THIS ARTICLE/PRESS RELEASE IS PAID FOR AND PRESENTED BY the Norwegian University of Life Sciences (NMBU) - read more

From the brink of extinction: The wolverine’s comeback in Scandinavia

50 years after their near-extinction, and despite a successful return, the wolverine population is still heavily influenced by the past.

The world is getting more cramped. The traditional picture of wilderness, where nature is untouched by humans, no longer applies to our planet. Wildlife populations live in landscapes that are increasingly used and modified by humans, and these species now have to share the same space as us. The Scandinavian wolverine population is a prime example.

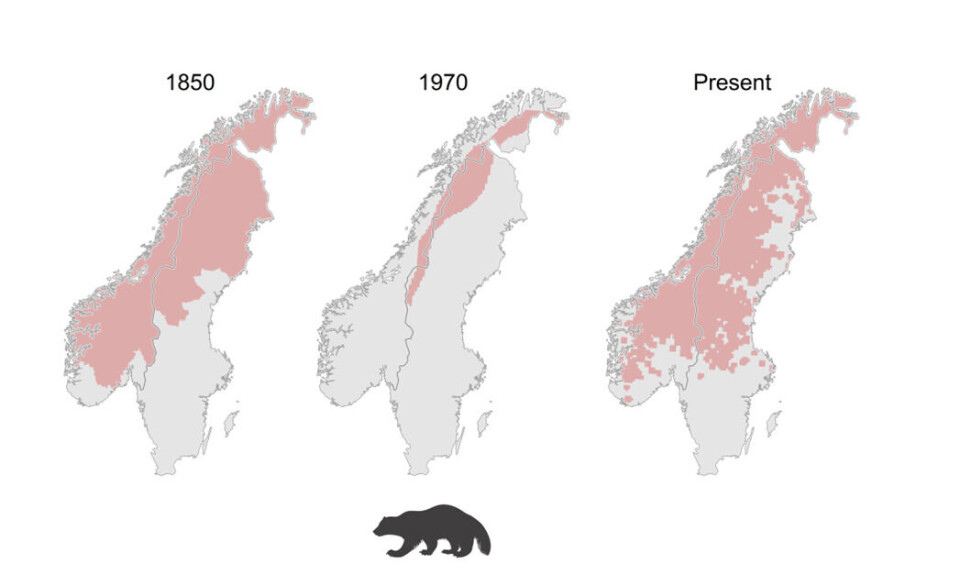

The wolverine was historically distributed throughout most of the Scandinavian Peninsula. During the 19th and 20th centuries, intensive persecution reduced its range and population size drastically.

By 1970, the population was almost extinct in many areas.

However, there was one exception: A narrow strip in the alpine region along the border between Sweden and Norway. Here, in the most rugged and inaccessible landscape, the wolverine survived in low numbers.

From persecution to protection

The tide changed in the mid-70s when national policies in Norway and Sweden shifted from persecution to protection.

“Today, the Scandinavian wolverine population has reclaimed large parts of its historical range. But, of course, the return entails new challenges," Ehsan Moqanaki says.

He is a PhD candidate at the Norwegian University of Life Sciences (NMBU).

The wolverine is a large carnivore species that needs vast areas and food resources. As opposed to historical times, the wolverine is now occupying a landscape suffused with humans, livestock, and infrastructure.

Wolverines are now recolonising areas with free-ranging sheep and reindeer husbandry, where wolverines have been absent for decades.

Their return, and the fact that they prey on livestock, has caused conflict with humans.

Traces of the past

During his research, Moqanaki found that one of the main drivers of the current wolverine population size and distribution in Scandinavia is distance from the relic range - the borderland in the mountains, where the last wolverines survived human persecution before their legal protection in the 1970s.

Wolverine density declines sharply by distance from this relic range. However, it seems that the negative impact of being far from the relic range has been diminishing over the past decade, as wolverines are successfully recolonising areas farther away from this range.

Moqanaki’s research also identified other important factors: Area covered by human settlements, prey presence and density, snow conditions, terrain ruggedness, forest cover, and so on.

“Nonetheless, 50 years later, and despite its potential for recolonisation, the long history of persecution still heavily affects the population,” he says.

Differences between regions

Regional differences in management and environmental conditions also played important roles in shaping the present-day wolverine population.

