An article produced and financed by NIKU - Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research - read more

The Gjellestad burial mound belonged to the Iron Age elite

Recent geoarchaeological and geophysical analysis show that the construction of the Gjellestad ship mound was carefully planned and executed.

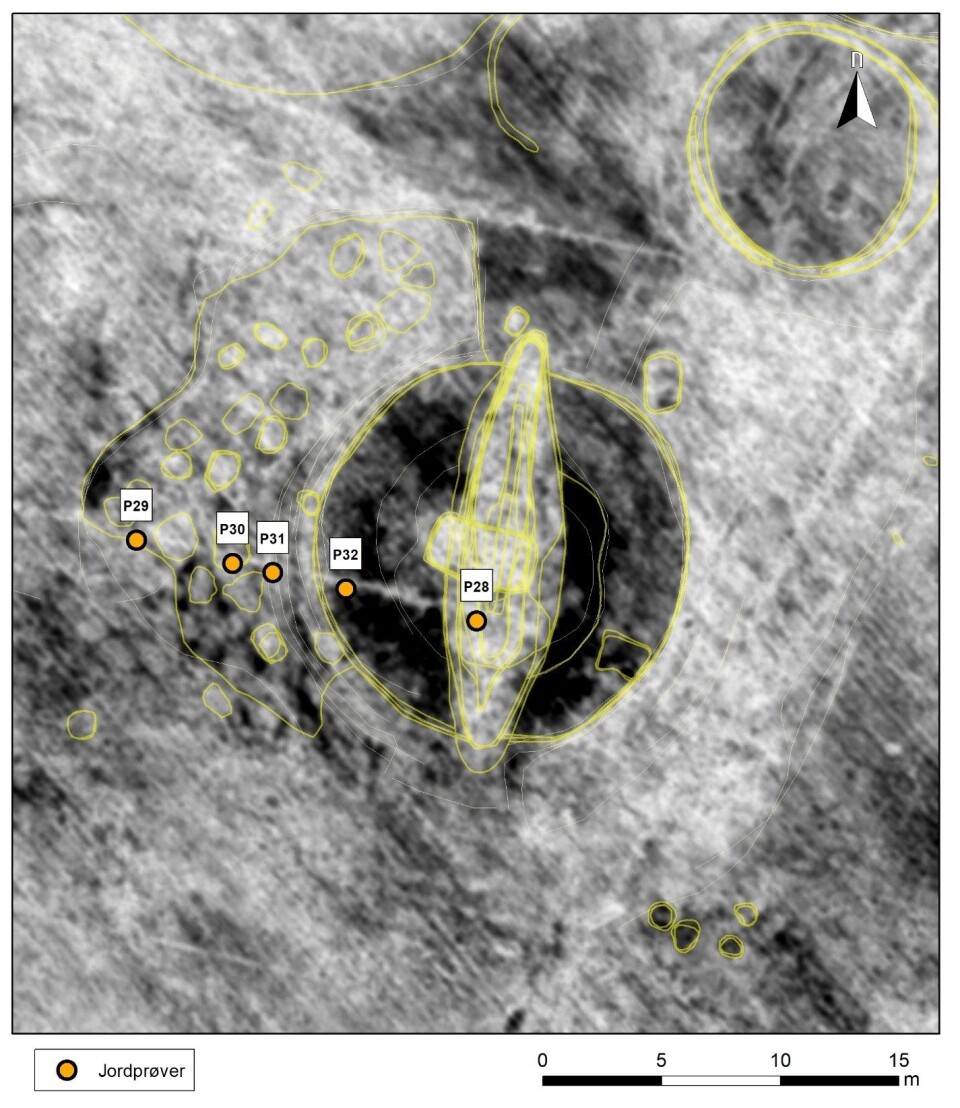

Five soil samples from the burial mound have been analyzed by researchers from the Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research (NIKU) and the University of Oslo. These were taken during excavations done by the Museum of Cultural History during autumn of 2019.

One of these samples was taken from the ship grave itself, from within the layer of soil inside the ship. The other samples were taken from the remnants of the mound that surrounded the ship.

The purpose of the analyses was to determine if these were able to reveal anything about what is visible in the 2018 dataset from the ground-penetrating radar (GPR) examinations, and if this could provide more information about how the mound was constructed.

