteinsson.

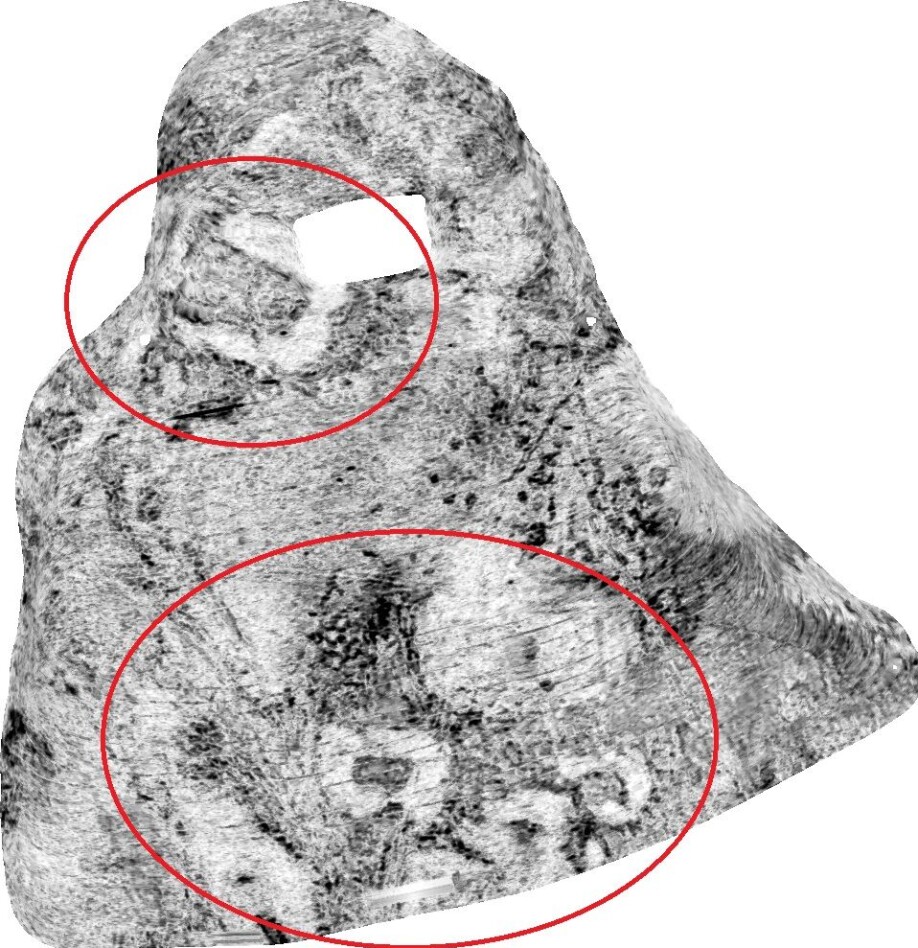

The results revealed the foundations of several turf-built houses on the land below today’s farmyard. These houses date to the Viking and medieval period.

Keldur – an important farm mentioned in the sagas

The Icelandic archaeologist Ragnheiður Traustadóttir from the archeology company Antikva introduces us to Keldur’s history:

The farm Keldur is located in a landscape dominated by the Hekla volcano. The surroundings consist of a mighty lava field and black sand.

The name Keldur means ‘springs’ and refers to numerous springs and the river that flows on the south side of the farm. Here is also the location of Iceland’s oldest preserved longhouse, dating back to the 11th century.

The fact that it has survived to this day is largely thanks to a farmer who lived on the farm at the beginning of the 20th century, who had a particular interest in history.

“Keldur is a historic place that appears in many literary sources. According to Njáls saga, Ingjaldur Höskuldsson lived here. He became famous for his betrayal of Flosi Þórðarson when he burned Njál and his sons inside Bergþórshvoll,” Traustadóttir says. “In Torlak’s saga, it is said that Jón Loftsson, Snorri Sturluson’s stepfather, wanted to establish a monastery on the farm when he lived there 1193-1197."

"Further geophysical investigation could shed light over the theory that this is the location of the monastery mentioned in the saga,” adds Paasche.

In the 12th and 13th centuries, which in Iceland is called the Sturlunga era, Keldur belonged to one of the country’s five chief clans, Oddaverjar, who were constantly at war with the other clans.

Before the battle of Örlygsstaðir in 1238, where all the most powerful families clashed, Keldur was subjected to a plundering raid. Around 100 warriors took all weapons and horses on the farm.

Can’t wait to see the results

Guðmundur Lúther Hafsteinsson at the National Museum of Iceland is very excited by the new research. He is looking forward to delving further into this material together with Icelandic and Norwegian colleagues.

This provides completely new opportunities to explore further into Keldur’s – and Iceland’s – history.

Ground-penetrating radar system In the background you can see the still standing peat houses on the farm, which have a thousand-year history. Preliminary results show the remains of several older turf houses below ground. (Video: Knut Paasche / NIKU)

This article/press release is paid for and presented by NIKU - Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research

This content is created by NIKU's communication staff, who use this platform to communicate science and share results from research with the public. NIKU is one of more than 80 owners of ScienceNorway.no. Read more here.

See more content from NIKU:

-

How shared labour keeps these old herding practices alive

-

Archaeologists debunk period myths from the Middle Ages

-

Archaeologists have uncovered a long-lost medieval market town at Hamar

-

Swedish King Charles XII transported massive ships overland to attack a Norwegian fortress. Researchers have now uncovered the forgotten route

-

According to an Old Norse saga, a man was thrown into a well in 1197 to poison the water. Researchers can now reveal more about who he was

-

This robot is on the hunt for Norway's hidden cultural heritage