There are differences between countries. Norway is not a member of the European Union, and therefore not bound by the same set of regulations.

Wolverines are therefore subject to persistent lethal control in Norway to reduce conflict, while they are strictly protected in the EU member state Sweden, where only small hunting quotas are allowed for damage control purposes.

“We found evidence of slower recolonisation in areas that had set lower wolverine population goals in terms of the desired number of annual reproductions,” Moqanaki says.

Today’s wolverine population in Scandinavia continues to be shaped by human interests.

Expanding into new habitat

Whether it was the wolverine's preference, or low accessibility to humans that made the mountains the last refuge, is unclear.

“This relic range might be a highly suitable habitat for the wolverine. Or the animals perservered in these remote alpine areas when the persecution peaked. We simply do not know,” Moqanaki says.

Our knowledge of the wolverine’s ecology keeps expanding.

“We are now observing a shift in wolverine numbers from alpine areas into the forest,” he says.

In the past, Scandinavian wolverines were not considered to be a forest-dwelling species, as they appeared to select open and rugged terrain at higher elevations with a lot of snow, away from humans.

In recent years, however, the Scandinavian wolverine population has expanded considerably into the boreal forest and has recolonised areas without persistent snow cover. Boreal forests are full of deciduous trees and conifers.

The effects of past and present conditions

Moqanaki has examined how the wolverine population across the Scandinavian Peninsula is affected by past and present conditions.

“Not only from a scientific point of view, but also from a management perspective, this is an important question. What is shaping the population? Official management measures? Landscape features? Or history of local extinction?” Moqanaki says. “Without knowledge about the wildlife populations we manage, we risk putting resources into measures that will not work in the long run.”

Moqanaki’s research is the first attempt to investigate the factors that are influencing the population size of the wolverine across its entire geographic range in Norway and Sweden.

“It makes little biological sense to limit the study of such wide-ranging species by current political borders. Animals on both sides of the border are part of the same population,” he says.

Comprehensive database of carnivores

Norway and Sweden have established a coordinated monitoring programme to assess the status of large carnivores in the Scandinavian Peninsula.

Management authorities and thousands of volunteers in both countries annually contribute to the monitoring of large carnivores – primarily through the collection of faeces, hair, and other sources of DNA.

The resulting information is stored in a multinational comprehensive database known as Rovbase, which is globally unique in terms of the size of the area it covers, and the number of samples collected and genetically analysed.

Moqanaki’s work includes both computer simulations and statistical analyses of the large carnivore monitoring data. He has used genetic monitoring data of wolverines from this database to study their population size and important features of the landscape for the species' recovery.

“Many animals use and move between territories of both countries. Therefore, it is important that Norway and Sweden continue the amazing job of monitoring the population jointly beyond the borders,” he says.

Where and when?

In his research, Moqanaki has focused on a fundamental question in wildlife ecology and management: How many of a given species live in a given area and how are they distributed in relation to certain features of the area, such as habitat, infrastructure, and regional management?

“My main goal was to provide numbers for animals that we rarely manage to see,” he says. “Without knowing where, how many, when, and how, we cannot make informed management decisions. Although my work was largely motivated by questions raised during the large carnivore monitoring program in Norway and Sweden, the methodology and findings can be transferred to other places."

Human impact will increase

Scandinavian wolverines have recovered from the brink of extinction and are now occupying a considerable portion of their historical range.

The effects of past impacts are nonetheless still clearly visible today, modulated, but not masked, by current environmental conditions and management regimes.

“In an increasingly human-dominated landscape, the impact of humans on wolverines is likely to be even greater in the coming decades, further defining the state of the Scandinavian wolverine population,” Moqanaki concludes.

References:

Ehsan Mohammadi Moqanaki. 'Landscape-scale determinants and dynamics of large carnivore density', Doctoral dissertation at the Norwegian University of Life Science, 2023. (The dissertation)

Moqanaki et al. Wolverine density distribution reflects past persecution and current management in Scandinavia, bioRxiv, 2022.

See more content from NMBU:

-

Shopping centres contribute to better health and quality of life

-

We're eating more cashew nuts – and the consequences are serious

-

Do young people with immigrant parents have better health?

-

Who’s picking your strawberries this summer?

-

Can coffee grounds and eggshells be turned into fuel?

-

Rising housing costs fuel inequality in Norway