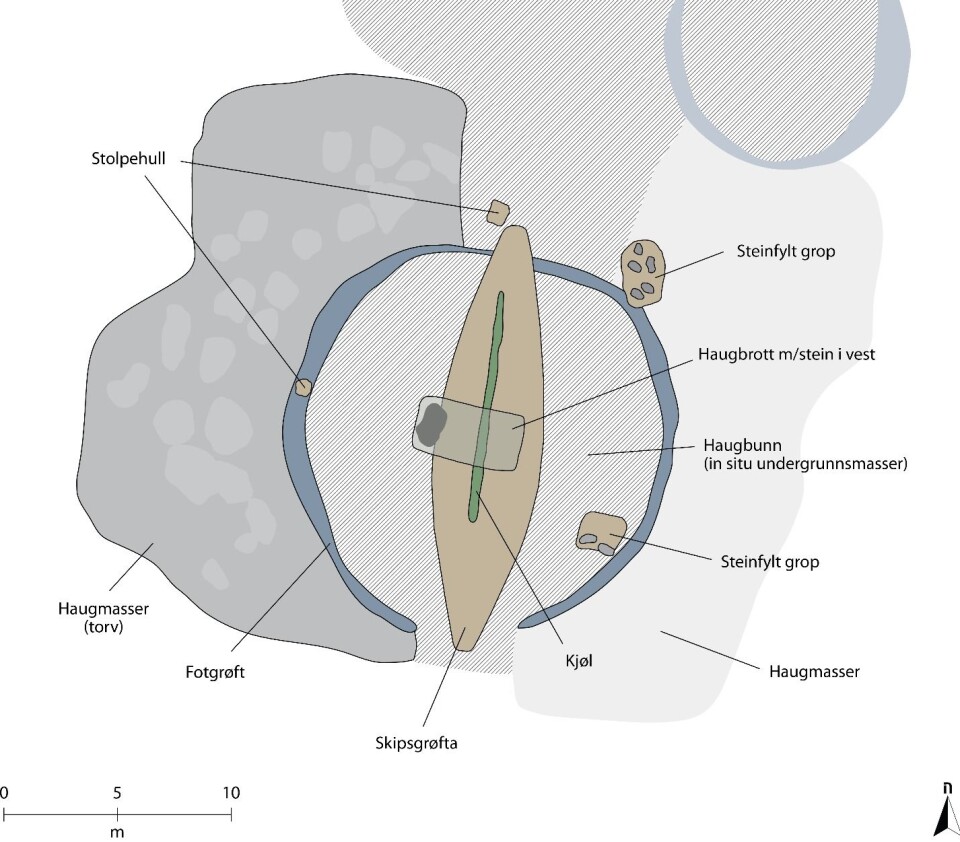

The analyses show that the construction and use of the mound is carefully planned and executed. It wasn’t simply placing the ship with the deceased on land and shoveling soil over it, according to NIKU researcher and archaeologist Lars Gustavsen.

“Here, the area of the mound has been carefully prepared by removing topsoil so that the intact subsoil was exposed. It is this subsoil that we see in the GPR data as a distinct black area around the grave itself.”

“Our analysis shows that this is soil that has been formed on-site; and the characteristic dataset signature must therefore be due to the fact that the mound covering the grave has changed the physical properties of the soil - likely due to soil compression from the heavy mound” Gustavsen continues.

Traces of rituals

Once the ship with the deceased and their grave goods was in place, researchers believe that ritual actions were likely performed before the mound was sealed.

“In the area outside of the ship we are able to discern structures that we interpret as stone-filled pits and postholes. It is difficult to interpret these structures as purely functional,” Gustavsen says.

“But since we are familiar with such actions connected to other ship graves, both from excavations and written sources, it is very tempting to place these structures in the context of such rituals,” he continues.

Soil that tells a story

The researchers have completed the soil analysis using relatively simple and well-known tools of natural science.

“We have a geoarchaeologist involved in the project, with expertise in soil analysis. In addition to conducting visual observations in the field, she has used something called a ‘loss on ignition’ analysis. This involves heating a sample to 450° so that organic material is lost. By weighing the sample before and after heating, it is possible to calculate how much organic material the sample originally contained.”

The researchers have also used something called laser diffraction particle size analysis, in order to analyze the particle sizes and relations between these. This makes it possible to learn more about the ground characteristics and tellsa us something about how and where the soil was formed.

“In all, this has enabled us to interpret the layers we have observed inside the grave mound. We are able to tell how these have been created, and how they have been affected by biological, physical and chemical processes as well as human activity,” Gustavsen says.

(Related: Why archaeologists call for an immediate Gjellestad Viking ship dig)

(Related: The viking ship at Gjellestad comes to life online)

The turf within the Gjellestad mound was from a different location

Analysis shows the mound material consisted of turf or sod, which is also common in larger burial mounds such as the Jell Mound, which was investigated in the late 1960s.

“It is unusual that we are able to prove that the turf in the Gjellestad mound couldn’t have been formed in the area, but that it must have been brought from somewhere else.”

All the signs point to the construction of this mound as being demanding on both time and resources.

“Due to similar complexity observed in the more well-known ship burial mounds and in many of the larger mounds that have been investigated, we are able to conclude that the rules for constructing these mounds were familiar and important for communities that entombed their members in this fashion,” Gustavsen says.

Hoping for further answers

The researchers have been unable to determine whether The Gjellestad Ship was laid down in a pre-existing burial mound. They also wonder if the mound was a new construction within an existing, older burial ground, or if the entire burial ground was built in just a few generations.

This will only be possible to conclude with further investigations of the burial grounds.

“If the mound was added as a new construction within an existing burial ground, we may be able to imagine a situation wherein a family from the upper social strata wishes to ally themselves with a pre-existing structure of power, in order to consolidate their own position within the social and political landscape,” Gustavsen says.

This same scenario could apply if the ship was placed in a pre-existing mound, but in that case an interpretation could be of family status being marked by an act of aggression, the researchers say.

“Either way, we are able to ascertain that the Gjellestad mound and the surrounding complex belongs to an elite stratum of the Iron Age,” Gustavsen continues.

“It will be exciting to see what the results of the museum investigations will be. We hope to be able to conduct more GPR investigations nearby so that the Gjellestad complex can be set in a larger landscape context,” Gustavsen says.

Reference:

The GPR investigations were conducted by archaeologists Lars Gustavsen and Erich Nau, while the soil analyses were conducted by geoarchaeologist Rebecca Cannell.

Lars Gustavsen mfl: Geofysiske og geoarkeologiske analyser av skipshaugen på Gjellestad. NIKU Oppdragsrapport 61/2020. DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.24253.28640/1